ISRO’s PSLV-C39 mission to launch the IRNSS-1H satellite was unsuccessful when the heat shield failed to separate in the dramatic last few minutes of the flight . The rocket performed as expected and closely matched the expected trajectory till the time it was supposed to release of the satellite. The command was given for the separation of the satellite, and for the next few seconds, an announcement of a successful launch was anticipated, but there was an unusual silence on the ISRO livestream.

The PSLV is so predictable, that once the rocket has taken off, it is taken for granted that the satellites will be deployed. Congratulatory messages were posted on social networking platforms, and some news sites even pushed out reports on a successful launch. Then, it was announced that the heat shield had failed to separate, and that ISRO will investigate the issue further. The live feed of the launch on ISRO’s site was cut abruptly. Still, the launch was nothing short of spectacular.

What a sight 😍😍😍 #ISRO #PSLV launch from Sriharikota caught on cam from Kathipara Junction in #Chennai #ShotOnS8 @SamsungMobileIN 👍 pic.twitter.com/jTOlfotcBA

— Dr. T R B Rajaa (@TRBRajaa) August 31, 2017

It was an unexpected failure for the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), which had enjoyed a flawless launch record so far. It was also a setback for the Indian regional navigation satellite system (IRNSS), which aims to provide space based geolocation services known as navigation with Indian constellation (NAVIC). The name has a double meaning in Hindi, where it means a person who operates a boat.

The naming is apt. When the constellation is operational, fishing vessels can be directed to areas where the yield is likely to be high, and be warned of bad weather conditions or when straying into the territories of other countries. The constellation would have been fully operational if it were not for the last minute glitch on Thursday.

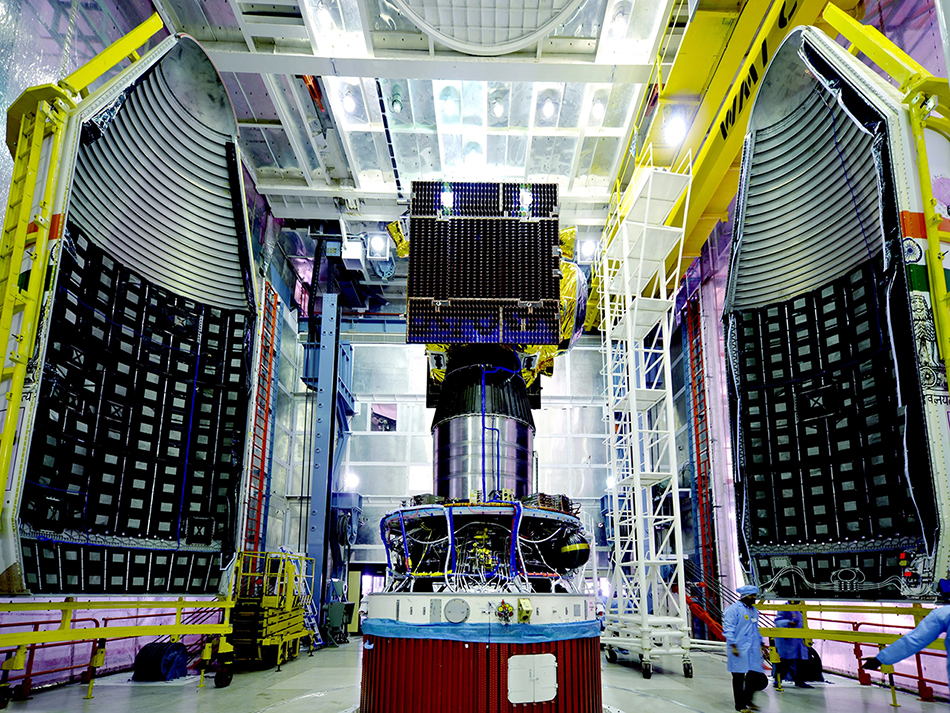

The heat shield is the conical structure right on top of the rocket, above four stages and the strap on boosters. It is attached to the fourth stage of the launcher. The heat shield protects the delicate electrical instruments on the satellite during its perilous journey from the ground to space. Once in space, the heat shield separates like a blooming flower with two petals, and deploys the satellite housed within into its intended orbit.

The satellite is hoisted into the heat shield during the integration of the rocket, prior to launch. While all the stages of the rocket performed as expected, it was just the heat shield that failed to separate at the last moment. If ISRO officially chalks down the mission as a partial failure, and not as a total failure, it will do justice to the illustrious record of the reliable workhorse rocket that is the PSLV.

The biggest disappointment here is that the workhorse rocket of ISRO, the PSLV, may no longer has a flawless record. Apart from the inaugural launch in 1993, 37 consecutive PSLV flights have been a success. The PSLV remains one of the most reliable launch vehicles currently in operation. The final update for the mission simply says “ PSLV-C39/IRNSS-1H Mission Unsuccessful .”

Providentially, the only passenger on board was the IRNSS-1H navigation satellite. Previous PSLV launches including the PSLV-C38 and the PSLV-C37 missions had multiple nanosatellites piggybacking on the ride along with the main payload.

Had more satellites been fitted into the PSLV-C39 mission, the scale of the disaster would have been much bigger. The losses would have been higher because the contracts for the launch would have been signed by ISRO’s commercial arm, Antrix (pronounced as Antariksh, the Hindi word for outer space). Typically, the multi satellite launches include academic satellites that take years to develop, which would have been particularly disappointing for educational institutions and the students involved. Fortunately, the loss has been minimal because of the single satellite on board. This was a good mission to fail.

Each satellite in the IRNSS constellation costs Rs 150 crore, and the PSLV launch in the XL configuration costs about Rs 130 crore. The total loss from the failed PSLV-C39/IRNSS-1H mission is therefore around Rs 280 crore. This figure is restricted only to the satellite and the vehicle, and as such, is incomparable with the costing of other launch services.

Apart from the seven satellites in orbit, the IRNSS system has been planned with two backup satellites on the ground to keep the system up and running in case anything goes wrong. Moreover, ISRO has plans to increase the number of active satellites in the constellation from 7 to 11.

The initiative took off with the launch of the IRNSS-1A on 1 July, 2013 . Manmohan Singh, then the Prime Minister of India, had said that the launch was “an important milestone in the development of India’s space programme.” From then on, the satellites were launched regularly. The satellites mostly weighted 1,425 kg each, were identical in dimensions, and placed into a Geosynchronous Transfer Orbit (GTO).

The constellation of seven satellites had been considered as complete with the launch of IRNSS-1G with the successful PSLV-C33 flight in April 2016. The IRNSS constellation would have been India’s own satellite navigation system, similar to the American Global Positioning System, the Russian GLONASS, the European Galileo and the Chinese Beidou. After checking the signals from prototype receivers on the ground, the satellites in space and the ground stations, ISRO would have formally declared the IRNSS system as operational. However, it was not meant to be.

Over a period of six months, the precise rubidium clocks on IRNSS-1A started failing . Around the same time, the clocks on board the European Galileo system also started failing. ISRO had imported the clocks from an international supplier. It is still not known what caused the clocks to malfunction, but the atomic clocks used in both the European and Indian navigation constellations were supplied by Spectratime .

ISRO continues to use the messaging capabilities of IRNSS-1A, and it is just not more debris in space. Each IRNSS satellite has three clocks, and needs only one to operate. The other two are there just for redundancy, but all the three atomic clocks on the IRNSS-1A failed. There were some reports that two additional atomic clocks had failed in the other satellites, but ISRO dismissed those reports as rumours .

The IRNSS-1H that failed to deploy was supposed to be the replacement for IRNSS-1A. It was the first satellite that ISRO had fabricated in partnership with private industries from India . While addressing the press after the satellite failed to deploy, ISRO chief AS Kiran Kumar made it clear that partnering with private industries was in no way connected to the heat shields not separating on the mission.

The satellites have a planned mission life of 10 to 12 years, but ISRO spacecraft have been known to continue to work for long after their planned duration. The original planned mission duration for ISRO’s first interplanetary spacecraft, Mangalyaan, was only supposed to be about 183 days, but even after a 1,000 days, the spacecraft continues to beam back observations .

Once it is fully functional, the NavIC constellation promises to provide a range of critical services, including disaster management and search and rescue operations. The constellation has been planned to provide a positional resolution of less than 10 meters, once it is fully operational. Apart from the standard positioning service, a restricted service on encrypted channels will be available to the military, who can use the Indian geolocation services without relying on the constellations of other countries.

The NavIC constellation is meant to cover an area 1,500 km from the borders of India. It can be used for terrestrial, marine and aerial navigation as well as vehicle tracking and fleet management. Visual and voice navigation services can be extended to drivers, while hikers, travellers and trekkers can track their movements on the ground. Once the constellation is operational, the government plans to integrate IRNSS capabilities in mobile phones. An interface control document for various applications is already available.

Maintaining the IRNSS constellation is a continuous process, and ISRO will have to replace the satellites as and when they stop being functional. Three redundant clocks, eleven satellites, two grounded backups, ten to twelve years planned mission duration, do the math. Even if the satellites fractionally exceed their planned mission duration, they will end up as a tremendous benefit to a significant portion of the world’s population.

The IRNSS constellation is currently in the same state as it was prior to the PSLV-C39 launch. ISRO will have to launch another navigation satellite to replace the failed atomic clocks on the IRNSS-1A.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)