The assassination of the archbishop Óscar Romero as he celebrated mass in March 1980 remains one of the most notorious political murders of the 20th century. The murder plunged El Salvador into a full-blown civil war which eventually left 80,000 dead and 8,000 disappeared.

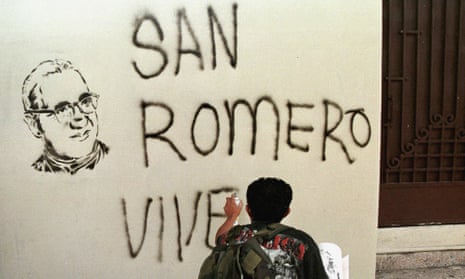

Romero is still one of Latin America’s most revered figures; his canonization – the final step to sainthood – is imminent. But almost four decades after his murder, the killers remain free.

A new book detailing the plot to murder the archbishop casts a spotlight on that impunity, unveiling previously unreported details of the conspiracy to kill Romero and offers an explanation: a refusal by El Salvador’s authorities and politicians to take on the country’s powerful elites.

“There are clear [evidential] threads on who gave the original order and who paid for the murder that any concerted investigation in El Salvador would absolutely be able to gather enough evidence to prosecute those involved,” said author Matt Eisenbrandt.

Assassination of a Saint is the first book to detail the plot to kill Romero and probe the roles played by the wealthy business owners, politicians and military death squad commanders who felt threatened by the archbishop’s outspoken criticism of the country’s military dictatorship.

Eisenbrandt was part of a team of crusading human rights lawyers from the San Francisco-based Centre for Justice and Accountability (CJA) who used an obscure American law, the Alien Torts Act, to successfully bring a civil case against one of the conspirators in Fresno, California, in 2004.

Former air force captain Álvaro Saravia went into hiding before the verdict, but later admitted to participating in the plot, and remains the only person held responsible for Romero’s murder in a court of law.

Saravia remains at large, but Eisenbrandt’s book includes interviews with other witnesses and accomplices of the crime, as well as previously unknown information from the investigation which led to the 2004 lawsuit, including details of the network of supporters who bankrolled the massacre of civilians considered communist subversives.

That included the Miami-based Salvadoran businessmen who funneled money to the death squads operated by Roberto D’Aubission – founder of the Arena party and named by the Fresno court as the “mastermind” of the Romero assassination.

One of the book’s most gripping sections is the testimony of a mole from a leftwing guerrilla group who during the 1980s worked at the Arena party headquarters. The rebel spy obtained access to a list of prominent financial donors funding death squads and also saw a “blacklist” of union leaders, teachers and others who were later killed. “Many of the top [party] leaders spoke with great pride about the activities of the death squads,” she said.

The infiltrator is one of several witnesses not named for fear of reprisals.

“Romero was allegedly murdered for $200 and life is still cheap in El Salvador; Romero’s murder remains a dangerous topic,” said Eisenbrandt.

This month marks 25 years since peace accords which brought an end to the 12-year civil war, but the deal failed to bring peace to El Salvador. A 1993 amnesty law guaranteed impunity for perpetrators, and enabled the criminal networks formed by business, military and political elites to remain intact.

Last year the supreme court declared the amnesty law unconstitutional but no one has ever been arrested for Romero’s murder – or for any other war crime. Meanwhile death squads have reportedly re-emerged in recent years, contributing to murder rates which have made El Salvador one of the world’s most dangerous countries.

Blame can no longer be laid solely at Arena’s door. The ruling FMLN – founded by former leftwing guerrillas – has shown no interest in prosecuting the case since winning power in 2009.

“We have to assume that for political reasons the FMLN also doesn’t want anyone to delve into questions that might go to the very foundations of Salvadoran society,” said Eisenbrandt.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion