The state too is to blame

Ever since Justice TS Thakur took over as CJI in December 2015, he has been preparing his staff and colleagues for the tasks ahead and hoping to get cooperation from other stakeholders: the central and state governments as well as the lawyers.

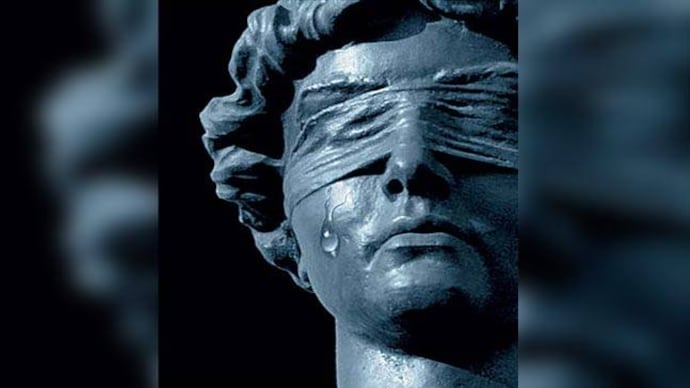

It was sad to see the Chief Justice of India (CJI) make an emotional appeal to the prime minister at a joint conference of chief ministers and high court chief justices in Delhi on April 25. The CJI broke down, bemoaning the lack of sufficient number of judges to handle the avalanche of litigation.

One can understand his predicament. Ever since Justice TS Thakur took over as CJI in December 2015, he has been preparing his staff and colleagues for the tasks ahead and hoping to get cooperation from other stakeholders: the central and state governments as well as the lawyers.

Unfortunately, the central government is yet to recover from the stinging rejection of the NJAC Act by the judiciary, restoring the much-maligned collegium system of appointing judges. It is not easy to get the revised memorandum of procedures approved by both sides and the process is likely to generate hiccups in the future as well.

The CJI mentioned two more factors behind the delay: lawyers' refusal to give up their vacations to speed up cases, and the reluctance of states, under whom the subordinate judiciary functions, to do anything to increase the number of courts and judges, as desired by the Supreme Court in its 2005 judgement. For many of them, the judiciary is not a revenue-generating department and, hence, a low priority for investment.

In a recent meeting of the National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms of the Government of India, it was revealed that there was a steady decrease in capital expenditure by many states in the last 3-4 years on court administration. At the same time, some of the states collected, by way of court fee and fines, double the amount of their capex investment. One state had invested just Rs 4 crore in one year, but collected, through administration of justice, Rs 203 crore. If the information is revealed to the litigant public, they will take the fight against their respective state governments and spare the CJI from the sordid task of convincing politicians again and again.

While an increase in the number of courts and judges is a desirable solution, the systems and sub-systems in judiciary contribute to avoidable delay and have not received the attention they deserve, either from the executive or the judiciary. Delay is inherent in the adversarial model of litigation, as structured by the Civil Procedure Court, the Criminal Procedure Code and the Evidence Act.

Many countries thus have opted for non-adversarial systems of dispute resolution and diverted cases for negotiated settlements without trial. Though India amended its laws to divert civil cases for mediated settlements and criminal cases for plea bargained disposals about 10 years ago, no headway has been made to reduce cases listed for regular trials. Judges and lawyers alone are responsible for this. Clearly, we operate a 21st century system with 20th century structures and a 19th century mindset.

Consider the family courts, the juvenile justice boards and the gram nyayalayas-specialised courts supposed to resolve disputes expeditiously, through non-adversarial adjudication and minus procedure and evidence technicalities. Parliament has gone to the extent of excluding appearance by lawyers. Yet most are buried under unresolved cases, forcing the poor to litigate in regular courts.

When resources are limited, work is organised according to priorities and on principles of management. But with the judiciary, old cases are allowed to become older while newly filed cases are taken up. Judges trained in one jurisdiction are transferred to jurisdictions they are poorly-equipped in. They are burdened with administrative responsibility, sacrificing judicial time and court work.

Intelligent management of courts and cases requires credible, updated data on status of docket and stage of proceeding, almost on a daily basis. This task can hardly be addressed without modern technology. While some courts are moving in that direction, many others continue without technological support in management of systems.

One major issue causing delay, which politicians and judges avoid talking about, is the reform of the Bar. Organised like a pyramid, 'superstar' lawyers monopolise all well-paid litigation at the top and refuse to cooperate with courts, as their presence is required in multiple courts at the same time. They seek adjournments, by means fair and foul, and cause delay. Even when they can manage through written advocacy, they avoid doing so-possibly to please clients and justify the huge fees they charge. The Bar Councils, which can discipline lawyers, are either indifferent to the malaise or participate in the loot themselves. And the government has taken no steps to amend the Advocates Act, to ensure competence and professionalism.

The CJI is right: it's not just the judges. The government and lawyers are no less responsible for our crumbling edifice of justice.

The author is founder VC, NLSIU, Bangalore, and NUJS, Kolkata

Also read:

CJI Thakur makes emotional appeal to PM Modi, calls for increasing judge strength