Relaxed, smiling, caressing a dictionary: How I remember Tom Alter

One really has to stretch things before Tom Alter’s connection to the British Isles is established. He ended up being every Indian Film Director’s Englishman, including the illustrious Satyajit Ray.

Tom was in fact the son and grandson of Christian Presbyterian Missionaries from the United States of America who came to India in 1916 and made it their home; not unlike Samuel Stokes who also came to India to work among those suffering from Leprosy and was also to marry, settle down and live in India.

Two generations of Hindustani film audiences have grown up watching and listening to Tom Alter, from Charas in 1976 to Sargoshiyan in 2017 and in scores of other films. But most have no idea that the pidgin Hindustani he was made to speak was not only a caricature, that we have chosen to believe of the way Englishmen spoke Hindustani, but was also far removed from the way Tom himself spoke, Urdu and Hindi.

We, who take great umbrage at being caricatured in foreign cinema and are ready to set fire to cinema halls showing such films, have endlessly caricatured the English, especially the way they spoke Urdu and Hindustani.

In most of the films that Tom acted in, he was made to speak in the manner we imagine our colonial masters spoke and this despite the fact that there were many among them who did scholarly work not only in Persian and Urdu but also in many other Indian languages.

The one time English Principal of the famous Delhi College was an Urdu Poet and a disciple of Ghalib and one of the finest dictionaries of Urdu was compiled by an Englishman. And yet in all Hindustani Cinema, every British Man living and working in India, spoke a strange creole; and in many of them it fell to Tom to mouth this pidgin Hindustani.

It is a tragedy that Tom who spoke better Hindi and Urdu than many of those who strut across the silver screen was asked endlessly to mouth this patois.

I, like many others in their college and university days, first saw Tom Alter in the Shyam Benegal Film Junoon. Incidentally the film is not even mentioned in Wikipedia and the HT as one of the films Tom acted in. I thought of Tom as a very fine actor who was doomed to play the Gora Saheb, because of his diction. I narrate this because this has a bearing on how I first met Tom.

I had conceptualised, researched and scripted a film, Urdu Hai Jiska Naam, on the History of Urdu, the film was directed by Subhash Kapoor and produced for the Ministry of External affairs by Kamna Prasad. We had finished shooting for the film and were trying to find an anchor /narrator for the film.

I had met both Farouq Sheikh and Naseeruddin Shah earlier and I approached them with the script one after the other, both liked the concept and script and agreed to anchor it, but both were busy for the next few months, Farouq had to attend to some encroachments on his farm in Gujarat and Naseeruddin Shah was scheduled to leave for the United States for the shooting of a film.

So here we were, with a deadline hanging over our heads and no anchor.

Two days after our meeting Naseer Saheb in the green room of an auditorium at the Ashoka Hotel where he was rehersing for a performance, I saw an episode of “Jeena Isika Naam Hai” -- a TV serial about celebrities that was anchored by Farouq Sheikh.

In this episode, where he was talking to Naseeruddin Shah, Tom was to be a surprise guest. He could not reach due to some other commitment, so he sent a video, Naseer and Tom were at the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune together and Tom talked about those times and the formation of the Motley Theatre Group in Bombay.

This was the first time that I head heard Tom speak Urdu. What a vocabulary, what diction, what delivery and a sense of being freed from tension or 'sukoon' that he communicated.

I sat there mouth open, the moment the programme finished I rang up Subhash Kapoor and told him what I had just seen and said to him, let us try to get Tom’s email. We got it after calling a few friends in Bombay, I sent him the script with a request that he anchor the four-part series.

He replied next morning, saying he was coming to Delhi for three days for a performance and would stay at the India International Centre (IIC). Then he would have to go to Musoorie for two days and could stay back for three days for the shoot once he returned from Musoorie. He suggested we meet at IIC for breakfast the day he arrives.

So that was that. Subhash and I met him, we told him we had very little money and could not afford his fees but could he please do it for whatever we could put together, He said “I am not doing it for the money, I am doing it for Urdu, I owe it to Her”.

And so over the next three days, we shot all over Historic Delhi. The then Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India, Mrs Kasturi Gupta Menon, permited us to shoot at all monuments protected by the Archaeological Survey of India, and we shot from sunrise to sunset.

Tom kept working on his lines between breaks and shifting locations. Rarely did we have to retake a shot for him fumbling. The sound of a plane, a car horn or something technical would lead to retakes; or when Tom himself wanted one, unhappy with the way a phrase had come through or because he thought that he should not have paused where he did.

Almost all the shooting was in the sun but Tom never said a word about how the harsh sun bothered him.

The film was made in an English and a Hindustani version so he had to switch between English and Hindustani for each Anchor piece and he did it with great felicity and ease, without mix-ups and without stumbling over long anchor pieces.

***

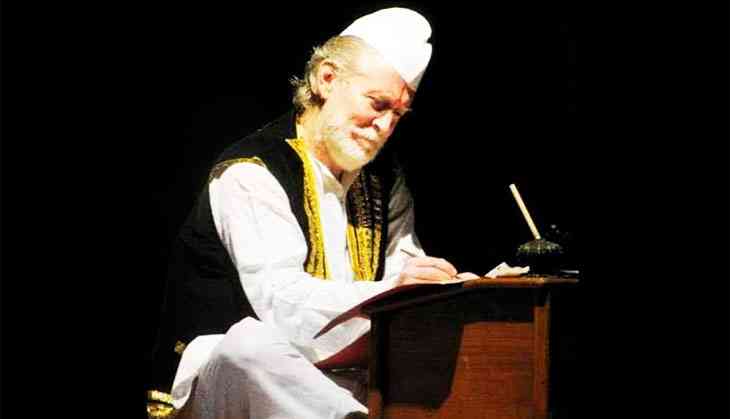

When we first met Tom he had come to perform in a play directed by Dr Syed Alam. His association with the Dr Alam was to lead to some of most memorable roles by Tom in theatre - Ghalib and Abul Kalam Azad - the latter almost a Soliloquy lasting nearly three hours.

I learnt little things about Tom while talking to him over meals: he ate very little, did not drink and was a vegetarian, at least this is the impression I have, unless he was off meat while we were shooting. Salads, fruits, honey and tea with an occasional toast was all that he ate.

We talked as he nibbled at his meagre victuals and I learnt that his father had insisted that he learn Urdu and Persian. While still at Woodstock School, a teacher came home to teach him the two languages for several years. Tom kept up with his readings later as well.

One day, while he was in Delhi in connection with the performance of one of Dr Alam’s plays, we met for breakfast. We were talking about problems of translating from Urdu, Hindi and Hindustani into English.

I mentioned the 1884-published Urdu, Hindi, Hindustani-to-English dictionary compiled by John T. Platts as a dictionary that was still the best. Tom said there were two books that he always carried with him: the Holy Bible and Platts' dictionary. He then said how once, in a rush to catch a flight, he left the dictionary -- a gift from his father -- in a hotel room. He rang up the hotel the moment he realised that he had left the dictionary behind, but it wasn’t found and he missed it dearly.

I told him that the dictionary had been reprinted a few years ago at the initiative of Anis Azmi, an old friend from theatre and secretary of Urdu Academy Delhi. “Let me see if I can get you a copy,” I said and rang up Anis, only to be told that all copies had been sold out except for a couple with damaged binding. Tom said he wanted the dictionary, not the binding.

Next day I gave him the dictionary, with the hard cover broken from a corner. A sense of great joy and relief seemed to envelop Tom. That was perhaps our last meeting and that is how I would always remember him, relaxed, smiling quietly, absentmindedly caressing the spine of the Dictionary.

Edited by Joyjeet Das

_251049_300x172.jpg)

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)