An obsession with the wild west compelled then mayor Steve Reed to scour the country for artefacts and plan for a museum to house them all in the unlikely location of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

The museum never came close to being built, and on Monday prosecutors and Reed’s lawyers will begin to pick a jury for the former mayor’s trial on 112 counts of receiving stolen property.

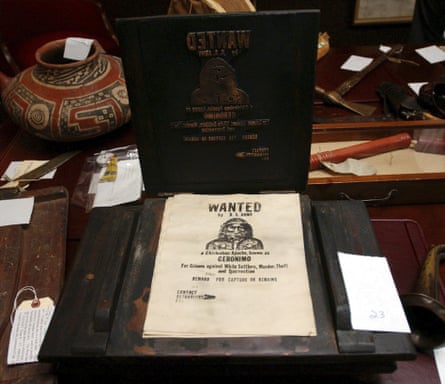

Investigators say they recovered some 1,800 artefacts, many from Reed’s home, and jurors will hear about dozens of them. They include stagecoach equipment, saddles, a dice game known as chuck-a-luck, copies of the Tombstone Epitaph newspaper, knives and a gun collection that includes a weapon once owned by Wyatt Earp and a “Whorehouse Box w/pin fire revolver”.

Reed’s lawyer, Henry Hockeimer Jr, said his client, who is dealing with what he described as serious health issues, denies the allegations.

“Suffice to say that we believe the evidence at trial will show that Mr Reed … did not steal anything and was in fact in lawful possession of the items the attorney general’s office charged him with,” Hockeimer said.

As to why Reed is charged with receiving stolen property, as opposed to theft, Hockeimer said prosecutors “never have completely articulated their theory”.

Reed, a Democrat, had won re-election six times and received plaudits for revitalising dingy downtown Harrisburg. A centrepiece of his economic development strategy was a planned network of museums to draw tourists, including a civil war museum that did get built.

The wild west museum was clearly his pet project, an effort he continued to push even after it became public and attracted derision and pointed questions about the costs, which were paid by a city fund that Reed controlled.

A grand jury report issued nearly two years ago described Reed’s compulsion to buy artefacts as “an almost pathological preoccupation”.

A former spokesman for Reed, Randy King, told the grand jury Reed would send so many boxes back from buying trips they would sometimes clog the mayor’s office, making it difficult for city employees to move.

King testified that city officials tried to stop Reed, telling him: “‘You’ve got to stop this, you’ve got to cut it out, it’s just going to kill your career,’ but said Reed would not listen, the grand jury wrote. “He would simply repeat to them that he was ‘almost finished’.”

Reed’s museum plan had its supporters: as the scandal became public in 2003, a member of the board that oversaw the spending described him as “the Walt Disney of our time in central Pennsylvania”.

But by the next year Reed had to put the project on ice. Harrisburg was starting to stagger under the weight of hundreds of millions in Reed-era debt tied to a trash incinerator, a financial crisis that nearly bankrupted the Pennsylvania capital.

The wild west museum and artefact buying sprees were among the reasons Reed lost in the 2009 Democratic primary to one of his main critics, Linda Thompson. The city subsequently became the first Pennsylvania municipality to be taken over by the state.

Prosecutors have argued that Reed, 67, overpaid for many of the relics and collectibles. Under Thompson the city sold thousands of them, recovering about $4.4m of the estimated $8.3m the city paid for about 10,000 items. Experts said the collection had real treasures alongside fakes and junk.

A state investigator said a storage facility Reed maintained near his Harrisburg home was packed with artefacts and collectibles, as well as a recreation of his mayoral office, complete with civic awards.

“That’s one of many instances of poetic licence taken by the attorney general’s office in the drafting of the presentment,” Hockeimer said. “It’s not fair, it’s not correct.”

In May, a judge threw out 305 of the 449 counts filed against Reed, saying too much time had elapsed and the statutes of limitations had run. Prosecutors subsequently narrowed their case to 114 counts.

Reed is also charged with one count of evidence tampering for trying to sell some of the artefacts on consignment, and one count of dealing in the proceeds of unlawful activities.

Reed’s lawyers have tried to prevent prosecutors from using witness testimony of an appraiser, and to be able to tell jurors about the hundreds of charges that were previously dismissed.

“The commonwealth did not bother to take any steps to evaluate whether the city of Harrisburg disposed of the property it is alleging Mr Reed had stolen,” his lawyers argued in a recent filing. The attorney general’s office called that “an incorrect recitation of the process”.

The trial is expected to take about a week and a half.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion