The battle between faith and culture isn't new. Here's how Akbar reconciled them

The Mughal dynasty that ruled the Indian subcontinent in the 16th and 17th centuries left behind a great legacy of architecture, literature and cuisine. But they've often been accused of consolidating their empire by destroying temples, killing Hindus and forcing the 'kaafirs' to embrace Islam.

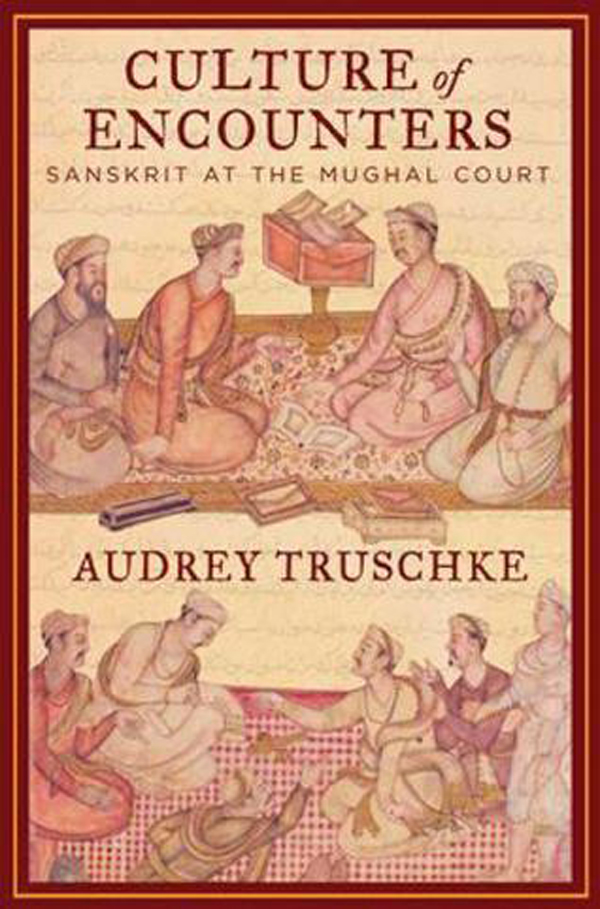

The line between fact and fiction has always been blurred. A recent book, Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court - tries to fill these gaps. And in the process, shed light on how the often polarised beliefs of the arts and religion can find peaceful coexistence.

Also read - Twitterati took #RemoveMughalsFromBooks and turned it on its head

Author Audrey Truschke details the 'awkward' moments Mughal Emperor Akbar encountered when he ordered the translation of the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata into Persian in 1580.

Truschke says the translation of the Bhagavad Gītā was truncated to "avoid devoting too much time to either Hindu or Islamic theology". She insists that this approach was to reach a cultural accommodation for a predominantly Islamic audience rather than being tied to any "calculated theological objectives".

She also cites an instance when Akbar was upset with Badāʾūnī, his most prolific translator, for introducing an Islamic notion into the text to prove his point.

The hurdles

Truschke describes the Razmnamah - the Mahabharata in Persian - as a "politically charged account of India's pre-Islamic past".

It became an important part of the curriculum of the royal princes. In fact, Akbar chose his brightest writers Fayz̤ī and Abū al-Faz̤l to help with the translations and is said to have never devoted similar resources to another translation.

Yet, it wasn't the easiest of tasks to translate the epic.

To recreate the Mahābhārata as an Indo-Persian epic, the Mughals used several techniques that made it "simultaneously foreign and familiar for an Indo-Islamic audience".

Also read - Ridiculously tolerant Twitterati wants to #RemoveMughalsFromBooks

Truschke says the translators preserved hundreds of Sanskrit words, transliterated into Perso-Arabic script and also employed Persian poetry throughout the prose. The problem, however, arose while incorporating the Islamic notion of monotheism in the narrative.

"This mottled approach results in an uneven religious landscape that lightly acculturates the story for an Islamicate audience while still introducing the Sanskrit epic's religious scaffolding," writes Truschke.

Truschke cites an example: "...at the opening of the Razmnāmah, Brahma is replaced by the Islamic God (khudāvand): 'When the sūtapūrānik [narrator, sūtapaurāṇika in Sanskrit] knew that Shaunaka and the others desired to hear this story, he began the tale. He first invoked the name of God, Great Be His Glory and Magnificent His Bounty [jalla jalālahu wa ʿamma nawālahu]'."

However, this was not an attempt to undermine the value of Hindu gods. Only a glimpse into the challenges the translators encountered to make the story relatable to a people with a monotheistic worldview.

For example, Truschke narrates the story of Nala and Damayanti to present the "blended religious landscape".

"In the Sanskrit text, Damayanti beseeches the scheming gods to desist from their deceit. But, in Persian, in the midst of Hindu deities who all look like Nala, Damayanti prays to 'God, the Exalted and Glorified' (khudā-yi ʿazz wa jall). She then calls upon God as 'O Solver of Obstacles and Guide for the Lost'."

The periodic incorporation of one all-powerful God likely rendered the Mahābhārata more accessible to readers, reconfirming Truschke's views about "acculturation" of the text for "for an Islamicate audience."

An uncomfortable message?

In a chapter titled "Many Persian Mahabharatas for Akbar", Truschke writes that "Mughals indicate discomfort with the perceived Hindu message of the Bhagavad Gītā by drastically shortening and altering this section".

In comparison with the 700 or so verses in Sanskrit, the Bhagavad Gītā occupies very few pages of the Razmnāmah. It seems that the Mughals wished to avoid the theological content of the Mahābhārata where possible, Truschke points out.

However, he also insists that this approach was to reach a sort of cultural middle ground for a predominantly Islamic audience rather than being tied to any "calculated theological objectives".

"Thus, they reframe an overly Hindu Bhagavad Gītā within a monotheistic framework while truncating the text to avoid devoting too much time to either Hindu or Islamic theology."

But despite this being an exercise in walking a cultural tightrope, the text avoids entirely new Islamic ideas.

In fact, Akbar was upset with Badāʾūnī, his most prolific translator, for introducing an Islamic notion - "Every action has its reward and every deed its recompense" - in the Mahabharata.

Akbar sent for him and said, "We imagined that this person [Badāʾūnī] was a young, unworldly adherent of Sufism, but he has turned out to be such a bigoted follower of Islamic law that no sword can slice the jugular vein of his bigotry."

Truschke writes that according to Badauni, Akbar objected to the use of this verse because of its reference to the Day of Judgment. But Badauni successfully convinced Akbar of his faithfulness to the text, and the line remained unchanged in the Razmnāmah.

The translators

The initial Mughal version of the Mahabharata drew from Sanskrit and Persian intellectuals and nobody involved in the project knew both languages - as a result of which two teams of translators were assembled.

On the Persian side, Naqib Khān led the effort. He was assisted by Mullā Shīrī, Sultan Thānīsarī and Badauni. Amongst the Sanskrit scholars were Brahmans - such as Deva Misra, Satavadhana, Madhusūdana Misra, Caturbhuja, and Shaykh Bhāvan.

In the translations, several Sanskrit words were retained even though Urdu/Persian equivalents were available. The word naraka (hell) could have been reframed as duzakh, and puraṇa (history) as tarikh - but the Sanskrit words still found their way into the Persian version.

The point to ponder over is this - despite its flaws or imperfections, there was still a conscious effort to retain the core essence of a "Hindu" text. Akbar, in his time, did his best to preserve Indo-Persian culture. Can we then not preserve their history, and allow them to remain in our textbooks?

More in Catch - Here's why Smriti Irani should make Indian history lessons compulsory for Sangh's online brigadeWhat Bahadur Shah Zafar did on his last day as Mughal Emperor

First published: 16 May 2016, 23:56 IST

_251049_300x172.jpg)

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)