Bob Budiansky, comic writer and editor

In 1983, Hasbro bought the rights to some toys from Japan, which could change from robots into vehicles. But there was no backstory to explain who they were. Hasbro had worked with Marvel to develop GI Joe as a toy, comic and animated series, so they turned to us again. Jim Shooter, my editor, came up with a six-page description of the Transformers world and asked an editor to develop names and personalities for the 26 original toys.

Jim did not much like what he got back, so he walked down a row of offices and said to all the editors working in them: “Look, we need to redevelop this, but time is running out – you’ve only got the weekend to do it.” It was just before Thanksgiving, though, and everyone said they weren’t interested. Finally he got to me. I’d only been at Marvel for six months and said: “Sure, I’ll give it a try.”

A lot of the names came from my own experiences of pop culture. Ratchet, a medical robot, was inspired by Nurse Ratched from the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Ironhide came from the old TV show Ironside. I was trying to humanise them, give them relatable qualities, such as “this guy likes jazz”. People ask how I came up with so many personalities in a weekend, but at Marvel we were creating new characters every day. That was the job.

One name I’m proud of is Megatron. Back in 1983, the threat of nuclear war felt very real – and destructive force was talked about in megatons. At first, Hasbro rejected it for sounding too scary. Gently I said to them: “Well, he’s the main bad guy. He’s supposed to be scary.” Luckily, they changed their minds.

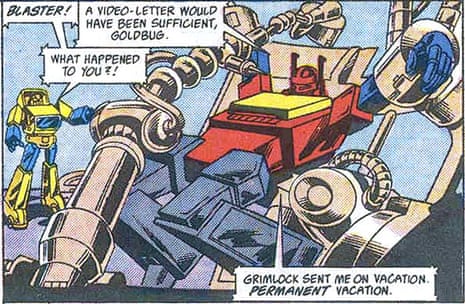

The franchise became so popular, they kept introducing new toys. It was a real challenge working out ways to bring in 15 or 20 new characters at a time. I tried to make each one unique, but after about 250, I was struggling. By the time I’d done 50 issues of the comic, I was pretty burned out.

A Hasbro executive told me that any toy that lasts two Christmases is considered a success – that was their barometer. Transformers lasted six or seven years before they started dying out. It seemed like a good run. I don’t think anybody had a clue that they would come back as a multibillion-dollar movie franchise. I certainly didn’t.

Bryce Malek, animated series story writer

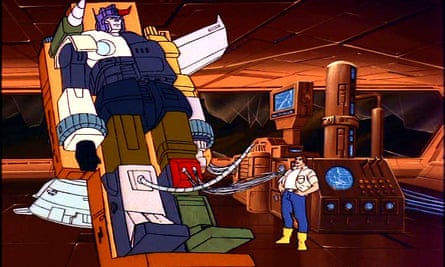

It was summer 1984 and I’d just started at Marvel, along with my writing partner Dick Robbins. We thought we were going to be doing lots of different things – but ended up just working on Transformers full-time. A three-part pilot had already been produced, but Hasbro then wanted a 13-episode series, so we had to develop a “bible” for writers, explaining how the show worked. The Transformers were stranded on Earth, but we invented a space bridge back to their home planet of Cybertron. This turned out to be useful when it came to introducing new characters.

Some writers pitched really inappropriate stuff for a kids’ show, such as the Transformers meeting space prostitutes. Oddly enough, no one ever provided us with any of the toys – we worked from photocopies of designs. I actually went out and bought a few but I never got Optimus Prime. He was too popular. You could never find one.

When those first 13 episodes were a huge hit, Hasbro said: “We want 49 more.” And we said: “Uh, OK.” Delivering the scripts on time was such a challenge: we were all just getting to grips with the computer age and our office was in the process of switching from typewriters to word processors. We had a dot matrix printer that took half an hour to print a single script – and it was state of the art.

I really wanted to emphasise the human characters in the show, to give the audience something to identify with. But in retrospect, I think the kids just really liked the robots. We were working so fast, the plots were full of holes. But I know from fan letters that kids would simply fill in any gaps with their own stories. These days I work as a clinical psychologist. I like to joke that, after screwing up so many little brains with cartoons, I’d better start fixing them.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion