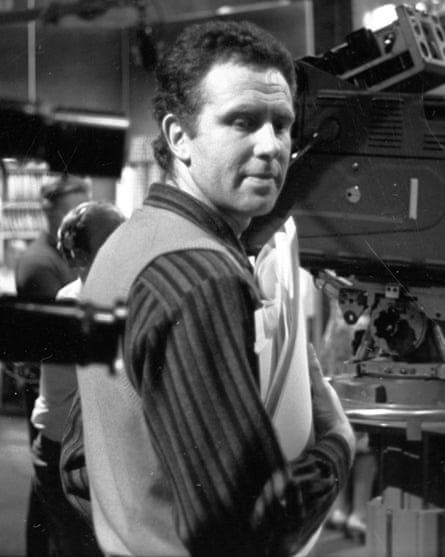

The director Philip Saville, who has died aged 86, was an important figure in British television drama – an innovative practitioner who brought Alan Bleasdale’s 1982 drama Boys from the Blackstuff to the screen. The series, which concerned the harrowing effects of unemployment on five Liverpudlian men, had a difficult gestation – the BBC was not easily persuaded to allow a supposedly “arty” director to convey the reality of the disenfranchised working classes. While he greatly admired Bleasdale’s scripts, Saville suggested rewrites, notably expanding the role of Angie, the wife of one of the men, Chrissie (Michael Angelis). This added a strong female element to an otherwise male-dominated piece and provided Julie Walters with a breakthrough role.

One episode, Yosser’s Story, featured the broken Yosser Hughes (Bernard Hill) desperately asking “gissa job” as his sanity was eroded along with his self-respect. By shooting Yosser’s Story on film, Saville gave it a haunting grandeur (the other episodes benefited from the immediacy of being made entirely on videotape, unusual for the time). The series won the Bafta award for best drama serial.

Saville was born in east London. His father, Louis – whose own father, Joseph Saffer, had anglicised the family name, appropriately adopting one related to his trade as a master tailor – was a travelling salesman for a clothing company. Philip’s mother, Sadie (nee Tanenberg, and known as Kay), was the supervisor of the women’s fashion department at Fortnum & Mason in Piccadilly.

During the second world war he attended several different schools, then began a science-based course at the University of London, and enrolled at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (Rada). He was called up for national service and posted to the Royal Corps of Signals in Catterick, but was discharged following an accident with an armoured vehicle that badly damaged his knee.

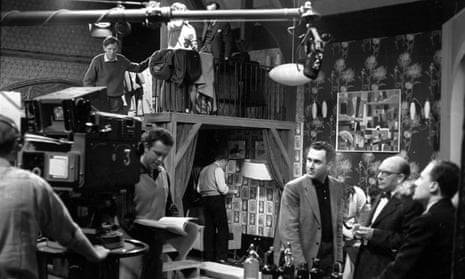

He spent some time in the US – studying Shakespeare, acting and directing – and then back in the UK in the late 1950s appeared in low-budget “quickie” films. Adept at electronics – he enjoyed fixing radios – he was then drawn to the new medium of television. Having directed the TV movie Curtains for Harry (1955), co-written by his wife Jane Arden (whom he had married in 1947) and Richard Lester, he joined ABC Television, for whom he would direct more than 40 episodes of Armchair Theatre (from 1956).

Great technical skill was required to realise his ambitious visuals – the framing and camera angles – as many of these productions were live. His trademark was inventive use of the camera, and he sometimes used mirrors to create offbeat, beguiling imagery or otherwise unachievable shots.

His intense 1960 production of Harold Pinter’s A Night Out was a breakthrough success for both writer and director, topping the week’s ratings. He also directed Pinter (and Arden) in Sartre’s In Camera (for the BBC’s Wednesday Play, 1964) and returned to its subject of existential angst in The Logic Game (1965).

He could be a hard taskmaster, but won the respect of his crews because he always had the best interests of the production at heart and the results were of the highest quality. His visual experimentation worked in harmony with a keen intellectualism, and he pushed the envelope both technically and in terms of subject matter. Indeed Three on a Gas Ring (1959), about a unrepentant single mother who elects to bring her illegitimate child up on a houseboat with two other women, was never broadcast. The Independent Television Authority watchdog felt it might “encourage immorality and destabilise family values”.

For The Madhouse on Castle Street (BBC Sunday Night Play, 1963), he flew in Bob Dylan, whom he had seen performing in New York City, to play the lead part. It soon became apparent that this would not work, so Saville split the role in two, hiring David Warner to do the acting while Dylan did the singing.

In 1964, with Hamlet at Elsinore he broke new ground by recording the play entirely on location (with a Danish crew) at Kronborg Castle. Christopher Plummer was Hamlet, Robert Shaw Claudius and Michael Caine Horatio. Saville’s technically sophisticated BBC production of EM Forster’s The Machine Stops (1966) won the top prize at the 1967 Trieste international science fiction film festival. The Play for Today Gangsters (1975, by Philip Martin) mixed gritty urban realism with offbeat storytelling and spawned a successful spin-off series.

Tall, handsome and urbane, Saville had a personal life that was as rich and vivid as his work. He and Arden separated in the mid-60s, but did not divorce. Saville’s affair with the pop artist Pauline Boty was said to have inspired the film Darling (1965). He and Diana Rigg lived together for some years from the mid-1960s. When preparing Count Dracula (1977, still regarded as one of the most faithful adaptations of Bram Stoker’s novel), he auditioned the actor Nina Francis. He did not cast her but eventually, in 1987, they married.

After Boys from the Blackstuff, he won another Bafta (beating Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective) for The Life and Loves of a She-Devil (1986). It was an effective retelling of Fay Weldon’s novel, as was The Cloning of Joanna May (1992). Later work included The Buccaneers (1995, a controversial adaptation of Edith Wharton’s unfinished novel), My Uncle Silas (two series, 2001 and 2003, with Albert Finney playing HE Bates’s character) and The Gospel of John (for the Canadian Visual Bible project, 2003). In 2009, his documentary Pinter’s Progress shed a personal light on the playwright, and latterly he taught aspiring actors at Rada.

His feature film work included Stop the World I Want to Get Off (1966), Oedipus the King (1967), The Best House in London (1969), The Fruit Machine (1988) and Metroland (1997), with Christian Bale and Emily Watson .

At the time of his death he was putting the finishing touches to an autobiography, provisionally titled They Shoot Directors, Don’t They?

He is survived by Nina and their son, Waldo; by two sons, Sebastian and Dominic, from his marriage to Arden (who died in 1982); and by a daughter, Elizabeth, from another relationship.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion