- India

- International

Such a Long Journey: Migration is at the heart of Sarathy Korwar’s music

A genre-bending and genre-defying maverick, he is India’s latest export to the global jazz-electronic scene.

The Music of Migration: Sarathy Korwar drums up a dream album with Day to Day

The Music of Migration: Sarathy Korwar drums up a dream album with Day to Day

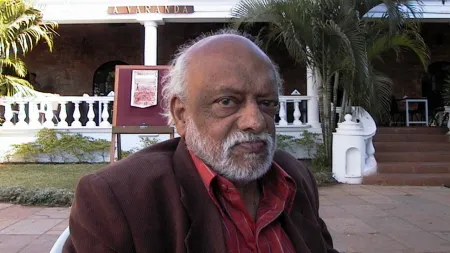

How does one begin to understand “Indian folk jazz electronica”? It’s simple — just turn to the third-last track on Sarathy Korwar’s stellar debut album, Day to Day — the whimsically-titled Indefinite Leave to Remain. It starts with counterpoint piano notes, that become percussive in their repetition, developing momentum and urgency as a funky bass and drums swoop in. An Indian vocal sample of a Siddi musician announces its arrival midway through the second minute, before the track shifts course, and with a series of dissonant chords on the piano, plunges into jazz improvisation. Then it returns to the original, bare melody. It’s a stunning composition, and feels like one is standing at a junction somewhere in a sonic universe, listening to different trains converge before taking off on their own journeys.

Korwar, 29, is modest about such analogies. “Indefinite Leave to Remain is actually a bureaucratic term that is used by migrants when they apply to stay in the UK. My girlfriend was writing that on her form while I was composing the track and I liked how it sounds. If you remove the context, the phrase sounds like something spiritual,” he says.

WATCH: Sarathy Korwar at the Magnetic Fields Festival in Alsisar, Rajasthan

Since its release last year by Ninja Tune, a UK-based independent record label who also produce Bonobo, Run the Jewels, Kate Tempest, jazz saxophonist Kamasi Washington (Korwar supported him on last year’s UK tour), Day to Day has been well-received by listeners and critics alike. Is it world music or is it jazz? Are the vocals Indian or African? The album steers clear of distinctions, and is one of the most exciting genre-bending, rather, genre-defying work to come out of India in the past few years. Korwar is a sonic wayfarer and the audacity of his ambition, and his ability to merge his varied influences on this album is nothing short of remarkable.

Korwar performs live at the launch.

Korwar performs live at the launch.

Migration — of all kinds — is at the heart of Day to Day, the seed of which lies in Korwar’s life itself. Born to parents who met at university in the US, he lived in Maryland for the first few years till the family returned to Ahmedabad. “My parents are connoisseurs of Indian classical music, it is what brought them together in the US. My father worked in software and my mother is an architect. They sing as well but I’d call it a serious hobby,” says Korwar, who, as a young boy, took up the tabla and later, the drums.

“Growing up in the ’90s, I listened to rock like most other people and played in a band. A teacher in school who was very passionate about jazz would talk to us about Miles Davis, John Coltrane with much fervour. I was only too eager to listen to music that few others were into,” he says.

What began as a mild interest in jazz would soon blossom into a deep, abiding relationship with the form. “I started playing drums more than the tabla as I grew older, even though a lot of the rhythmic ideas I have are rooted in the tabla,” says Korwar, who has trained under Rajeev Devasthali and Sanju Sahai. After his graduation in 2007, Korwar went to the UK to study drums at Tech Music School, an institute that specialises in contemporary music. “I felt out of place because the school prepares people to be sessions musicians for different genres and styles, so you know a little bit of everything and yet nothing at all,” he says. Korwar then headed to the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) for a Master’s degree in Performance and Ethnomusicology in 2011. “I was more at home there. I wanted to study the reasons and ways people make music and how it is performed and conduct experiments between genres,” he says. After the course, Korwar began working in London as a sessions musician. “But I knew I had to make my own music,” he says.

It was a chance meeting with enthnomusicologist Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy in Pune in 2014 that set him on the course to create Day to Day. “She had done a lot of work with the Siddi community in India. I watched her documentary, From Africa to India: Siddi music in the Indian Ocean Diaspora and I was fascinated by their history,” says Korwar.

The Siddis are descendants of the Bantu people, who arrived through the sea trade with East Africa as slaves, sailors and merchants, as far back as the 7th century AD, and stayed on. It is estimated that 50,000-60,000 Siddis live in villages and smaller towns in Gujarat, parts of Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Karnataka, where, stricken by poverty and isolated due to their race, the community is rendered “invisible” to outsiders. “They’re quite marginalised, even though they have lived in India for centuries. The dargah of their patron Sufi saint, Bava Gor, is here and they cannot imagine leaving it. But they have also passed down their African heritage, their culture and their music to every generation,” says Korwar, who travelled to Ratanpur, Gujarat, where an ensemble of 10-12 musicians and dancers live and work.

In Day to Day, the Siddis are heard in a plaintive chorus in Bismillah, in snatches of a conversation in Dreaming, in a devotional chant in Bhajan. “They agreed to let me record their music and their words. I informed them that what I was working on would make their music sound different,” says Korwar, who, then went into the studio in Pune with British saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings, keyboardist Al MacSween, Italian guitarist Giuliano Modarelli, bassist Dominico Angarano; Korwar played the drums, tabla, and electronics. Together, they journey into three distinct soundscapes and assemble all the strands into a heady mix.

“I know that arguments about cultural appropriation can be made, but intent, as well as consent, matter. I’m not one of the Siddis, we have different realities. What I’ve tried to do is to transpose their music into a jazz and electronic space,” says Korwar, who compensated the Siddi musicians for their performance. “At the time that I was recording the album, there was no deal with Ninja Tune. I didn’t know if I could offer them royalties from future sales,” he says.

After recording most of the album, Korwar applied to the Steve Reid Foundation in the UK (named after the renowned jazz drummer from New York who worked with Miles Davis, Fela Kuti, and other greats, and died in penury) in 2014. He was accepted and was mentored by the foundation’s patrons — Four Tet (Kieran Hebden), Floating Points (Sam Shepherd), Koreless (Lewis Roberts) and Emanative (Nick Woodmansey) and Gilles Peterson. At GOAT, an upcoming boutique music and arts festival in Goa, Korwar shares the line-up with Peterson, on the latter’s first-ever India trip.

“Performance contexts are a huge thing and I would have liked to perform live with the Siddis at Magnetic Fields last month, but it wasn’t possible. It’s a really expensive operation, so I use vocal samples when I���m performing. I actually like the disembodied voice that seems to come from nowhere and lends an ethereal quality to the show. A lot of folk music lends itself to complete surrender and that’s the goal, to reach a point during the performance where we become the music,” he says.

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05