The plan was to get away. The plan is to always get away.

It’s seven in the morning and I’m staring at a snow capped mountain with an intensity which only comes after years of staring at various glowing screens, passively wondering if the all the ice in the world would actually melt before you will finally devise an escape plan.

The air is thin and cool. The sky, Vermeer’s blue.

I am told this is not the ‘season’ to be here. As if there is ever a season or a precise time to redeem a soul. But on more earthly reasoning, I’m glad to be here this time of the year. The landscape seems more at peace with itself, the streets empty, the locals extra friendly. It’s cheaper to fill your stomach and easier to find a bed.

The entire stay was planned around a couple of treks which would never materialise. All the research into various trails and camping gear never used. All the vivid daydreaming of cold nights under the constellations would never come to pass.

But right then, I was just awestruck and cold.

I had borrowed a jacket from a friend’s friend and tested its limits the night before when I took a rickety bus in desperate need of new breaks through the hills in the darkest of nights.

There is a board where I stand telling how far Seoul, Tokyo, New York, Paris, and London are. I ignore it and take in the view. I don’t believe in omens.

*****

There is a painting on the wall of a girl eating noodles out of a bowl. The colours are warm, there is steam rising from the food as she cools a spoonful held close to her lips. Somehow this simple act seems oddly comforting.

It’s drizzling outside, a token of what was to follow in the coming days conveniently ignored sitting behind the glass windows of a café. The place is warmly lit and compliments the dark surroundings of the painting.

I use a blunt pencil to write down my order on a piece of paper. Thenthuk — a thick, square handmade noodle soup with veggies — and some momos. The owner’s smile assured me it is the best decision I had made in my life, or going forward, will ever make.

One learns to empathise with Sisyphus pretty quickly taking to the streets here. Any time you step out, it’s either a steep climb uphill or a feeling that your legs will run away without you downhill. And no matter which one you take, soon you will have to trace your steps in the other direction. Over and over, till your legs turn into jelly or start resembling someone only subscribing to leg days at the gym.

The food arrives. It’s better than I expected. It’s better than you expected. It smells of freshly cut vegetables and has an earthy flavour. The momos have an aftertaste of garlic, and cheese.

There is a cold wind blowing outside now and someone gets up and shuts the entrance door. The sound from outside ceases, hushed voices fill the room. I take off my jacket and hold the bowl of soup, warming my hands. Sometimes, it doesn’t take much to feel comfortable in a foreign land.

Sometimes, it doesn’t take much to feel comfortable in a foreign land.

A nun walks in front of me. Short, stooped and Ian McKellen in Mr Holmes old, she carries a walking stick taller than herself. It’s raining again and I’m overcome by strange sense that if I overtook her, it would somehow be disrespectful. Strange because we are walking on a moderately crowded market street. I can pass her easily, but I don’t for a while, just staring at the maroon of her robe, the rhythmic movement of her body as she walks. We are headed for the same destination, anyway.

The inception of streets from the main square resembles rivers flowing from a glacier in all directions. All downhill, all narrow, all flowing with people.

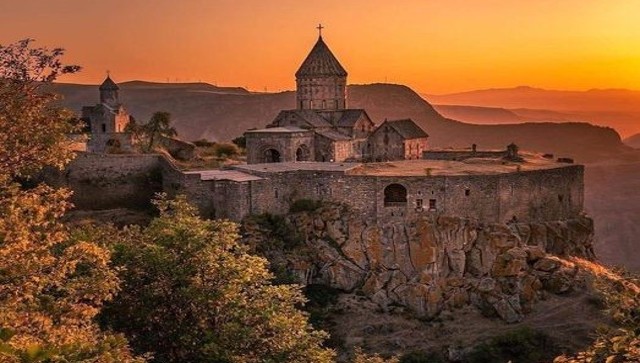

The one I am rolling down leads to the Tsuglagkhang Complex, the residence of His Holiness, The Dalai Lama, and home to a number of small monasteries and stupas. This is where the Dalai Lama offers his teachings; this is where you head when that feeling of eternal doom starts closing in.

The place looks exactly like the image you get in your head when you hear the word ‘complex’. It hardly stands out from the outside but is quite inviting when the clouds roll into town.

A small door opens into a modest Tibet museum before one goes through the security and takes a flight of stairs up to the main temple. Here the artifacts recount what decades of oppression, fear, systematic disintegration of a culture, losing one’s homeland and resisting powers far mightier than you feel like here. Lessons for generations.

There are just a few people around the main temple grounds. Everyone seems to be moving in different directions. It’s quiet, but not the kind that hurts.

Suddenly that feeling of being a tourist tightened around my face. I proceed towards the prayer wheels, adding my touch to the millions who had come before, hoping at least a few of those might have felt as lost as I did in that moment.

There is a glow to the temples inside. It’s not unreasonably bright; it’s just as if a bright golden colour has seized every corner. The place is spotless. Boxes of chocolates, juices, candy, honey, and what not are arranged neatly in front of the statues of deities. Offerings from a modern economy.

It’s still raining but I head for the exit. There a small room with a giant prayer bell at its center as I head out. I turn it and a bell rings when the rotation is complete. I turn it again with a little extra force on my way out. A toddler stares at me, unimpressed.

I leave the room but stop in earshot of it, waiting for the bell to ring.

I take the corner back seat so I can see the entire place, although it’s not a big set up. Actually, it’s quite modest.

My order is taken by a middle aged man who then disappears behind a curtain into the kitchen. People come and go. A large quantity of steaming food and beer is handed out of the kitchen. A woman sits on the table to my side cutting vegetables and talking to whoever walks in. Once she goes into the kitchen, suddenly it is very quiet.

The place is warm and has an air of privateness. There is no one behind the counter in the café, just a dog rolled up under the chair. A different smell pours out of the kitchen every few minutes. It’s late into the night and raining outside. I feel like an intruder.

The day has been shades of gray, darker with every passing hour. A storm rolled into town in the evening. A wall of clouds moved in swiftly, swallowing first the mountains, then the hills, the houses, my balcony. Purple lightning and thunderclaps.

Trekking now seems like a far-flung fantasy in this fantastic country. The cafés will have to do.

The food is bought out and served with such generosity, it would suggest grave disappointment on the part of the management if I did not enjoy it. Tingmo (steamed bread) with soup and brown-flour momos. Enjoyed for the entirety of the next hour.

The wall to my side holds photographs of three men who own the café. One sings into a microphone, another plays the guitar and the last one behind the drums. Tibetan musicians Jamyang, Jigme and Ingsel, the JJI Brothers, are enveloped in hues of reds and greens of concert lights, doing their part for their lost country.

The rain subsides and I quickly pay and step outside. There is a different feel to the town at night. Most of the shops are shut, only the cafés remain open.

Bright lights pour out of the windows into the cold, clear rainy streets.

Looking into the windows you can feel the pulse of a place. You can almost taste the food on the tables and feel the drinks on your lips.

Hundreds of conversations about thousands of things under millions of stars in golden lit rooms.

*****

“…magnificent in the full shimmer of moonlight, appeared what he took to be the loveliest mountain on earth… so radiant, so serenely poised, that he wondered for a moment if it were real at all.”

In his 1933 novel, Lost Horizon, British author James Hilton writes of Shangri-La, a mystical land far west of Tibet. His fictional land, guided from a lamasery, became synonym with earthly paradise.

The description of the peaceful and conflict-free valley struck a chord with many across the globe during the time of World War II and has continued to do so over the decades, something to strive for.

Just like Hilton’s valley, café Shangri-La can evade sight. Nestled at the end of a corridor from one of the main streets, the café, perhaps fittingly, is run by Buddhist monks.

But the place seemed to assume the paradisiacal quality of its mystical namesake, as I couldn’t get in. I was too late one night, too early the next morning, and then the chance slipped away.

The smell of my pocha (a salty tea churned with butter) brings me back to the café I’m actually sitting in. This one looks more like a conventional café (at least the ones I’m used to), and also comes with a recommendation from a popular TV show.

A young monk, about ten years old sits across from me on the table next to the glass window. Clad in maroon and head shaved, he is accompanied by an older monk, I would say in his eighties, but it’s difficult.

Between looking out of the window, which is partially opaque with steam after to the rain, and his food, he glances over at me with a hint of a smile. He only nods in response to anything said by the old monk. Not a word is spoken.

To my side sits a family. Four adults and two children. The kids the same age as the young monk, but with multicolour clothes and long hair, creating a bit of ruckus, but all good natured.

As I look at the two monks and the family, their tables, like their lives, divided by a thin wall, I wonder what their Shangri-Las would look like.

Is it in Hilton’s vision of a grand promised land, “a living essence, distilled from the magic of the ages and miraculously preserved against time and death”, or is it something much more fleeting and personal?

Perhaps a cup of butter tea in café of a mountain town, residence to a spiritual leader and home to refugees, as the raindrops crash on glass windows.

*****

The window gives a particularly spectacular view of the valley down below, the mountains in a distance. Although it’s morning, I can imagine the misty sunset in the evening, the sun casting its last rays into the café through the glass pane as twilight approaches.

A girl is sitting next to it, blocking my view partially. Her shoes are next to a chair, but not the one she is sitting at. Not even the next one. It’s a completely different table. Her bag hangs on yet another chair. She is reading a book but seems quite distracted by the place itself. She calls the waiter and asks him to cancel half her order. Then call him again orders something else. She then proceeds to abandon her latest table, leaving yet another of her belonging behind, and moves to the window. There she drops her jacket and moves to the sofa away from the tables. Her tea arrives but she is not happy with the honey in it. She calls the waiter again and asks him to bring the entire box of honey from the kitchen and proceeds inspects it, questioning him where it’s bought from and the particularities of its contents.

Self-consciousness is a vice.

I scan the few bookshelves surrounding me, ignoring lessons on honey making and fair trade.

I pick up Joyce’s Dubliners and skim through the introduction pages as I finish my breakfast — some bread and mint iced tea.

I turn to the first story, The Sisters.

“There was no hope for him this time,” reads the opening line.

I close the book and ask for the bill.

*****

The weather finally cleared up one morning. The morning I had to leave.

I pack my bag and ascend towards the main square, pushing myself up the steep incline for one last time, the straps cutting into my shoulders.

The roads are just drying up as the sun slowly makes its way to the alleys.

Today is Tibetan Uprising Day and I can feel the undercurrents. There is a protest march planned later in the day, but I won’t be here to see it.

I buy a bus ticket, but there is some time to kill. I go to a nearby café. It’s on the first floor and overlooks part of the town.

The last few days seem surreal in this moment. The gray skies, the thunderstorms, the snow, the rains and the mountains. Entire days spent at cafés, monasteries and walking around the small town, and nights curled up in blankets and listening to the howling winds outside. The maroon robes and the stream rising from the food.

Just yesterday, I found myself back in Tsuglagkhang. It was an unplanned visit, almost instinctive.

I could hear the chants coming from the complex in the market as I desperately looked for souvenirs, all the while realising the futility of the act (I ended up buying some post cards).

As I approach the main temple, I could hear the chants getting louder, flowing through me.

There is a sea of maroon cloaks, all chanting in unison. Surrounded by the golden light of the temple as it rains outside.

There are a few spectators like me, rooted to their spots in awe. I swear, if I had closed my eyes right then, I would have slipped away.

It has been an unexpected journey. Just like they all should be.

I pay for my breakfast and start walking toward my bus.

Someone honks from behind and I give way without turning to look.

A guy in a leather jacket zooms past me on a Harley.

There is a Tibetan flag tied around his neck like a cape which flutters in the air behind him. Red, blue, white and yellow.

A superhero of the land. And as for his super power, hope shall do for now.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)