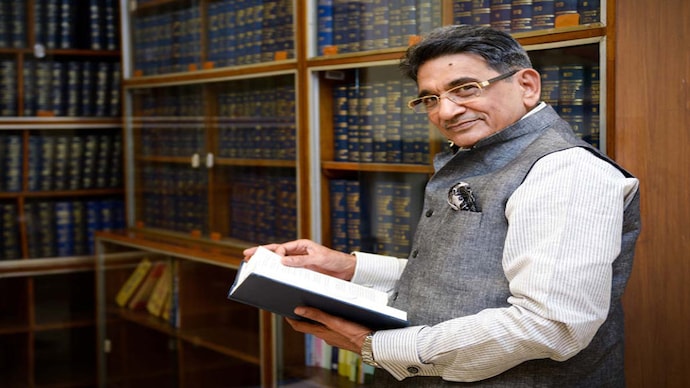

CJI Lodha: Those talking of corruption in the judiciary are themselves involved in corruption

A staunch defender of the collegium system of judicial appointments, Justice Rajendra Mal Lodha was one of its first beneficiaries in 1994, when his career as a judge took off.

On September 19, Justice Rajendra Mal Lodha is relaxing on a settee in his Krishna Menon Marg bungalow. It's exactly a week before the five-month term of the 41st Chief Justice of India (CJI) draws to a close on September 27. His manner is more cheerful than formal. It's hard to imagine that just a few hours ago, he had severely upbraided CBI Director Ranjit Sinha's counsel for raising his voice at the Supreme Court and "exceeding limits". Court insiders know that behind his genial exterior lies a core of steel. His low baritone can suddenly turn into a boom, especially when the independence of the judiciary is at stake. A staunch defender of the collegium system of judicial appointments, he was one of its first beneficiaries in 1994, when his career as a judge took off. The collegium system has now come full circle, as the National Judicial Appointments Commission waits in the wings, just as his 21-year-old career as a judge. Justice Lodha in conversation with Deputy Editor Damayanti Datta on the future of the judiciary:

Q. How much courage does a judge need?

A. You have to have very firm moral values. And you know those must be consistently followed. You can't practice those today because they suit you and then discard them tomorrow because they don't suit you anymore.

Q. Was there a time you felt defeated by the system?

A. A pet plan of mine was to keep the courts open 365 days a year, leave aside a few holidays. I have not been able to get it through. That's a big setback. Time has come when we have to have out-of-the-box ideas. It was perfectly workable. It would have given young, talented lawyers who do not get much chance some work. Some solution could have been found. But, unfortunately, that did not happen.

Q. Under you the judiciary and the executive nearly clashed, something that was building up since the days of CJI SH Kapadia. How do you explain this?

A. No, no. I am very proud to say we have a wonderful Constitution and I always wish that all the three organs, the Parliament, the executive and the judiciary, must remain strong. They are the temples of democracy. I don't agree that there were clashes.

Q. You have called the CBI a "caged parrot", asked thenattorney general Goolam Vahanvati not to complain because judiciary challenging government policy "happens in a democracy" and criticised the Government over the Gopal Subramanium episode...

A. If I am doing something, it's because the Constitution requires me to do so. That's the oath I have taken: to uphold the laws. If I am working within that, the other two organs must not feel that I am clashing with them. If the court strikes down a law, you don't see it as a clash if you have respect for democratic institutions. The interpretation of laws is up to the judiciary, what the law should be is Parliament's business.

About Gopal, I don't know what made him withdraw his candidature for appointment as a Supreme Court judge. I was not in the country. Perhaps he had some misgiving, perhaps he did not understand the thing properly. But he knows the system, the role of the government and the judiciary. I don't know. That was again a sad, sad chapter.

Q. There's a feeling that the judiciary is getting into everything. How would you respond?

A. We don't get into everything, we go only where we find constitutional violations. A matter may appear purely to be in the executive domain but that may not be so. Wherever there is constitutional and legal infraction, the judiciary just can't shut its eyes. It is its primary duty to see that the Constitution is followed and the law is observed.

The balance of power between the three organs is very nuanced. There is a very fine understanding. Say, the disaster in Jammu and Kashmir. For the common man, relief, rehabilitation and rescue are the government's job. So you may ask, why does the judiciary poke its nose? But the judiciary's role comes into play if food, water or shelter are not made available to a citizen, because then it's a violation of human rights. This is where the court's role comes in.

The Indian judiciary is very mature. It understands its role. If it's a pure policy matter, which has nothing to do with constitutional flavour, the court will never touch it. But what happens is that the line is invisible. One feels it's an act of judicial activism and that the judiciary has taken upon itself the role of the executive. If seen deeper, it would not be so.

Q. The judiciary often gets into economic decisions and then there are consequences. Is the judiciary losing touch with reality by not allowing the country to do business?

A. Every economic decision, more so on natural resources, has to be in consonance with constitutional norms and principles. If there is wholesale violation of those, the consequences may be serious. They may directly or indirectly affect the economy. Look, the court takes all aspects into consideration, always tries to strike a balance. But when there are gross illegalities and constitutional violations, then perhaps the court needs to step in.

Q. You have been a defender of the collegium system. At the same time, you have said that the judiciary should be transparent. How can the two go together?

A. The two are not mutually exclusive. When I became the Chief Justice, I wrote to all chief justices of high courts, expanding the consultative process. I asked them to include the opinions of two more judges and two more lawyers of impeccable integrity. This could have been done. If you involve all stakeholders in the system, that can bring in transparency.

Q. What is your idea of a perfect appointment system for the judges?

A. This summer I went to England and discussed in detail their processes with the Lord Chief Justice. They, too, have a judicial appointments commission. But it is very different. They have a judicial commission of 15 people. The chairperson is a regular citizen. Five to six members of the commission are not connected with law: they are academics, businessmen, economists or social activists. Just two-three are from the judiciary, two are from the Bar. And they advertise for the posts. Initially good lawyers did not apply. Now, after five years, things are changing. They get full information on every applicant, hold interviews, discuss to see how much objectivity a person has, what his/her social orientation is. No system is perfect, no system is bad. Ultimately everything depends on who mans the system. If you have objective selectors who are determined to select the best, then it is not difficult at all.

Q. No politicians?

A. No politicians. But just see the contrast. I met a judge from Switzerland. He told me that one of the main eligibility criterion for judges in their country is that he must have some political affiliation. But he also said no judge till date, once he became a judge, has shown political bias or consideration. What a mature system! On the contrary, look at South Africa. They, too, have a service appointments commission for judges. But there things have not gone right.

So what can ensure the best choice of judges?

A. You must establish norms. And those must be strictly adhered to. For instance, if you are considering a lawyer, he must have conducted at least 100 cases in the last five years to be eligible for the post of a judge. This must not be compromised. We have systems in place, even in the collegium, but problems appear because ours is a diverse country where we have not been able to achieve diversity. You won't find all sections represented. Women, for instance, are under-represented. So if you find one who has less practice but you get a feedback that she is competent and honest and she could deliver, then you try to pick her. But then you are departing from the norms. In 10 years, you will have wonderful representation of women. Girls are doing very well: in every state, about 40-50 per cent of judges are girls. And they are doing extremely well.

Q. What is your yardstick for picking someone to become a judge?

A. A hundred cases in five years, a particular number of which must have been reported in legal journals, apart from his legal approach and understanding of law. Age is another issue: presently the cut-off age is 45. That needs to change.

Q. You have said that we have to be uncompromising as far as corruption in the judiciary goes. But how?

A. There is no place for corruption in the judiciary. This is a divine duty that has been bestowed on you. God could have made you a cobbler, an engineer, a dacoit, but God thought here is a person who I can trust to discharge my duty. So corruption has no place. I always say, if you want to make money, then for God's sake don't come to the judiciary. There are many other avenues.

Q. But there is corruption in the judiciary...

A. Yes, there is corruption. I cannot deny it.

Q. What's the way out?

A. Take action as and when evidence comes in. The Bar has to be vigilant. The problem is, people who are talking of corruption in the judiciary are themselves involved in corruption. That's the whole problem. Corruption can't be done with just one hand. This is a challenge, more so in the judiciary, because it is unacceptable in the justice system.

Q. When Justice Markandey Katju wrote about judicial corruption, you said the image of the judiciary is getting tarnished. Is it just a problem of image?

A. If something is wrong, nobody would say it should be kept under the carpet. But then if you have evidence, if you know about something going wrong, if you know about a person who's committing wrong, then you must bring that aspect, that wrong immediately to the notice of the people concerned. If I say today that I found this and this at Bombay High Court in 2002, I am not helping anyone's cause. Whatever you know, you must bring out immediately. Then, if something is not done, you can point a finger. If you keep quiet because you think this is not the right time to bring out such things, then you have not really helped the cause.

Q. There have been so many allegations against some of your predecessors?

A. I won't comment. Look, the system is there... The system can always be improved if you think there are deficiencies.

Q. What sort of support does the judiciary get?

A. The judiciary, by its very character, is not interested in support or lack of support. Our work is such that we cannot please everyone all the time. We are not very concerned with support. Yes, we want justice to be delivered expeditiously and, of course, qualitatively. Our budget allocation is made by the government. And everybody knows that's not enough.

Q. What, to you, is the biggest challenge before the judiciary?

A. The criminal justice system is not at all working the way it should. Civil litigation is almost stagnant. Go to a court and you will find a magistrate is required to deal with 100 cases, 20-30 trials, with over 10 witnesses in each. Ultimately he can only pay attention to five or six such cases. Human limitations compel the magistrate to adjourn 60 per cent of the cases. Even if a lawyer wants adjournment without reason, he would say 'yes' and not ask 'why'. This compounds the problem.

The Chief Justice of England said they deal with 150 cases a year. I said, "Lord President, please come to my court." On any Monday or Friday, we have 800-850 cases listed in all our 12-13 benches. Each bench deals with 60-65 matters a day. Each judge does 2,000 cases a year. But then, you can't have a Supreme Court that is too big and unwieldy. The top court has to be compact.

In America, there are 75 judges per million people and we have 13, the lowest in the world. The judge-case ratio is also terribly skewed, with 30 million cases pending across the country, 65,000 in the Supreme Court. Germany is a civil law country: they have several Supreme Courts, dealing with different types of cases. They are stunned when they hear that our courts deal with everything-civil, criminal, environmental and constitutional matters.

To read more, get your copy of India Today here.