In his painting The Colony Room I, Michael Andrews pays homage to two giants of British art. You can’t miss them. One is a short, orange-haired figure in a bomber jacket turned away from us with his paunch spilling out of his trousers. This is unmistakably Francis Bacon. “Champagne for my real friends, real pain for my sham friends!” the gutter genius is no doubt declaiming, as was his wont. From the group around him, a keen angular face stares out of the painting – and you sense with discomfort that you are being sized up by the all-seeing eyes of Lucian Freud.

It might seem dangerous to open a Michael Andrews exhibition in this way, given the artist often gets dismissed as one of the so-called School of London painters who worked in the shadow of Freud and Bacon. And this work isn’t just a reminder of their fierce glamour – other Soho bohemians mill around in this louche history painting, too. So is Andrews just part of that crowd, an interesting bit player in the story of modern British art?

Perhaps, at the end of the 1950s, he was, having just turned 30 (he was born in 1928). Yet this beguiling exhibition at the Gagosian in London takes us on a hot-air balloon ride far from the madding Colony Room crowd, into realms of quietness and vastness where he truly found himself as an artist. It is the rare kind of show that changes a reputation for ever. By hunting down a dazzling array of his very best paintings and displaying them in perfect light with plenty of space, the Gagosian is doing what a public gallery should have done by now: proving that Andrews, who died in 1995, is the poetic equal of Bacon and Freud.

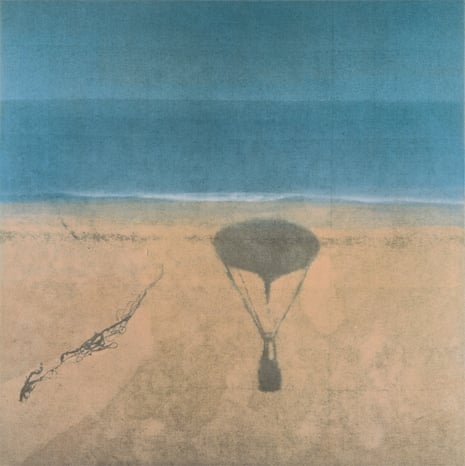

I recently met the owner of his masterpiece Lights VII: A Shadow (1974) at a party. Lucky bastard, I said. This painting has haunted me ever since I was a teenager, when I knew it as the cover image of The Penguin Book of Contemporary Poetry, published in 1982. The book’s designer made a brilliant choice – because this is painting as post-modern poetry. The shadow of a hot air balloon is moving gently across a beach. Painted in flickering yet precise detail, the dark image cast onto bright sand is beautifully real, but it’s not real at all. It is merely a shadow.

To paint an object just by its shadow recalls the ancient philosopher Plato’s claim that we are like prisoners in a cave where a fire burns, seeing not real things but only their shadows on the wall. Andrews seems to be saying that art too is just a shadow, a secondary glimpse of a life elsewhere. When you look at the painting in its opulent frame, you realise that reality is failing in other ways, too. For the great turquoise expanse of sea that laps the beach is not quite in perspective: what at first seems to be a literal depiction looks, on second glance, more like two expanses of abstract colour, blue over sandy yellow. It could be a Mark Rothko abstraction but for the shadow of the balloon. That shadow is all that makes this moment real.

Who is in the balloon? In other paintings in the Lights series, we see the actual balloon, but it is just as elusive, just as coolly distant. In one, a black balloon passes over the Thames by night in an echo of Whistler’s Nocturnes. In another, a yellow balloon glides above the soft green English countryside in summer.

Gradually you realise why these paintings are so eerily tentative and dreamlike. They are done with a spraygun. Today, sprayguns are often associated with in-your-face street art, yet in the 1970s Andrews began mixing acrylics and water in a spraygun to create landscapes of a Japanese delicacy. His visions of countryside passed over on a hot summer day, or seen from such a high viewpoint he might be in a balloon’s basket himself, have a frozen wonder that makes me hear pastoral psychedelia. Were some of these used as 1970s album covers? No, but they should have been.

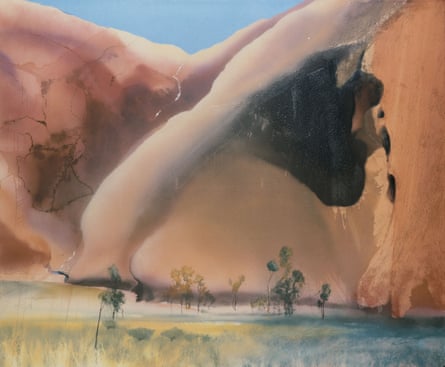

Andrews’ art may ache with alienation but it glows with awe. In Australia, he found landscapes so strange and colossal that, to question the very foundations of reality, all he had to do was paint them. The vast rocks of the Olgas and Uluru rise up in spray-painted stains of redness, marked with black holes of caves and swirls of vegetation, above trees that look like they are melting in the heat.

These huge paintings do justice to nature at its wildest in a way that bears comparison with Turner – yet the geology they reveal, under an empty blue sky, is so bizarre it mocks the very act of representing. Andrews does what all the School of London artists in postwar Britain were trained to do: he just paints what he sees. And the result leads us to doubt our own eyes, as the ochre masses of Australia’s rocks turn into abstract shapes, coloured stains.

There is something rare and enigmatic happening in Andrews’ art. From 1970 onwards, he appears to withdraw from the crowd, to stand back from the world. The spraygun method he used perfectly mirrors his decision to abandon portraits for landscape, for it removes his direct physical touch from the painting surface. He is not pressing a brush down, not making his mark. The paintings appear to be made passively, in a reverie. They well up out of the light and shadow. Looking at the world from far away, with a mystical scepticism, he sees it as marvellous but not quite real. Just a shadow on the shore.