- India

- International

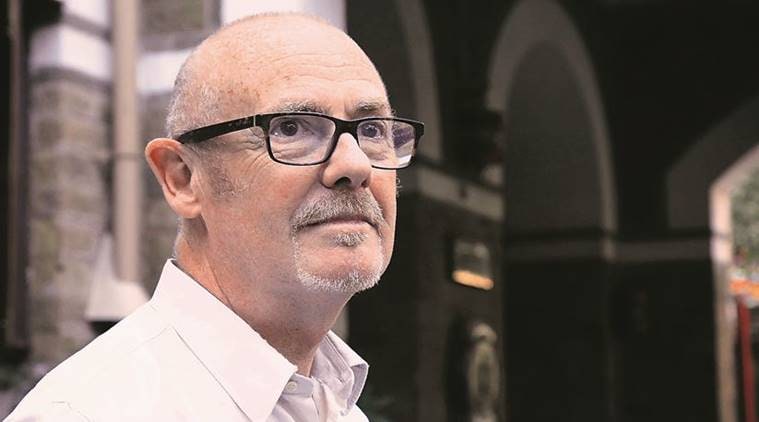

The way JMW Turner painted, with extraordinary energy, is exciting to anyone who loves painting: David Blayley Brown

In an interview to Pooja Pillai, he spoke about the British Empire as depicted in Turner’s works and why some of the artist’s most striking works were also his most controversial.

David Blayley Brown, the Manton curator of British Art at Tate Britain, is in Mumbai to deliver the 19th Vasant J Sheth Memorial Lecture at Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya on January 24. Nirmal Harindran

David Blayley Brown, the Manton curator of British Art at Tate Britain, is in Mumbai to deliver the 19th Vasant J Sheth Memorial Lecture at Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya on January 24. Nirmal Harindran

David Blayley Brown, the Manton curator of British Art at Tate Britain, is in Mumbai to deliver the 19th Vasant J Sheth Memorial Lecture. Brown will talk about the works of JMW Turner, one of the most successful, versatile and controversial painters of nineteenth century England. In an interview to Pooja Pillai, he spoke about the British Empire as depicted in Turner’s works and why some of the artist’s most striking works were also his most controversial. Excerpts:

Turner never actually came to India, so why give a lecture on his work here?

Although Turner was a great traveller, he never came this far. But he did imagine India in his work a few times. Then there’s the maritime theme; Mumbai is a city on the sea, it was built up through seaborne trade, and Turner was a marvelous painter of the sea. For my money, he was one of the greatest of all marine painters. I don’t think you have to be British to appreciate this. People everywhere can respond to the drama of his pictures. They also reflect how the world was changing, how the age of sail gave way to the age of steam. Also the way he painted, with this extraordinary energy, is exciting to anyone who loves painting.

How did Turner depict the Empire in his works?

Ships were going back and forth to India and all across the empire there was trade, and so Turner does specifically refer to the Empire several times in his work, such as when he painted the wrecks of East India Company’s ships after having heard or read accounts of them. There is one historical painting, which represents an incident that happened in 1786 on the slave ship Zong. There was an epidemic onboard, so the captain just had the slaves all dropped overboard to the sharks. Turner painted this incident in 1840 when slavery was already banned in Britain and across the British Empire. But there was an anti-slavery convention in London that year to try and get it banned everywhere, and Turner painted it to remind people why this awful practice should be stopped. There was also a painting, which depicted a ship full of female convicts that was heading to the penal colony in Australia, but had wrecked off the coast of France. The French offered to help rescue the women, but the captain said no because he was only authorised to take them to New South Wales. It’s fascinating that Turner, who was a man of his times, could see how wrong these things were and, uniquely, made pictures about them, because for most people they were like guilty secrets that they would just rather sweep under the carpet. A lot of conservative critics ripped them apart, and they were probably doing so because it was a distraction from having to examine their conscience. The painting of the female convicts wasn’t exhibited at all, because people advised that it was simply too awful and too controversial.

One of Turner’s India paintings is The Siege of Seringapatam. Could you tell us a little about how he painted it?

The Siege of Seringapatam is very interesting; it’s not a marine subject and it was painted very early in his career. It was done in water colour and Turner probably intended to have it engraved for printmaking to capitalise on what was then a recent incident. In England at the time, there was excitement about the growing Empire and the defeat of Tipu was played up as a great victory. There were plays about it, murals painted in London, which showed the action of the siege, and Turner got in on the act. Having never been to India and with no idea of what India was like, he consulted soldiers of the (East India) Company and others who had been there. He researched it as best as he could and he got the details such as the fortification, the building, the costumes on both sides, quite right. What he didn’t get right at all, because he had no idea what it looked like, was the Indian climate and the nature of the light here. He just made it seem like a sunny day in Europe.

There was an exchange between Britain and the Empire in terms of artistic styles. How is this represented in the Tate’s collection?

Unfortunately, we don’t have paintings by the so-called ‘Company School’, which were works by the Indian artists who worked for the Company and who developed a hybrid style which was quite beautiful. What we do have is paintings by people like Thomas and William Daniell, who were uncle and nephew, and who spent many years in India. A few years ago, we acquired a rather wonderful painting by Thomas Daniell of a treaty being signed between the East India Company representative and an Indian ruler (Peshwa Madhavrao II), for an alliance against Tipu Sultan. The painting was actually started in India by Scottish artist James Wales, who got fever and died, so Daniells finished it in England. What is fascinating is how the history in the painting is angled towards the Company, because it was commissioned by the representative who wanted to celebrate what he saw as a big episode in his career. It shows the treaty in the hands of the representative, who is handing it to the ruler, so it was clearly dictated by the Company and forced on the latter.

May 13: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05