'2016 was the age of convenience for Hindi movies; of down pat effrontery and planned feeling triumphing over attempts to discern something complexly beautiful,' says Sreehari Nair.

And then came the fall.

Hindi movies of 2016 belonged less to the family of blockbusters, and more to the community of wham-bam bestsellers.

If you've plowed through them in the course of train journeys or even flipped through them at counters, you'd know that bestsellers are fraught with certain characteristics: Every noun invariably reaches out to the most easily available adjective; a slew of alliterations distract you when insight runs out; there's a movement toward a very definite sort of closure; and in their sentence constructions, they conform to the breath amazingly well.

Inoffensive in their composition, most bestsellers by nature, demand less from the reader; even when these books are 'courageous,' the courage stays as a pin on their lapel.

What the best Hindi movies of 2015 had in common with the truly great books was a willingness to trade easy descriptions for curiosity.

2015 was so stimulating, because a good many Hindi movies from the year had displayed the audacity to be about many things at once.

What one sorely missed this year was a picture like Badlapur, which was constructed entirely out of the swarming consciousness of a movie-staple such as revenge.

What was absent was a picture like Hunterrr which took for its subject the roving male eye and told us that story like an eye in the sky would.

Great books are written by madmen (The Melvilles, the Joyces, and the Foster Wallaces) who risk failure in order to get at something new and exciting, something that registers to us as truth delivered at the tip of a pen.

The best Hindi movies of 2015 -- magically, almost -- seemed to be mimicking the very spirit of great literature. And it was this spirit that had put those movies in a league unmolested by marketing copy.

As a converse of the good times aforementioned, 2016 was the age of convenience for Hindi movies; of down pat effrontery and planned feeling triumphing over attempts to discern something complexly beautiful.

2016 was when Hindi movies stopped growing beyond interesting premises (Fan: What prodigious poverty of imagination).

It was a year when a Wish Sandwich of a movie (Pink) presented to us the charter for respecting women, and we celebrated it because we already knew its salient points by rote.

2016 was a year when Hindi movies highlighted social problems using a schoolmarm's preferred technique of segregation-and-condemnation (Udta Punjab: 'In these chemically troubled times for our beloved Punjab let us all take a moment and applaud ourselves for being clean and sober.')

The year's most muddled movie was, undoubtedly, Dear Zindagi; wherein Shah Rukh Khan dispensed lessons which -- if you think about them -- were essentially self-cancelling.

Also, I found Alia Bhatt's broken, meandering epigraph to be a far more interesting and wholesome person than her eventual tree-hugging avatar.

I am sure, when the time to shortlist the worst movies of the year would come, critics would roll up their sleeves, and send to the Augean Stables, such soft targets as Shivaay, Rock On 2, Fitoor, Sarbjit and Azhar, and hurl at you aphorisms like how one gave you a headache and the other a toothache.

But don't let all that divert you from the plain fact that 2016 was a year of disappointing Hindi movies outnumbering the downright clunky ones.

For the most part this year, any resonance at the movies was to be experienced in spurts.

There were things that certain Hindi movies did exceedingly well, and sometimes those were reasons enough to establish a connection.

Dangal was no big deal, and what was really fresh about the narrative (which was the whole Phogat Vs Phogat angle) happened at 10 times the speed that all the other template-like stuff did.

But it was a brilliantly cast picture. And I am not talking about the principal characters here, but all those nameless faces that appeared in passing -- they really seemed liked faces that belonged there.

Neerja's director Ram Madhvani betrays a great instinct for 'fracturing the narrative' (he thinks of storytelling in those very terms) and that to me was one of the minor pleasures of watching the movie.

Madhvani may, in the future, make a movie of Endless Tricks: The kind of jazz we can give ourselves over to dizzyingly.

Depending on how you read it, Ae Dil Hai Mushkil was either Karan Johar's best picture or the story of a chocolate cookie experiencing an existential crisis; but there were three performances in there, you just couldn't fault.

Lisa Haydon as the lip-pursing/neck-cranking/cross-drawing sass was one of the real joys of the year.

While the two lead actors alternated between staying on the surface and digging deep, the movie itself waxed and waned before you made peace with that particular rhythm.

The term earnestness is used often when describing talentless actors ('He's no good, so let's just give him "earnestness" for now') but Anushka Sharma is so earnest and brings such truth to her performance that you sometimes wouldn't know whether to take her straight.

Also, Ranbir Kapoor's talent for chewing out Shayari-laden dialogues with the plainest of plain-speak is remarkable in its proximity to a certain post-millennial contempt for glibness.

The entire routine about unrequited love was Bleh, but moments of helplessness, like Ranbir's shivering breakdown outside Sharma's house, with her blank face conveying the hum that's going inside her, were almost unbearably fine.

It was actually in the regional movies of 2016 that the daring of 2015's best Hindi movies could be discovered.

Taking in their native rhythms wholly and unquestionably, these movies created detonations inside viewers' heads.

There was an elation -- a celebration of denseness -- in many of the regional movies of 2016 that was hard to miss; though many didn't really go the distance.

Sairat, for instance, was very effective, but I also thought it was shockingly exploitative. It gets to you in the same way that some of Hitchcock's movies often do -- by working you over.

The dread in Chauthi Koot had the heightened tensions of a horror picture, but it was too detached from a dramatic centre for the movie to come together as one piece.

In a year such as this one, to winnow my list of the five best movies from just one language would be terribly unjust. It would be unfair to the year that was.

So my list here comprises three Hindi movies -- in all of which I saw an unalloyed love for moviemaking and a stab at saying something fresh, something vital.

None of these three were completely successful at what they were doing, but I think their deficiencies only made their leaps more gallant.

On the other hand, No 1 and 2 on my list are two regional movies for which I felt nothing but unqualified love.

5 to 3 (In no particular order): Happy Bhag Jayegi/Raman Raghav 2.0/Kapoor & Sons

A very pleasurable surprise, Mudassar Aziz's Happy Bhag Jayegi is a tale of sweet and terrible enchantment.

When Javed Sheikh, playing a self-deceiving Pakistani politician, terms every minor thing that his son (Abhay Deol) does as an act of nation-building, the movie turns itself into a rip-roaring commentary about the reality of dynasty politics that binds India and Pakistan; it's scary to think how this attitude may even be borne purely out of noble intentions.

Diana Penty's Happy Kaur is a glorified nothing (though Penty herself isn't bad) but it's when she gets the lives of those around her all meshed together that the movie breaks out.

Jimmy Shergil, playing corporator Bagga, doesn't let a beat slip or his swelling-chest sag, and his misplaced vanity becomes a vaudeville act in itself.

With Piyush Mishra, who lets his face wear a perpetual Ninja Turtle-grimace and who keeps his enunciations deliciously salivary, Shergil goes through a series of back-and-forth and together they let the movie morph into a tour de force of hamming -- it's a romp!

Abhay Deol's voice continues to be a technical snag and he holds the cricket bat all wrong, but when the picture finds itself on shaky ground in the second half, it's Deol who injects in it genuine feeling.

Kanwaljeet Singh plays Happy's father who rushes out to have a serious one-on-one with the man who may have eloped with his daughter, but then gets entranced at a sight of hooliganism, forgets his personal pain, and can be seen relaxing over a masculine smile.

The Urdu bits in Happy Bhag Jayegi are raised to a level of conscious artifice and when, in the midst of all the confusions, Ayesha Raja and Jagat Rawat are forced to play wingmen trying to suppress a domestic/national conspiracy, the two team up like comic, sweet-souled reincarnations of the witches from Macbeth.

Anurag Kashyap's essayistic movie is more Norman Mailer than Raman Raghav.

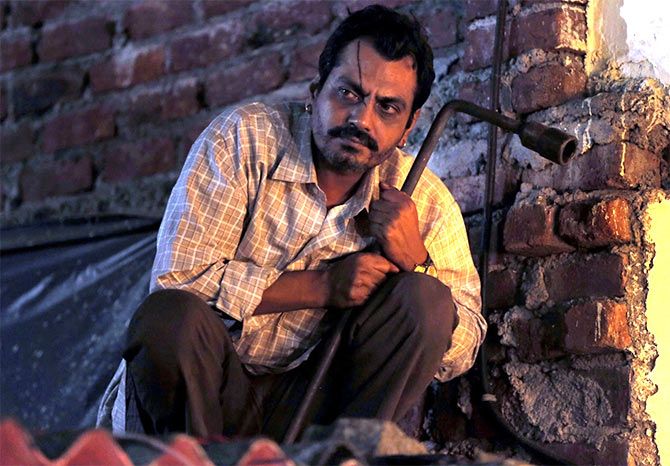

Like Mailer's hyperventilated descriptions of the psychopath, Nawazuddin Siddiqui's Ramanna exists only to prove to the world, that he is a hipster in a world of squares: A killer with a philosophical turn of mind. (At one point he says to a policeman who is reading him too linearly: Aap Baatcheet ka Rass Nahi Samajhte.)

Kashyap discovers a sense of paranoia in scenes of everyday life; noodles around for humour; gives us what could be construed as a moment of tenderness; and then spills blood.

In the process, he makes us identify with both the killer and his terrified victims.

Nawazuddin drains so much out of himself that in some scenes he seems to have imbibed the asceticism of Bressonian actors.

Vicky Kaushal sheds the wide-eyedness of his Masaan character and looks like he is constantly staring inward.

The deliberate creation of intimacy within the acts of murder points to the fact that this is an exploration mounted as a movie. But then, the picture ends up only half-exploring.

Kashyap gets high on his recently-acquired tendency to 'play the director' and hems and haws when he should have been fluidly putting his imagination to work.

'Murdering someone can be a great charge,' Martin Amis had once theorised. Is that a general human trait?

This is one of those movies that can be best enjoyed when you put judgment aside and give yourself over to it.

'This is his best performance and Kapoor & Sons is the best Dharma movie to date.'

Shakun Batra trying to do a Woody Allen is not too different from Woody Allen trying to do a Bergman.

There's a self-consciousness that creeps into scenes when they are created using questions like, 'How would Woody Allen set up this thing?', or, 'How would Billy Wilder solve this problem?'

But Batra is a persevering celebrator of his idols; he thinks deeply about them and their work, and in trying to emulate them, creates in Kapoor & Sons, wonderful, three-dimensional characters; characters who are all yearning for each other but also trapped into being with each other.

Often the fittings in a home indicate the saneness of its dwellers, and Batra creates a home with plumbing problems and creaky doors.

The arcs of the characters are implied through directions each of them take when left to their own devices.

In a wonderful scene, the two brothers arrive at their home, and separately go through their paraphernalia from childhood.

The world of Kapoor & Sons is one in which Soap Operaish problems interrupt the ordinary experiences of its characters, and the movie suggests the rhythms that might be felt if TV Soap Opera was done in a non-manipulative manner.

Batra comes across as rigid when shooting scenes of chaos -- those scenes do seem a tad 'too directed' and controlled. But when the family members sit around their sofa and sing songs or narrate little absurdities to each other, they seem to be living off every surprise that's thrust upon them.

I thought Rishi Kapoor's Punjabi Falstaff-like character was overwritten and too gregarious, but Ratna Pathak, Rajat Kapoor, Alia Bhatt, and Fawad Khan pitch in with life-like performances -- often inhabiting multiple emotional states within a single scene.

However it's Sidharth Malhotra who takes on the movie's most difficult role, and who comes up trumps, making us feel his bridled hurt and resentment. This is his best performance and Kapoor & Sons is the best Dharma movie to date.

'This is a masterpiece of gossip.'

2. Maheshinte Prathikaram

An exploding star of a movie.

Structured like a Sierpinski Gasket -- with random incidents and characters adding up to a course-changing event -- and with individual scenes cascading in the manner of Domino Effect, leaving in their wake disorder and commotion, Maheshinte Prathikaram is about the rhythms of life in small-town Kerala and how we often discern larger patterns and meanings from the discrete bits of information available to us.

All this might lead you to believe that Maheshinte Prathikaram is some kind of a complicated mathematically-structured picture, while what it actually is, is a picture of boundless joy.

Fahadh Faasil's Mahesh vows revenge on the man who humiliates him publicly. And as a symbolic reference, Mahesh pledges to not wear his slippers till he delivers the payback.

It's a pledge of mythical proportions, like those rural ballads, and becomes a matter of great interest for those around Mahesh -- his revenge is now an apocalyptic spectacle waiting to happen.

The title (Revenge of Mahesh) is just a placeholder, for director Dileesh Pothan builds an entire world out of one man's thirst for revenge (the movie could even have been called The World of Mahesh).

Pothan is a poet of the commonplace, and doesn't just possess a remarkable eye of detail, but also a feeling for detail.

Working with cinematographer Shyju Khalid, he turns elements of nature into all-seeing spectators.

There is a persistent effort to humanise even the most despicable of characters here.

This is a movie in which the villain is first introduced as a pacifist trying to stop a fight from taking place; and it's only after Mahesh pushes him does he lose his bearings, and go all out.

Fahadh and the rest of the actors' great success, is in making you feel like they have a real history going –- they constantly refer to events from the past using half-constructed sentences.

Maheshinte Prathikaram is an almost exposition-free movie, where you learn about people and their lives from the way they talk and whisper to each other.

This is a masterpiece of gossip.

1. Thithi

Raam Reddy gives us a motion picture that alludes to Alice Munro's theory about writing great characters: 'Don't dissect people. Celebrate the essential mystery.'

In Thithi, it's the essential mystery of each character that we are made to follow, as a plot slowly develops around our pursuit.

When quizzed about his native town, an old man says, "I am from where I am." The characters never tell us who they are, and most of them are just going through the motions, but when they stop to make small talk or parade their concerns, they also end up revealing something deep-seated about themselves.

The story concerns the death of a 101-year-old man (Century Gowda) and how it brings together, for practical purposes, the three generation of Gowda sons.

The grandson Thamanna wants to sell off Century Gowda's five-acre property and for that he needs either his father Gadappa's absolute consent or his certain death and when he can't achieve either, he sends his father away and asks him to lie low.

Also in the mix is Thamanna's son Abhi, a hustler who is less like his father or grandfather –- a decent hardworking man and a Satyr-poet respectively -- and more like his great-grandfather Century: a man with the juices.

The setting is dry and sterile, and is yet magical, like a Carl Haag painting. The characters' account of simple things has the quality of folklore.

The women mostly exist as voices, but even as voices they dwarf the men. In its matter-of-fact treatment of tragedy the picture has the clarity and beauty of Renoir's best works.

And the humour keeps breaking through, giving the narrative an air of wooziness.

Thithi is not just the finest Indian movie of the year, but also the most unembarrassed Indian picture since Ketan Mehta's Bhavni Bhavai.