- India

- International

Speakeasy: The Signs Are Here

A new Sanskrit book in parallel text throws open possibilities of intuitive accessibility.

Stotra Ranjani will make common Sanskrit prayers, which are still in daily use in many homes, accessible to readers.

Stotra Ranjani will make common Sanskrit prayers, which are still in daily use in many homes, accessible to readers.

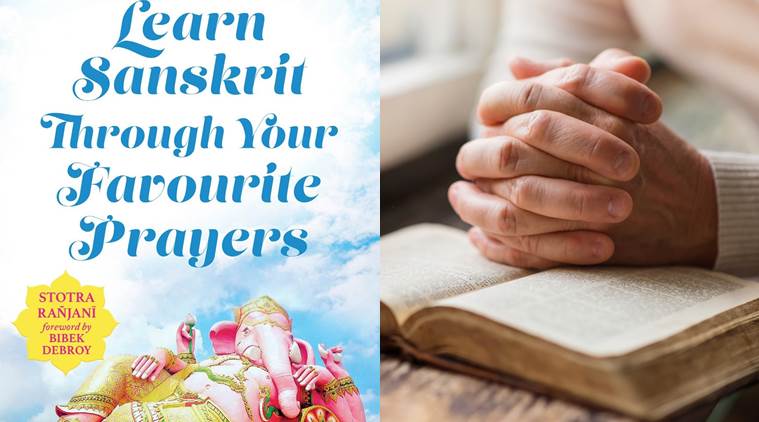

Learn Sanskrit Through Your Favourite Prayers: Stotra Ranjani

Authors: Rohini Bakshi and Narayan Namboodiri

Publisher: Juggernaut Books

Pages: 544,

Price: Rs 599

Finally, a Sanskrit book of common prayer is out in parallel text. Given the interest in Hinduism in foreign parts from the early colonial era, such a thing should have been on the stands ages ago. Stotra Ranjani will make common Sanskrit prayers, which are still in daily use in many homes, accessible to readers who have no Sanskrit, and could encourage them to learn the language formally. The imposing declension tables of classical languages, each as tall and wide as an office block, frighten off students in droves, and the future of ancient tongues may depend on the intuitive accessibility of parallel texts.

Rohini Bakshi and Narayan Namboodiri’s Stotra Ranjani strikes out beyond the traditional format, which displays the original in original script and the translation in English on facing pages, encouraging the eye to seek linguistic patterns connecting the two languages. In Stotra Ranjani, the left-hand page carries the original with a grammatical analysis in Sanskrit, plus an anvaya (concordance, or prose analysis), while the right hand page has the verse and the anvaya in Roman script. Besides, the roots of words are separated out, which is a fine way to learn the principles of sandhi naturally. And finally, there is a grammatical analysis in English.

Some of the most popular hymns of mature Hinduism are included in this book — Ganesha Pancharatnam, Vishnusatpadi Stotram and Aditya Hridayam, for instance. The deracinated devout are obvious customers. There are those who are happy to carry over Grandma’s puja room hymns, remembered from childhood, to a Mountain View drawing room. For them, just the sound suffices — perhaps, the sense rises from the collective unconscious. But there are also those who are not comfortable unless they fully comprehend the meaning of what they repeat by rote. The book will appeal to this segment.

Domestically, though, there may not be an unfelt need for this book. Homes where Sanskrit prayer and ritual persist may be as familiar with the language as they wish to be. And people impatient with the past, who believe that Bhaja Govindam is a vegetarian restaurant rather than a hymn, may find the book irrelevant to their lives. But then, there is a wave of Sanskrit rediscovery in progress, too.

The book is foreworded by Bibek Debroy, the Sanskritophile in the NITI Aayog, whose presence is a small signal of the renewed interest in Sanskrit in the government. But it is a mixed story. The government and the party behind it are largely Sanskrit-illiterate and despite vocal commitments to the language, have shown no enthusiasm to do battle with passive stems and gerundives themselves. And out there in the wild, no one really knows whether the numbers of the Sanskritagya are rising or falling. However, there is a perceivable rise in the number of forums and helplines relating to Sanskrit, to the extent that one may seriously consider learning the language without an acharya.

Rohini Bakshi started one of these resources, the hashtag #SanskritAppreciationHour on Twitter. It is one of numerous channels, from academic discussions to the Doordarshan Sanskrit News, which flourish on social media. At the same time, the web has become the storehouse of Sanskrit texts, including parallel texts. Vedanta, the Upanishads and the epics, wisdom and rattling good yarns, are well represented online since they have traditionally attracted a bigger readership. Reverse engineered concoctions like the Vaimanika Purana also draw interest, spawning spectacular stories about plastic surgery and heavier than air flight in prehistoric times, which now echo in the corridors of power. Offline, the Clay Sanskrit Library is the most famous parallel text resources, and the Murty Classical Library has picked up the baton in India.

Sanskrit has enjoyed a larger than life image among godless scientists ever since the canard got loose that it could serve as a computer language. What the myth offered was nowhere near the dream of programming computers in plain English, but the idea that machines could understand a classical language was compelling enough.

Today, Sanskrit parallel texts offer new analytical possibilities. Standardised stockpiles of texts can serve as databases for big data analysis and natural language processing. See Kyle P Johnson’s Classical Language Toolkit (http://cltk.org and https://github.com/cltk/cltk), which brings ancient languages into the ambit of natural language processing. The same strategy has already taken machine translation between modern languages beyond the level of the ridiculous, and we may soon be see translations of Adi Shankaracharya online. But then, the syllogistic minimalism of “Brahma satyam, jagan mithya”, from the Vivekachudamani (or Brahmagyanavalimala), could baffle machines by its impossible elegance. It has intrigued generations of humans. Now, the machines can have a go at it.

Parallel texts could be as old as the written word, since imperial edicts needed to communicate with multiple linguistic groups. The oldest known is the Rosetta Stone, a royal decree issued in 196 BC at Memphis in hieroglyphs, Demotic and Ancient Greek. Its discovery by Napoleon’s troops opened the door to the culture of ancient Egypt. South Asia awaits its own Rosetta Stone, without which the Indus Valley script may never be translated. Or perhaps, as machines learn more and more from the world’s literatures in parallel text, we may suddenly find a computer magically spitting out translations of the Indus inscriptions, using patterns from its vast reading in translations of the world’s literature. The key could be totally unexpected — readings of Bahasa translations of Mickey Spillane, perhaps.

More Lifestyle

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05