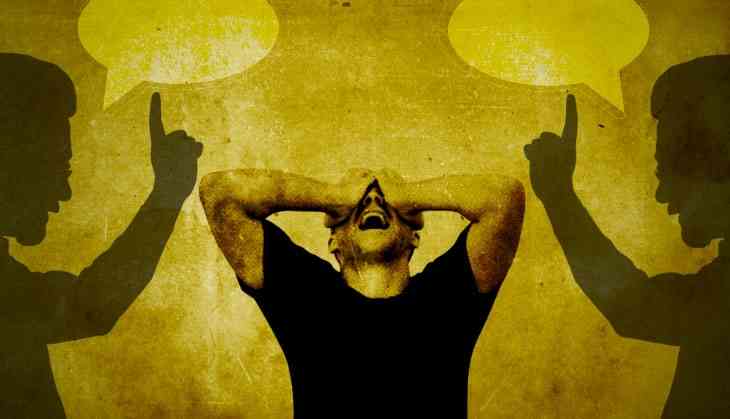

Yak Yak: The Indian Disease of Offering Unsolicited Advice (& Opinion)

That we Indians are fond of giving unsolicited advice is known. The Indian has an opinion on everything — which is fine — but she is not afraid to express it. That is a problem.

I welcomed the entry of social media into people’s lives. I thought to myself: What an incredible safety valve. Open your account and rant and rave on it all day and all night for all I care. Please don’t bother me.

It didn’t turn out the way I’d expected. There’s nothing that an Indian loves more than proffering advice one-on-one, like a therapist. Except that this person is not a therapist nor am I paying money in lieu of services rendered.

The Indian is convinced that he know things about people he doesn’t really know. A rapper from West Delhi called me the other day and explained to me what was wrong with Eminem’s life. The Subhash Nagar boy had the Detroit boy down pat. He ended the conversation with: “And now Marshall’s daughter will also get married and go away. He will be alone again.” But what would he know about Eminem’s daughter’s life plans? Even the tabloids have said nothing about it. And yet, the Indian knows.

The Indian has a lot of time on his hands. We find a job, marry and by thirty have kids. That’s the extent of our lives. Few develop interests outside their profession. Former players-turned-commentators go on commentating till the cows come home. Even legendary actors put on wigs and appear in commercials out of the habit of staying in the public eye. What would they do otherwise? Well, there are things that you can do but then you have to have a curious mind that gets interested in things.

With that not happening, we have plenty of time to kill. This spare time is filled up in offering advice to people. Twitter and FB is not enough. Nothing like grabbing someone by the collar and taking away an hour of his life.

***

An Indian will give advice to strangers on a train. The Indian is always giving advice to friends: This is the kind of girl you should marry; this is what your friend circle should look like; this is how much exercise you should be getting; this is the kind of book you should be writing. This is what is WRONG with your life. The advice-giver has it all figured out. Nothing is ever wrong with him/her.

In fact, the advice-giver is convinced that he knows things about you that you yourself don’t, including the essential facts of your existence. You say: “I was born in Bombay”. He will say: “No, no, you were born in Delhi”. You have to believe him. Or he will get upset.

The Indian doesn’t approve of your finding loopholes in his advice. The person giving the advice does not have a complete picture of the person he is giving the advice to. The advice-giver works out of partial knowledge. It’s inevitable that the person being given the advice is going to turn around and say: “But hold on. You might be wrong there.”

Nothing doing. The advice-giver will carry on regardless because he is convinced he has a solution to everything. The irony is that the provincial Indian giving advice is hyper- sensitive himself.

It’s a curiously Indian combination — that of a thick hide, which makes you impervious to subtle signals, blended with a hypersensitivity to what people say about you.

If you start judging the advice-giver and turn the advice tables so to speak, he will get upset and withdraw into a shell. His touchiness knows no bounds. If you start picking holes in his own personality he will take it personally. This is the reason why Indians are always going into long infantile sulks with each other. Since they are generally incapable of conversation, preferring only to speak from a pedestal, they get confused if someone stands up for herself. This is seen as an affront.

***

Indians also have high expectations of fellow Indians. And none of themselves. This is yet another aspect of our relentless advice-giving culture, a variation on the theme.

Sachin Tendulkar suffered this more than any other Indian. Rewind back to the time Sachin hadn’t got to his hundredth hundred. He’d scored ninety-nine centuries but that wasn’t enough. He’s been stuck at number ninety-nine for a while. Sachin himself spoke about the pressure, something he’d never felt to this extent at any point in his career. He said that wherever he went in India, everyone from the hotel doorman to the company CEO, only had one question: “When will the hundredth hundred come?” “Sachin, it’s not happening. Why did you do this and not that in the last test match?”

“Why don’t you...”, “But you should have...” or “But you haven’t...” is the way we start most conversations in India. Suppose you’re a first-time novelist who has been shortlisted for the Crossword prize. Then you don’t win. The Indian friend will say: “But you didn’t win the Crossword prize.” Then you write another novel and it wins the Crossword Prize. The Indian will say, “Crossword and all is fine but you haven’t won the DSC.” So you write another novel and win that medal. The Indian will now say: “But you haven’t won the Booker.”

Your next novel — you’ve become a really very prolific writer by now — goes on to win the Booker. At this point in your glittering career, the Indian will say: “But Salman Rushdie won the Booker of Bookers.” You say, fine, let me write some more novels. You do. You win the Booker of Bookers. The Indian will yawn, lean back and throw another one at you. “But, you know, you haven’t won the Nobel.” The Nobel, we know, is awarded for a lifetime’s achievement. So you write twenty more novels and become really old and are finally awarded the Nobel. You call this Indian friend who’d been hounding you all his life to say: “Look I did it you moron. Do you respect me now?” His wife picks up the phone and says in a heavy voice: “Didn’t you know he passed away because of a heart attack more than two years ago.”

That’s a Nobel, and a life, gone to waste.

(The writer is the author of Eunuch Park & The Butterfly Generation)

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)