It was only when Nandita Godbole began tracing her family’s story that she realized how much she did not know about her background.

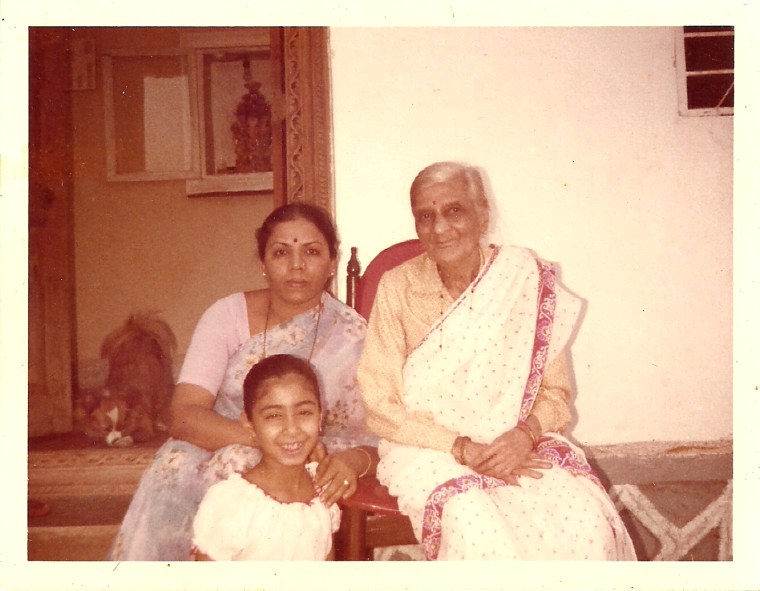

“When I was growing up in India, we would visit my dad’s parents a couple times a year... There was never really any talk about [my grandmother’s] heritage,” Godbole, a food writer who has written two cookbooks, told NBC News. “I started thinking about her because I didn’t know anything about her. When she passed away, [I] was probably around ten and you aren’t really thinking about life and death and everything at that age.”

Godbole would later discover that her grandmother was born into the Bene Israel — one of India’s oldest Jewish communities — and ended up converting to Hinduism when she married her grandfather in the 1930s.

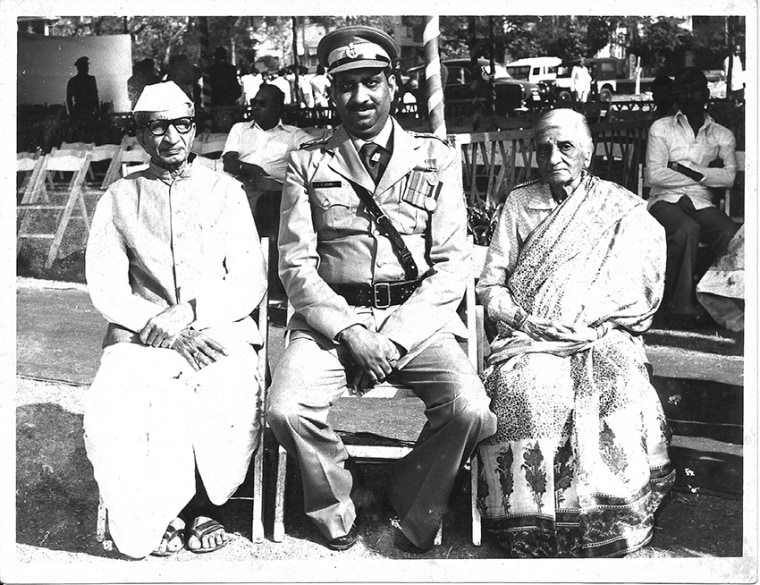

In addition to being a mixed marriage, the relationship raised eyebrows because it was what Indians call a “love match” at a time when the vast majority of relationships were arranged. “I got to the point where I said, ‘There is more to this story than I know. What do I do and how do I find out more?’” Godbole said.

The story of her grandparents is just one of the branches of Godbole’s family tree that she plans to explore in her upcoming book, “Not for You: Family Narratives of Denial and Comfort Foods,” which she is currently crowd funding. “After writing two cookbooks, I started looking into why I had this specific appreciation for who I was and where my values came from,” Godbole said.

"I started looking into why I had this specific appreciation for who I was and where my values came from."

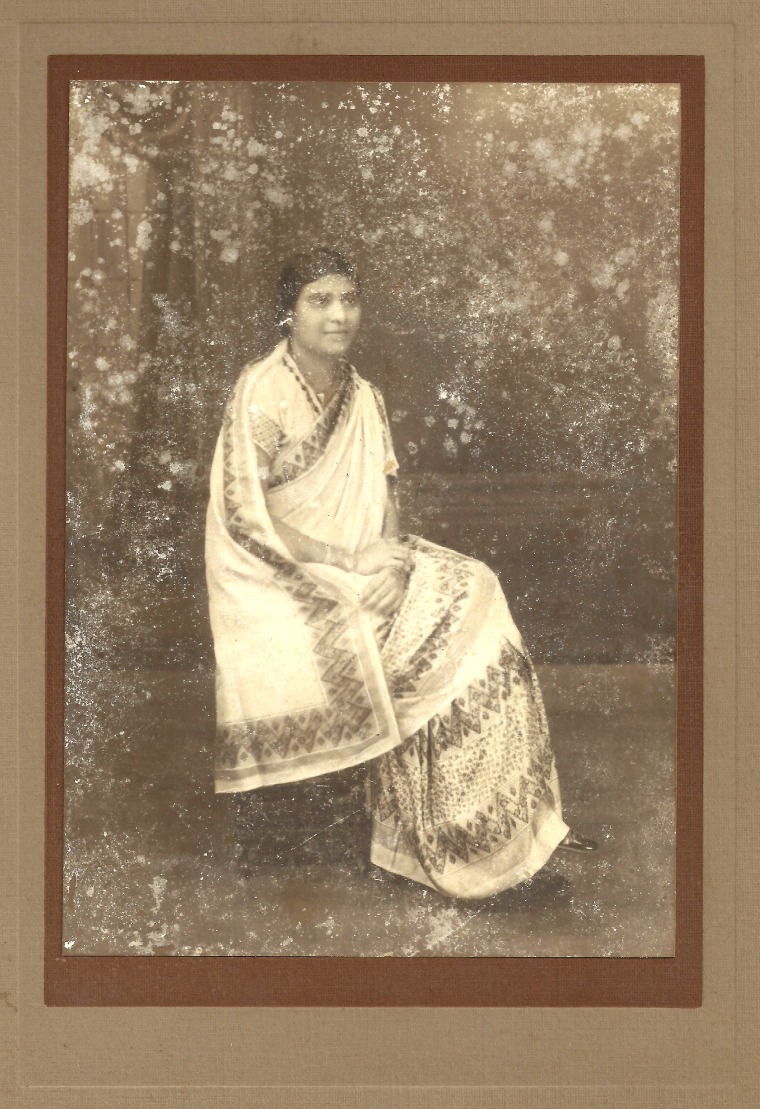

Born Esther Isac Sankar, Godbole’s grandmother met her grandfather while they were both students at the only English school in the Indian city of Alibag, which is also home to a synagogue and a small Bene Israel community, according to Godbole. “I believe he proposed to her when he had finished college and started teaching,” she said. “My grandmother was living in a hostel at the time and he said, ‘I would like to marry you.’ It was a very idealistic time and they were caught up in it.”

Esther Isac Sankar would change her name to Pramila Godbole after her marriage and officially convert to Hinduism. “Mixed marriages weren’t as accepted then,” Nandita Godbole said. “It was more like ‘you are a Hindu’ now and there wasn’t any discussion about it. For all practical purposes, she hadn’t kept a Jewish household at all.”

It was not until Godbole began interviewing her father about his life a few years ago that the family realized that there was one significant place the former Esther Sankar had been keeping tradition alive — in the food she cooked each day. While her grandfather was a Brahmin and didn't eat meat, Godbole's grandmother still cooked with chicken, goat, and fish, she said.

“She brought the idea that she wanted to cook chicken, goat, and fish in her home," Godbole said. "We were talking about this with my dad and my mom once and we thought maybe there were parts of her that she couldn’t let go of. When I was writing this book and started documenting it all started becoming more and more apparent there were traces of her heritage everywhere.”

Godbole was struck by the role food played in both the lives of her grandmother, her father, and herself. The conversations she had with her father took place when he was in his 70s. It was an emotional experience for them both.

“When I asked him, ‘Dad, do you remember anything when you were growing up of what ajji (my grandmother) cooked?’ and he said the one thing that he remembered was that she made sandan [a mixture of roasted semolina and coconut milk that is steamed or fermented and can take days to prepare] for a certain festival,” Godbole said . “He was 75 when he passed away and he had Parkinson’s and his memory was going, but he said he remembered sandan. And it took him a good part of that day — that was his task for the day — to remember what he liked about it. We would go back and talk to him and ask, ‘Did she put this in it? Did she do it this way?’ And then experimented with it and we made him some sandan.”

One of the challenges Godbole had in researching for "Not for You" was identifying which foods and recipes were specifically from the Bene Israel side of the family. There was often significant overlap between the many cuisines of the region, Godbole said. She also realized how she herself incorporates Jewish culinary customs into her life.

“The most important part of that influence is in my kitchen,” she said. “I will think 12 times before I put fish and milk together [because it’s not kosher]. Whenever I’ve learned any type of cooking from my mom, it’s always been, no you never mix these two things together and, if we had fish for lunch, for example, then nobody is going to have tea or coffee with milk a few hours afterwards.”

Each chapter of Godbole’s upcoming book will end with a recipe from one of the branches of her family. Here, she shares her grandmother’s recipe for pineapple malpua, which was often served on holidays.

Ananas or Pineapple Malpua (Fritters)

From "Not For You: Family Narratives of Denial & Comfort Foods," by Nandita Godbole

"These decadent pineapple fritters are most often prepared as a Hanukkah treat amongst members of the Bene Israel community, who live in and around Mumbai, India," Godbole said. "This recipe is more often made with bananas or apple rounds as those fruits are readily available, but pineapple malpua makes for an extra special addition to festive dessert platters."

Ingredients

For Malpua

- 1/2 cup milk

- 1 egg

- 2 cardamom pods, crushed fine

- 1/4 cup sugar

- 2/3 cup all-purpose flour

- 1/3 cup fine semolina

- 2 tablespoons freshly grated coconut, optional

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon vanilla, optional

- 8 to 10 thick-cut pineapple slices

- Cooking oil for deep frying

For Whipped Cream

- 1/2 cup heavy whipping cream

- 2 to 3 tablespoons sugar

- 8 to 10 saffron strands

- 1 to 2 tablespoons sugar, optional

Method

Whisk the heavy whipping cream with sugar and saffron to stiff peaks. Cover and set aside in the refrigerator until ready to use.

If using canned pineapple, drain the slices, set them on a paper towel or in a colander to drain for 15 to 20 minutes before use. If using fresh pineapple, pat them dry and set aside until ready to use.

Whisk the milk, egg, cardamom powder, and sugar together in a shallow bowl until the sugar has completely dissolved. Stir in the all-purpose flour, semolina, salt, fresh coconut, and vanilla (if using) to make a thick smooth batter, ensuring there are no lumps. Cover and set aside for 45 minutes. Check to see if all the semolina is moist and softened before using it to make the fritters.

Heat cooking oil in a suitable frying pan (oil must be at least three inches deep to allow the fritters to fry well). Test the oil with a drop of batter — if the batter rises to the top immediately, the oil is hot enough. Reduce the heat to medium low.

Carefully dip single pineapple slices into the batter and turn each slice once to coat fully; do not turn over more than once as the slice can break. Hold each batter covered slice over the batter pan to let extra batter drip away. Carefully lower the pineapple slice, one at a time, into the hot oil. Do not crowd the oil with too many pineapple slices, as they cook quickly and need the room when you turn them over. Fry until each side is lightly golden brown, about one minute on each side. If the batter is browning quickly, reduce the heat to low. Once each side is cooked, carefully remove each fritter using a spider or strainer and set aside to drain on a paper towel for two to three minutes to cool. Do the same with all remaining pineapple slices.

Serve the pineapple malpuas at room temperature with a side of the saffron whipped cream. Dust with granulated sugar for extra sparkle.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr.