It all began in the month of July, 1994 in the city of Bhopal. In a cavalcade of Gypsy jeeps, Ambassadors and a few Madhya Pradesh police vans, KPS Gill, the then DGP of Punjab Police arrived at hotel Lake View Ashok, then the destination in Bhopal. Gill was fighting the Indian Hockey Federation (IHF) elections. The cop who had cleaned up Punjab now had his sights on Indian hockey.

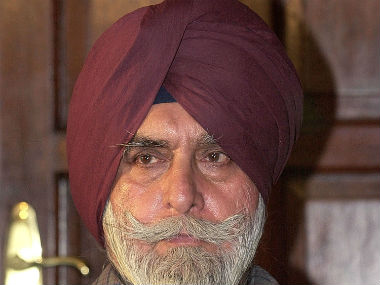

Gill got out of the back seat of a white-coloured Ambassador. Six feet plus, Indian hockey had never seen anything like him. Light blue turban, steel grey trousers and sky blue shirts were his fashion staple. His twirled moustache on a good day had the perfect roller-coaster loop. He stood erect, the turban giving him those extra inches to dwarf others. He had this habit of not looking at anyone. People seemed to cower before him. His reputation, rank, fame and ‘notoriety’ always arrived before he did.

Cleaning Punjab of terrorism had left dark smudges of deaths, fake encounters and state murders on those dark grey trousers and light blue shirts. People backed off when he climbed out of his official car. The media was already assembled there. Photographers clicked away. Those were the days of print hacks. The wolves’ pack of TV reporters were yet to arrive. Everybody was in awe of him.

Usually, when he climbed out of a car, an uneasy silence of 20-30 seconds followed before someone approached him. At the Lake View Ashok hotel, a local reporter, short and shifty, standing in front, called out to him. “Gill sahib,” he said. “Kya aap election jeet sakte hain? (Mr Gill, do you think you can win the election?”) Gill paused, which was enough to cast a chill, slowly turned sideways, looked at the reporter and said, “This election is a mere formality. I am the IHF president.”

For the next few days, Bhopal was like the outpost; Carson City in a Louis L’Amour novel. Punjab Police cops in plain clothes roamed around like hustlers, guns visible in their waist bands or at the back, shirts barely concealing the fire-arms presence. The city itself had stopped; like holding its breath. Gill’s rival, Gufran-E-Azam of the Congress accused Gill of strong-arm tactics. It was true that Gill’s officers were meeting various association representatives asking them to vote for the ‘Super Cop’.

Gufran forced the Madhya Pradesh government to complain to the Centre about the strong-arm tactics of the Punjab Police officers roaming around Bhopal. Gill, in those times, was ‘untouchable’ and ‘powerful’ and the home ministry quickly distanced itself saying a visiting VIP’s security was the state government’s responsibility. Gill won the elections. The undertaker had arrived.

Yet, his initial days as IHF president gave huge confidence. He appointed Cedric D’Souza, then the Air India coach for the 1994 World Cup. And promptly arrived in Sydney for the India versus South Korea match. India won. Gill threw a party at an Indian restaurant in Darling Harbour, right next to the hotel where the team was staying.

K Jothikumaran, the IHF secretary, who would one day be the lymphoma that would bring Gill down, saw the grandeur of the man for the first time from such close quarters. He was the man who had brought in votes from the southern state. For a man of Gill’s intellect and tastes, Jothikumaran was the anti-thesis. He was the arrack sitting next to the expensive single malt. India finished fifth at the Sydney World Cup; up five places from the 10th finish at the 1990 Lahore World Cup. Gill immediately rewarded the players with money, if not much, he did his best with the government where strings could still be pulled. We all believed and rightly so that Gill’s presence had lifted hockey out of the morass it had been stuck in for so long.

Things went well. Money came in, Gill believed in Cedric and gave him a free hand. In the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, a combination of bad luck and brittle defence did India in. It was also the first time that Gill asked for Pargat Singh, the 1992 Olympic captain to be a part of the team. Though Cedric has never voiced his opinion but insiders say and believe that Pargat was thrust on Cedric. In Cedric’s 1994 World Cup team, Pargat was never in the scheme of things.

India finished eighth. Cedric lost his job. He would be the first in a list of 18 coaches who would lose their jobs under Gill. Vasudevan Bhaskaran had taken the Indian junior team to the final of the 1997 Junior World Cup. It was Gill’s first big achievement as the IHF president. He was given charge of the senior team for the 1998 Utrecht World Cup.

India crashed in Holland, finishing ninth. Bhaskaran was shown the door. MK Kaushik came in for the 1998 Asian Games but by then Jothikumaran had started tinkering with the team. India won the Asian Games gold. Gill, in a press conference at New Delhi, sacked Kaushik and rested six of the senior players. The IHF president had given way to the ‘Super Cop’. In five months, a successful coach had been thrown out and Bhaskaran had been brought back. It defied logic. Gill wanted immediate results. He wanted a podium finish. The man who had emerged a hero in Punjab wiping out terrorists couldn’t understand why he couldn’t clean up a sport, where India had won eight Olympic medals, in the same clinical, efficient manner. Bhaskaran was there till the 2000 Olympics before Rajinder Singh senior came and gave some relief to Gill by winning the 2001 Junior World Cup.

But Gill thirsted for victory on the big stage. Tired of the coaches and frustrated by the backroom manipulations, he brought back Cedric, probably the only coach he ever trusted along with Rajinder.

At the 2002 World Cup, India crashed starting with a draw against Japan and then losing to hosts Malaysia. With two matches still to go, Cedric was removed. Jothikumaran had finally taken over. He was the poisoned chalice that had finally come of age.

Rajinder came in and gave India the 2003 Asia Cup. Weeks before the 2004 Athens Olympics, he was removed and in came an unknown German Gerhard Rach. Athens was a disaster. Gill had started popping coaches like pills. By the time the 2006 World Cup came around in Monchengladbach, Bhaskaran was back. India was running out of coaches but with Gill being blinded by the core team of Jothikumaran and himself losing serious interest in the sport, India finished 11th at Monchengladbach. They did win the 2007 Asia Cup in Chennai under Joaquim Carvalho, an 1984 Olympian, but lost the Olympic Qualifiers in Chile and for the first time in Indian hockey history, an Indian hockey team was not there at Olympics, in Beijing in 2008. Gill was sacked by the Indian Olympic Association (IOA) in 2008 along with Jothikumaran who had been caught in a TV sting taking bribes to induct players into the national team.

It’s early morning in Vienna when I call Cedric to tell him that KPS Gill had passed away. Cedric had already heard. He speaks glowingly about Gill. “He gave me an opportunity to coach the national team,” he says. “Listen, a lot of people will say a lot of things but he tried to do his best to get hockey back.”

Cedric recalls that Gill called him in 1994 to his house in Chandigarh for a meeting. Gill had just become the IHF president. “He was rushing out for a meeting with the Punjab chief minister and I told him to come to the stadium and watch my team Air India play the final with ASC. He asked me about the result and I said Air India will win 3-1.” Cedric believes that predicting the result convinced Gill about hiring him as the national coach. “It was a honour for me,” says Cedric.

Rajinder is in Patiala and genuinely sad that Gill is no more. Rajinder coaches at the National Institute of Sports and remembers that Gill asked him after Cedric had been sacked in 2002 if he wanted to coach the national team.

Rajinder, obviously, said yes. “I can tell you one thing and that Gill never interfered with the selection,” says Rajinder. “I got my team and I made them play.” Rajinder remembers Gill asking him what was wrong with the national team. And Rajinder said, “They lack national spirit.” Gill promptly put the team at the NSG headquarters and six-seven senior players revolted at the lack of a proper ‘star hotel accommodation’. Gill told the players to leave immediately. The next morning those players were there ready to take on the NSG obstacles. Rajinder describes Gill as a “gem of a person” and adds, “I really don’t care who thinks what about him, but the man cared for the national team.”

It’s amazing that all the sacked coaches, treated shabbily by Gill at some point, actually speak very highly of him. Rajinder was removed from the coaches’ job in Dusseldorf, just weeks before the 2004 Athens Olympics.

“Jothikumaran wanted to bring in Adam Sinclair, a player who had not played even the national championships. And they wanted to remove Kanwalpreet and Bimal Lakra. I refused and gave a piece of my mind to Jothi. He went and complained to Gill who called me to his room there in a hotel. I was asked to take the team to Athens minus the players I wanted. I refused and told Gill that Jothikumaran was manipulating him. I was told to leave for India.”

Rajinder says before he left the hotel to go to Frankfurt to take a flight back to India, he touched Gill’s feet. “But he was so embarrassed that he didn’t look at me. Just silently asked me to go,” remembers Rajinder.

Cedric believes that the system finally got to him and that he became a victim of the manipulations of the voting pattern of the IHF pulled by Jothikumaran. “Being sacked in the middle of a World Cup is ego-crushing,” says Cedric. “But my deepest respect to him as I never held it against him.” The former Indian coach also speaks of an evening in Chandigarh where he was tired after a heavy session of training with the national team and called Gill and said, “Wish I could listen to some jazz.” Gill’s car promptly arrived at the sector-42 stadium, picked up Cedric, took him to Gill’s house where the IHF president ushered him into a room and pointed to a modern music system and said, “Jazz is right there.” Cedric listened to two hours of jazz alone and went back to the stadium.

Rajinder also refers to Gill as a “soft man”. It’s a phrase that is also echoed by Tan Sri Alagandra, the former secretary-general of the Asian Hockey Federation and also a former Olympian, having played in the 1956 Olympics. One thing was common between both Gill and Alagendra was that they were policemen; Alagendra having retired as chief police officer of Selangor, Malaysia.

Genuinely saddened by Gill’s demise, Alagendra says, “He was the finest Indian man I have ever met. I used to pick him up at the Kuala Lumpur airport and he stayed at my house during Indian hockey tours or AHF meetings. I gave him security because he was a marked man. He was a good friend of Malaysia and extremely close to the Sultan Azlan Shah.”

Alagendra who travelled extensively with the Malaysian hockey team recounts a visit to Brussels where he and Gill stayed at the same hotel during an FIH meeting. “I came back to the hotel and at the reception there was a note that said ‘come down to the restaurant three shops down the road’ and it was signed by Gill. I went there and a few people along with Gill was there having Kentucky Fried Chicken and beer. One of the waiters who was Indian went up to Gill and said ‘Sir, you look like KPS Gill.’ Gill replied saying that he was indeed the KPS Gill. The waiter shook Gill’s hand and went away. Sometime later, after we had a bucket of chicken and beer, three men suddenly came in brandishing a sword and tried to slash away at Gill. We intervened and there was Robert Watson from the UK. We saved Gill and the attacker ran away. It was obvious that the waiter had called them. The Brussels police chief came and advised Gill to return to India. I also told him to leave which Gill listened and took a flight home.” Alagendra also spoke about evenings of bhangra music and drink in Kuala Lumpur.

Colonel Balbir, a 1968 Olympic bronze medallist, speaks of Gill as a man who attempted to change the environment in which hockey was drowning. “He meant well and I have met him so many times when he wanted me as a manager that his only queries used to be on how to improve the general playing level of the national team.” Balbir admits that a great start finished off terribly for Gill. “But he had himself to blame as he got caught in a team that exploited him and his weaknesses.” Balbir remembers an evening where he and Gill were sharing a drink and he asked seriously as to why the Indian forwards were missing so many goals. After listening to Balbir’s technical analysis of missing and scoring goals, while a waiter replaced his single malt, Gill dead-panned, “Give them a few Goris and they will learn how to score goals.”

Maybe, Gill didn’t have the tactical dexterity and patience required to handle the politics of a federation. He probably thought it would be an extension of his role as DGP, Punjab Police where one command brought the entire state police to his door step; a phone call sent files racing through the home ministry and brought trepidation to ruling chief ministers.

The IHF was pock-marked by members who had won elections at the state level and knew, till they had the votes, Gill could be twisted and turned. Gill, who would be found in a book shop, intently reading, if he went missing in an airport with the flight only minutes away, makes you wonder what the hell he was doing in a place like a sports federation, which in normal parlance in a nation like ours, would be called a ‘viper’s nest’.

He came into hockey to quote US president Donald Trump “to clean the swamp” but fell victim to the very animals who lived in it. By the time he was sacked, the IHF was reeling from the idiocies of mismanagement and corruption and now he would never have the opportunity to say this but the end of his tenure was like a salvation for him; a release.

Sadly, there will be no redemption for Gill. To cut the flesh and make it bleed, one can call him a half-baked messiah. He was a charismatic, powerful, intelligent man about whom it was hard to be objective. But his credentials came at a high price to his tenure as IHF chief as well as for the sport. He was like the King who could never be Emperor. In Gill’s world, hockey slowly took on the pallor of a hallucination. Reality was otherwise.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)