Dawn was breaking when the campaigners used slingshots to fire ropes on to the rig. But as they began to scale the Prirazlomnaya, aiming to unfurl a banner denouncing Russia’s attempts to drill for oil in the Arctic, their hopes of another successful Greenpeace “action” swiftly faded. They had been anticipating high-pressure hoses that sprayed freezing seawater at intruders. They weren’t prepared for balaclava-wearing soldiers shooting at their inflatable boats.

One soldier grabbed the rope used by one of the climbers, slamming her body repeatedly against the rig. They captured two other activists. Then the Russians demanded to board the Greenpeace ship. But the Arctic Sunrise’s captain, Peter Willcox, fearing his boat would be seized, resisted.

“I said, ‘Well, go ahead – open fire. But don’t hit that silver tank back near the stern because that’s gasoline and that’s going to blow us all up.’ They must’ve been thinking, ‘Who the fuck is this idiot?’ And then I was sitting in jail thinking, ‘Who was that idiot?’ But the adrenaline gets flowing.”

Willcox’s account of his 2013 jailing, alongside 27 other Greenpeace activists and two journalists, might resemble a terrifying gangster film – except that the gangsters were in government. His memoir also documents four decades of peaceful direct action against everything from whaling off Peru to incinerator ships in the North Sea, and shows how many protests eventually trigger policy change. But it’s harder to detect positive outcomes from the jailing of the “Arctic 30”. Although Greenpeace went on to successfully oppose Shell’s drilling in the Arctic, other companies have continued, and millions of barrels of oil continue to flow from the far north. As a new political era dawns, bringing the prospect of unprecedented US-Russia collaboration over the Arctic’s exploitation, Willcox is clear that the fight against climate change is only just beginning.

“I’m not sure I’ve held on to my optimism,” says the 63-year-old American, when we meet in London between his continuing missions skippering Greenpeace ships on “actions” around the world. “I’m not stopping work. I’m not giving up. I don’t want to give Planet Earth to [Trump’s nominee for US secretary of state] Rex Tillerson. But my optimism is not very high right now. Not when you’ve seen what I’ve seen.”

When Willcox was first captured by the Russians on 19 September 2013, he was optimistic, at least about his team’s prospects. He assumed they would get “yelled at for three or four days” before being dispatched over the border to Norway. But despite the ship being in international waters, armed Russian special forces had shimmied down ropes from helicopters to take over the Arctic Sunrise and tow it into custody. As if that wasn’t enough, the Russian commandos seized all the alcohol on board and had a “massive party” among themselves on their way to Murmansk.

The captain’s confidence in a quick release was also misplaced: the Russians were determined to end Greenpeace’s meddling in Arctic oil extraction once and for all, and the Arctic 30 were thrown into prison and charged with piracy, which carries a sentence of up to 15 years. The worst thing about prison, says Willcox, was that everyone – from lawyers to fellow prisoners – assumed they would be found guilty. “I saw instances where the investigator showed no qualms whatsoever about lying. I found that deeply chilling,” he says. When he was taken by prosecutors to re-examine the Arctic Sunrise, he was handcuffed to a security guard, because, he laughs, “they thought this little fat 60-year-old guy was gonna throw himself in the water, swim three-quarters of a mile to shore, and then run 80 miles through the woods to Norway. That gets kinda heavy after a while.”

Willcox had been detained by foreign forces before, but this was different: he lost 20lb in three weeks and suffered from claustrophobia. Separated from most of his crew, he worried that they blamed him for their detention.

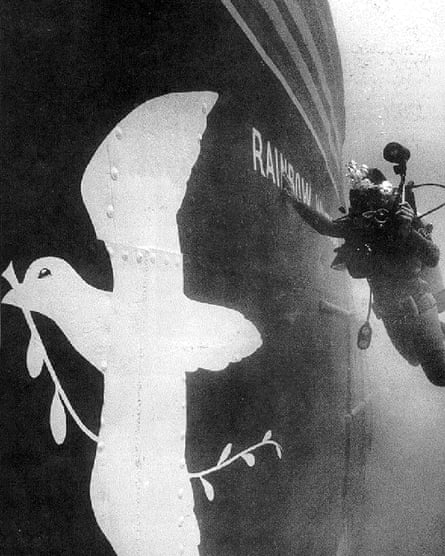

The Russian interrogation, with prosecutors “trying to make a case” against him, reminded him of the sinking of the first Greenpeace ship he skippered, the Rainbow Warrior, when New Zealand police initially suspected that the campaigners had scuttled their own boat, thus killing photographer Fernando Pereira.

In that case, detectives quickly realised Greenpeace was innocent, and two French agents, found to have planted the bombs, were arrested before they could flee New Zealand, and sentenced to 10 years for manslaughter. The agents were soon transferred into French custody, however, and released after barely two years, returning to a heroes’ welcome in France. Another French agent involved in “Opération Satanique” apologised in 2015, claiming they “did everything to preserve the life of the people on board the Rainbow Warrior”.

“That’s not true,” says Willcox. “I categorically reject that notion.” He cites the huge hole the first bomb blew in the boat, and says they could have used smaller bombs. “They were either incredibly incompetent or they didn’t give a shit. If the first bomb had gone off half an hour sooner, 20 of us would have died, because we were all having a meeting below deck. None of us would have gotten out.” Was justice done? “Justice wasn’t done. It was not even close. To this day, the French authorities have never apologised to the Pereira family or to Greenpeace, and I think that’s a mistake on their part.”

After the Rainbow Warrior was sunk, Willcox immediately joined another Greenpeace boat, so determined was he to continue to highlight French nuclear testing in the South Pacific. He was promptly detained again and banned for life from French Polynesia.

But his arrest in Russia nearly 30 years later was, he says, more frightening than the most extreme storms he has endured on the high seas. The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled that the Arctic 30 should be released, but Russia ignored the directive. Only after objections from the Pope and 12 Nobel prize winners were the campaigners abruptly freed, after two months in detention. Willcox is convinced they were only saved by the fact that the Winter Olympics were soon to be held in the Russian city of Sochi. “I don’t think they wanted us there for Sochi. They didn’t want any demonstrations or negative vibes,” he says. To Willcox’s relief, he was greeted with hugs from his crew members. “I was like: ‘Thank God.’ I wasn’t feeling guilty but I was thinking they might think I was guilty – I’m the last person in charge.”

Just as after the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior, Willcox’s detention in Russia redoubled his determination. Three months later, he helped Greenpeace block a tanker bringing Arctic oil into Rotterdam. “As far as I’m concerned we should do an action on every one of their tankers getting into Rotterdam, and hit them again and again,” says Willcox.

As for Greenpeace as a whole, however, Willcox argues that the detention of the Arctic 30 appears to have had a chilling effect. Did the brutality of the Russian reaction scare the charity away from taking further action?

“I’m not sure if that’s our official response. You might ask somebody a few levels higher up,” says Willcox. “But what am I going to tell my friends if I get arrested in Russia again? They are not going to be sympathetic. This time they’re gonna say, ‘You’re stupid.’ And what am I going to tell my kids? I don’t wanna tell my kids I’m stupid. They think that already maybe,” he laughs. He has never turned down a mission from Greenpeace’s Amsterdam HQ, but “if Greenpeace said, ‘We’re gonna do that oil rig again,’ I’d say, ‘I really respect that but I’m not going.’ Things are tough enough in Russia. If they decide to lock you away for 10 years, there’s not going to be much anyone can do about it.”

As oil continues to be imported into Europe from the Arctic and Donald Trump’s presidency looks likely to intensify US exploitation of fossil fuel, Willcox believes Greenpeace faces its toughest battle yet. There are a few reasons for this. For one thing, “our actions are getting harder because they don’t have the punch they once had,” he says. “In a world where you have 15-year-old girl suicide bombers, it’s pretty hard to compete.” Also, while he still has faith that Greenpeace’s actions “inspire” campaigners, he’s not sure Greenpeace itself has. “That’s something Greenpeace has maybe been forgetting for the past five years. When anybody does an action and returns to their desk, they have eight times more energy than they did the week before. That’s not to be trivialised. Doing silly actions may not be appreciated anymore, and the public may be getting tired of it, but I believe there’s a place for them.”

He doesn’t accept, yet, that Greenpeace has lost its radical edge: “Radical is being able to take stands that are difficult. Protesting whaling now – any hippie in the world can do that. Taking on the oil companies, that’s huge. It’s like that quote sometimes attributed to Gandhi: ‘First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.’ Now they [the oil companies] are fighting us. They are fighting us really hard, and it has been tough for us. The last five years have not been great at Greenpeace.”

He cites “a bunch of difficult things” that have happened recently, including Greenpeace having to apologise after activists accidentally damaged a Unesco World Heritage site in Peru

. “We leave some footprints and we’re the biggest enemies of Peru?” he demands. “No, we’re not. We’re the enemies of the oil companies.” Was another of the “difficult things” Greenpeace’s financial challenges, the charity having to apologise, in 2014, when

a staffer lost £3mon the foreign exchange market? “That was our mistake, which I’m told can’t happen again,” says Willcox. “There’s just a general climate of things getting harder because the fossil fuel industry can see the end in sight. Now they are angry, now we’re no longer a joke, and things are getting tougher.”

Willcox believes “there’ll be a place at Greenpeace for me as long as I want to keep going” – and he does. “I still wake up in the morning with an urge to burn the oil companies to the ground because that’s what they are doing to us.”

Greenpeace always keeps its future actions secret, but Willcox will next sail off to highlight threats to wildlife posed by the ongoing search for oil. “I like it because it’s a serious campaign; it’s the lungs of the planet and we’re smoking,” he says.

He expects Greenpeace to intensify its campaign against fossil fuels under Trump. “The fossil fuel industry is the biggest in the world. To close it down is a huge undertaking.” Willcox is worried about Trump’s position on climate change, his appointment of Tillerson and his potential co-operation with Russia over Arctic oil. “He’s appointed the head of ExxonMobil to be secretary of state. Exxon knew about global warming nearly 40 years ago, and rather than deal with it in a responsible manner, they chose to bury it. Tillerson and their ilk have been selling the futures of their grandchildren for money. I would be very happy to see the US and Russia have a less confrontational relationship, but if it’s based on the fact that both want to build up their nuclear weapons arsenals and drill for more oil in the Arctic, I don’t see much good coming out of that.”

‘Bombs? Who said anything about bombs?’: an extract from Peter Willcox’s new memoir

Whump!

A large shiver went through the entire ship and woke me from a dead sleep. I didn’t so much hear it as feel it. Disoriented and in the dark, I tried to make sense of what had just happened. As the captain of the Rainbow Warrior, I knew that whatever that whump was, it wasn’t good. My sleepy mind slowly began to run through the possibilities. The adrenaline hadn’t hit me yet.

Had we collided with another ship? Possibly. Were we at fault? I looked out the porthole in my captain’s cabin. We were tied up at the dock – Marsden Wharf, in New Zealand – so if there had been a collision, at least we weren’t responsible. Well, that’s a relief, I thought, glad that whatever had just happened wasn’t my fault. Even though I was only partly alert, at least my career survival instinct was intact.

Was the New Zealand navy firing at us? At the dock? It was the only thing I could think of, and that didn’t seem very likely. Whatever was going on, it didn’t make sense and it wasn’t over. I looked down at first mate Martini Gotje and told him to pass on the word to abandon ship. Abandon ship!? At the dock!? It seemed like a strange order to both of us, but he did not argue.

“Are there any more bombs aboard?” asked the fire chief who had just arrived. Bombs? Who said anything about bombs? Greenpeace was – and is – very much against the use of any kind of weaponry, violence, or property destruction. There was absolutely no way that we had bombs aboard. Still, we were all asked to go with the police to the station right across the road. Great, I thought. My ship has been sunk. Fernando [Pereira] is probably dead. The police think we did it, and they’re going to interrogate us. And I’m not wearing pants.