The magnitude of the carnage may be impossible to emulate in a democratically elected republic, but the thought behind Pol Pot's atrocities is not too far away from home.

In the heart of the busy streets of Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, lies a museum called Tuol Sleng, or S21. A half hour bike ride from S21, around 17 kilometers south of central Phnom Penh, sits an old serene orchard in the outskirts of the city, known as Choeung Ek. From concrete constructions to greenery is how one could aptly summarize this half hour journey. But for thousands of Cambodians during 1975-79, it was the final journey of their life.

S21, a genocide museum, used to be a school prior to 1975. The place of laughter and lessons, where innocent kids found expression, became a torture centre under the Khmer Rouge, the guerillas that formed the communist party led by Pol Pot.

Since the Vietnamese at war with America used Cambodia as a covert base, the country experienced serious tremors of the Vietnam War. By 1973, the US had reportedly dropped more bombs on Cambodia than they did during the entire World War 2. The US military terror was so severe that the entire population became involved in the struggle to capsize the US-backed king of Cambodia.

Meanwhile, American companies continued to earn a fortune in poor countries across the world. Intellectuals and students perceived the US as an enemy. And if US was the enemy, socialism and communism were professed as alternatives by many radical youngsters in Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos. Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh had become global inspirations.

On 17 April 1975, the Khmer Rouge dethroned the US-backed king and gained accolades from across the globe. Indirectly, the US superpower had been defeated.

Little did anyone predict that mayhem would be around the corner.

King Sihanouk, who was in charge before the US entered Cambodia, expected to be reinstated once the Khmer Rouge regained power. In fact, he had extended his support and helped them reach a stage where they could overthrow the US-backed king. But Sihanouk was soon put under house arrest by the Khmer Rouge, which, by then, had been taken over by Pol Pot.

As early as the second day after April 17, alarming reports started coming out. People living in the cities of Cambodia were forced to evacuate their homes and walk mile after mile along the blistering hot tracks to the countryside. Pol Pot, inspired by Mao Zedong from China, had started emulating 'The Great Leap Forward' in Cambodia.

Pol Pot built his army with the peasant class and persecuted the white-collar section of the society comprising of intellectuals, teachers, doctors and so on. The Khmer Rouge picked them up and brought them to the S21. The five buildings that tourists negotiate with the help of an audio guide tell the most horrific stories of torture and harassment at S21.

It is one of those rare places, which is crowded, yet quiet. Visitors struggle to gather their voice or get their heads around the cruelty that transpired four decades ago. Stunned faces meander through the rooms containing iron beds, to which prisoners were shackled. Every building is barricaded by iron bars and wires, which were introduced after a prisoner, in order to escape torture, jumped out of the window and sought refuge in death.

The five three-storied buildings at S21 face a courtyard with pull-up bars, green lawns and the epitaphs of some of the prisoners. The pull-up bars would be used for exercises when S21 was a school. The Khmer Rouge used them for the interrogation of prisoners. The ground floor classrooms are kept the way they were with iron beds, shackles and grisly photographs of prisoners mounted on the wall of each classroom. Bloated or decomposed bodies lying in pools of blood are common features in the pictures.

The prisoners were photographed and biographed upon their arrival - the oldest were in their late 20s and the youngest not even teenagers yet. Tags with their names and time of arrest were added before the process of dehumanization began. There are pictures of the prison staff dragging an inmate with a rope tied around his neck, like cattle. Another picture where a guard is holding a hose outside a room, in which a few prisoners have gathered, gives an idea of how they bathed. They were referred by their cell number and called ‘it’; not ‘he’ or ‘she’. Another building has thousands of such portraits made immediately after the arrests. One shirtless youngster is posing with the tag, which, on closer look reveals, is pinned to the boy’s chest muscle.

The elimination of intellectuals, teachers, doctors, or, for that matter, anyone who had a mind of their own, was part of the plan to create a society absolutely incapable of posing a challenge to the establishment. Knowledge of a foreign language or wearing specs were considered signs of being an intellectual. It resembles the narrative of George Orwell’s 1984, where the thought-police would be on their toes to nab anyone who had the potential to, basically, think.

Ironically, Pol Pot and Comrade Duch, who handled the daily conducts at S21, were both teachers before the Khmer Rouge assumed power in Cambodia.

The prisoners after being detained at S21 were tortured until they ‘confessed’ to their crimes. What the prisoner wrote on paper depended on what the interrogators wanted to read. There were rules of interrogation, which prohibited prisoners from crying during the electric shocks to which they were subjected to. They did not have the liberty to dispute the interrogator and any disobedience amounted to five electric shocks. Since the doctors too were on the hitlist, medics treated prisoners at S21. Bodies were opened alive to teach anatomy. Pouring salt water over open wounds was a regular practice. Prisoners, in their confession papers, ‘confessed’ to being spies of the West, supporters of the earlier regime, they implicated their innocent friends and what not.

A confession by one Koy Thourn titled “My Betrayal of Revolution” displayed at S21 implicates his grade 3 friend Eung Yunheang for “teaching me about People Movement Organization” and introducing him to one Hang Thonhak, who told him that Khmer Rouge is “against this entity” in 1953. Koy went on to work “as an informer in the Khmer Rouge” and later on “met a CIA chief”, to whom he “reported the activities of the Khmer Rouge”.

Once the interrogators received satisfactory confessions, the prisoners were killed. “To keep you is no gain, to lose you is no loss,” was one of Pol Pot’s slogans.

Close to 17000 people were detained here over the period of four years. Only 12 survived. One such survivor was Chum Mey, who, on the historic morning of April 17, 1975, had gleefully welcomed the Khmer Rouge with a white flag. But he soon had to follow orders and evacuate his house. He joined the exodus with his wife and children. His two-year-old son fell ill and died during the journey. The difference between Chum’s life and death, though, proved to be his skills on the sewing machine.

Chum believes he was allowed to live because he could fix sewing machines at the prison workshop. In October 1978, he was told he would be going to Vietnam to repair vehicles but he was, in reality, entering the darkest period of his life at S21. His tormentors ripped his toenails, broke his fingers, gave him 220-walt electric shocks for 12 consecutive days and nights in a cramped room of two metres by one metre where he lay blindfolded and shackled to the floor, sustained by the thoughts of his pregnant wife and the unborn baby.

In January 1979, the Vietnamese troops captured Phnom Penh from the Khmer Rouge and the prison guards fled along with some of the prisoners. Chum met his wife and his two-month-old kid in the provinces, where the prison guards had forced him to march at gunpoint. They were then ordered to walk into a paddy field where the prison staff shot his wife and the baby. Chum managed to escape and hid in a forest. He had two daughters as well, who disappeared while he was at S21. Chum’s memoirs are available for $10 at the museum.

In his ‘confession’, however, at S21, Chum eventually wrote he was working for the CIA and had recruited dozens of agents in Cambodia. He gave the names of his acquaintances, innocent men and women who, it is presumed, were later arrested, tortured and murdered.

S21 was a place where prisoners entered to never leave. Or only once. After having received satisfactory confessions at S21, the prisoners were shipped off half an hour away to the outskirts of the city in the serene orchard of Choeung Ek, better known as 'The Killing Fields'.

There are more than 300 Killing Fields in Cambodia but the Choeung Ek Genocidal Centre was the biggest one, where more than 20,000 people were executed in four years. This place was zeroed down upon by Pol Pot because it was out of the way and the Chinese were already using it as a graveyard.

Today, it is a memorial marked by a 17-level Buddhist Stupa constructed with glass walls to enable visitors to take a close look at more than 5000 human skulls recovered from the vicinity. The skulls, either smashed or shattered with huge cracks and holes, are merely an indication of the rampant brutality that engulfed the orchard for four years.

There are no structures at the Choeung Ek, for when the Vietnamese troops captured Phnom Penh, the ones living in the vicinity ransacked the place and used everything they could to prolong their survival amidst abject poverty and destitution. Every important spot surrounding the Stupa is marked with a sign board. Visitors, struggling to comprehend the history exhibited here matter of factly, walk along the edges of the exhumed pits, which remain open for viewing.

50-70 blindfolded, shivering prisoners ended up in these pits every two weeks for four years as a truck carrying them arrived at Choeung Ek from S21. On each killing day, a messenger would tally the number of arriving prisoners, so the authorities at Choeung Ek could dig the graves accordingly. Once the truck arrived, prisoners were taken straight to the ditches to be executed.

The prisoners were ordered to kneel and were clubbed on the back of the head with large pieces of wood. They were hacked to death with whatever was available, for bullets “were too expensive”. Soldiers of Khmer Rouge picked up newborn babies and kids and smashed their heads against walls and trees to kill them in front of their mothers. In order to avoid unnecessary outside attention, a generator would be left running to drown the screams and screeches of those being tortured and murdered. A “magic tree” today sits pretty in the vicinity with its branches extending its shadow on the tourists. Huge speakers would be attached to the tree, which played Chinese revolutionary songs. It was just another precautionary measure taken by the Khmer Rouge to drown out the cries of the victims.

Further, DDT would be sprinkled over the bodies after execution to eliminate the stench that could possibly raise suspicion and also to kill off any victims buried alive. Cambodians still offer regular prayers at mass graves, where bodies have been found without heads, where parts of brain and blood were found under the soil. 166 Khmer Rouge soldiers also died here. They were defectors and paid the price for being humanitarian.

From 1975-79, in four years of devastation, 1.7 million Cambodians lost their lives, through executions, deaths by starvation and diseases due to overwork. Pol Pot wanted to make Cambodia self-sufficient. He closed off the country, prohibited imports and exports. City dwellers were shipped off to rural areas and rural inhabitants forced to stitch a new beginning in urban centers as part of the emulation of 'The Great Leap Forward'. Modern agriculture equipment was left to rust and citizens were compelled to work physically. Many newborn kids died because mothers were not allowed to breastfeed them by sidelining physical work. Others could not endure the 180-degree change in their lifestyle. 1.7 million, or 20-25% of the country’s population, or a generation, obliterated within four years. While travelling through the country today, the conspicuous rarity of old men and women is striking, but not surprising.

In 2007, a tribunal was set up and some of the senior members of the Khmer Rouge were tried and then convicted in 2011. It was an attempt to extend some sort of a closure to the survivors whose lives were ruptured during the period. Pol Pot, however, died a natural death in 1998, without ever being brought to book.

The cloud of the catastrophe still hangs around Cambodia as people who endured the disastrous time are still recovering, attending counseling sessions, dealing with it in their own way. Every year, on May 20, Cambodians mark a 'Remembrance Day' and offer prayers at various memorials.

But the most remarkable feature of the two museums, and thereby of the country, is that they have not tried to suppress or spin the atrocities inflicted by their own people. On the contrary, their art, music, movies and paintings repeatedly talk about it. To strike a conversation about Pol Pot in Cambodia does not mean entering into a banned territory. Every high school student learns what happened and many of them do their best to pass on the information without being worried about being called an anti-national.

While the magnitude of the carnage may be impossible to emulate in a democratically elected republic with a robust constitution, the thought behind the Pol Pot atrocities is not too far from home. The Dadri incident springs to mind. A contempt for intellectuals is not alien to India either. A secular democracy may have prevented a Pol Pot to crop up, but whether it is 1975 or the discourse post 2014, the vile abuse and witch-hunt of intellectuals in India intersects every regime under an autocratic leader. The fact that the intellectuals have the ability to influence minds seems to tickle the insecurity of such leaders, who are constantly on the lookout for an opportunity to prove their power.

When actor Aamir Khan spoke out against the rising intolerance in India, he was pilloried for “defaming the image of India globally” by howling anchors and by those claiming to have the monopoly over nationalism. The writers involved in the Award wapsi were also blamed for sullying the image of India. It merely reflects the immaturity of the dialogue in a country that is otherwise aiming to compete with global giants.

The juxtaposition of discourses, sadly, only makes us look parochial and insecure in front of Cambodia, which may be poor, but is definitely mature. As one completes the tour of S21, the poignant voice of the audio guide, which is recorded by one of the 12 survivors, nears its conclusion. All along, I expected some sort of a positive spin towards the end. However, the audio guide concludes, “At the beginning of the tour, I told you the archives of the place are memories. As you leave the place, you too are the keepers of this memory. For us to strive for human dignity, peace and compassion everywhere today and in generations to come, go back and tell others what happened so the catastrophe is never repeated again.”

I just did.

![submenu-img]() Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour

Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour![submenu-img]() This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...

This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax

Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...

This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy

Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy![submenu-img]() Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’

Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’![submenu-img]() Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive

Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets

IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru![submenu-img]() Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral

Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour

Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww

Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww![submenu-img]() Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked

Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked![submenu-img]() This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why

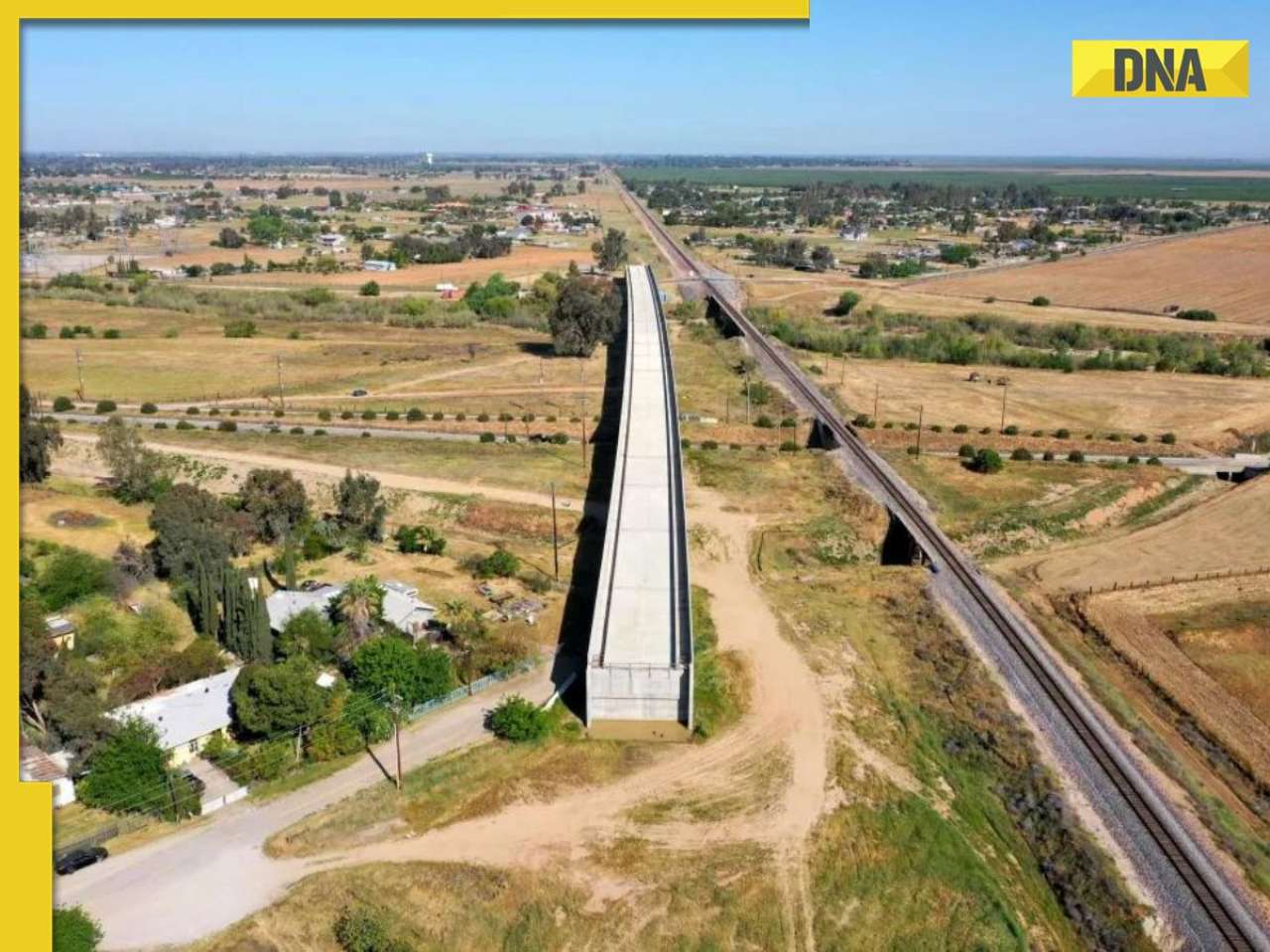

This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)