Fiction has only one form. True story, inevitably, has many, said VN Rao, in his oral narrative Questioning Ramayanas in 2001. India has often been held to the fractiousness of its own cultural diversity— ever since independence, the fault lines of religion, region, ethnicity, caste and class have strained at the conception of a national consciousness. India was considered to be too diverse to be united and too poor to be democratic.

While the exercise of Indian democracy has lasted well into 60 years, it cannot be denied that religion especially the secular stand of the Indian state and the rhetoric of Hinduism has continued to be politically tense in a country of over a billion people. The epic form of Ramayana is built around a moral structure of triumph over evil. It is not just an epic that transcends caste, religious and linguistic differences but also transitions into different cultural settings with characteristic fluidity.

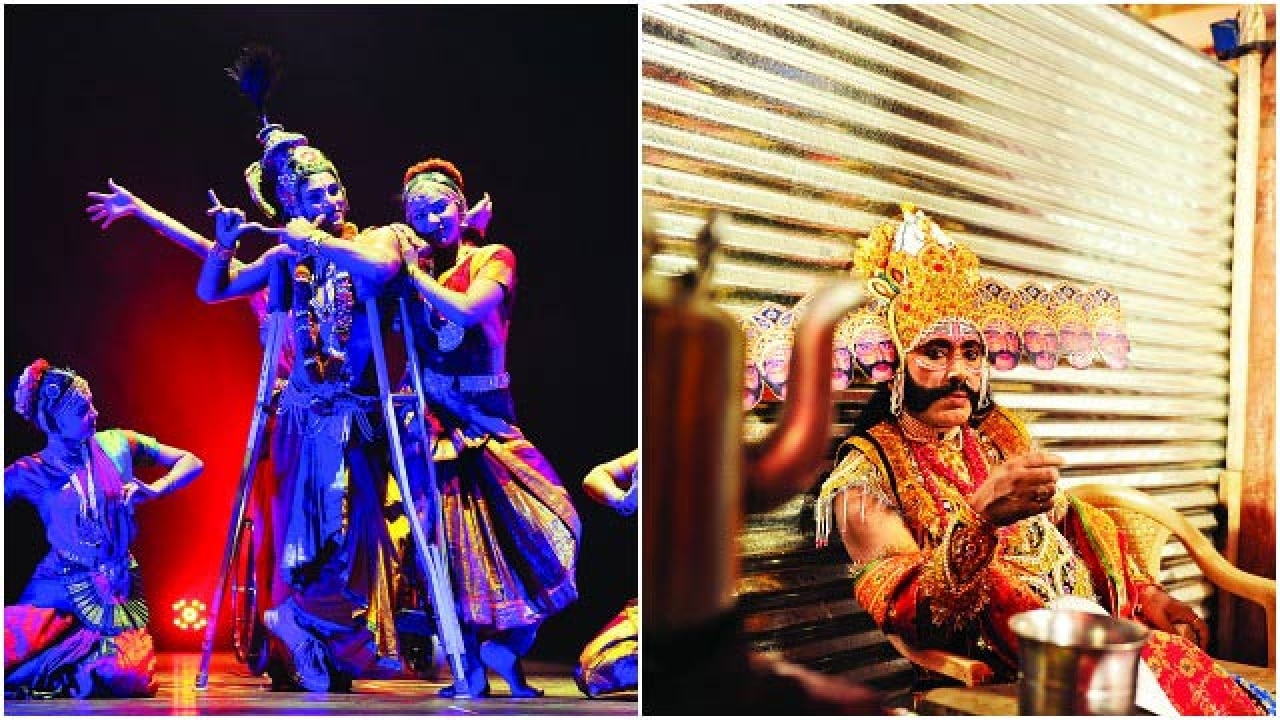

In West Bengal, the tradition of rod puppetry, also known as Daanger Putul Naach, draws on the Ramayana to form its content. The puppets are made to depict local cultural art forms: they are constructed and painted in the pata style of art, the enactment, style and content of puppetry is heavily inspired by the local theatrical tradition of the Jatra form and it is spoken in the language of rural Bengal. These performances are enacted on makeshift stages and can involve anywhere between 2-20 people, who control the puppets, deliver dialogues, play instruments and sing songs in a rich tradition of dramatisation seen in the local culture. A common story used in puppetry is that of Ravan, where his life predates the Ramayana by 2000 years and is based on the fight between Ravan and his brother, Kuber over the control of Lanka. The significance of this is not just in the lack of Ram or Sita’s stories but in the positive depiction of Ravan as the victor. This points to a decentralisation of the oral tradition that enables different stories that exist under a broad understanding of the epic.

In Kerala, the shadow puppet performance tradition is rooted in classical Tamil text expressed through the Malayali folk cultures, in it combining different cultural contexts to a common story. The puppet show tradition is more strongly allied with the religious space of a temple and is often conducted within or outside the temple. The mechanics are also quite different. Based on the Kampan’s text based on Valmiki’s Ramayana, Iramavataram, the puppetry is performed by three to five men behind a white cloth screen that captures the shadow. Verses from Kampan’s text are chanted and integrated with a personal commentary. The performances do not follow a linear storytelling but depict certain scenes such as Ram breaking the bow to win over Sita and the fight between Bali and Sugriva, which shows how Ramayana is was broken into many different stories, all having their own cultural life.

However, shadow puppetry in Kerala has hardly been able to attract a large audience. The nature of shadow puppetry places the performers behind the screen, physically separating them from the audience and uses an archaic form of the language. In Telegu Brahmin women’s depiction of the tale, the women are generally literate and adhere to strong traditional idea of femininity. They sing popular Ramayana songs in a group where most members do not have any musical training. Performances have female-oriented themes. In performing songs related to female issues, these women highlight the female characters in Ramayana as well as broaden the scope of largely male-dominated oral discourses based on Ramayana. For instance, one popular song describes the process of Kausalya’s labour and contains graphic details of the pain associated with it. Some songs allow the presence of male characters but mostly in female-dominated spaces- Ram is portrayed as the bridegroom in their wedding rituals but he clearly passive, and performs the rituals as directed by other women.

Ramayana is retold through different female perspectives and reinvigorates female characters, such as Santa, Dasaratha’s foster daughter or Urmila, Lakshman’s wife, who are marginalised in the mainstream literary accounts. The value of these songs is in highlighting the rich female histories embedded in Ramayana but lost in a mainstream telling.

The rich characterisation of this, for many audiences, is told and retold through its many characters. However, the cult of Ramayana has indeed transcended caste, class, demographic, linguistic and cultural divisions.