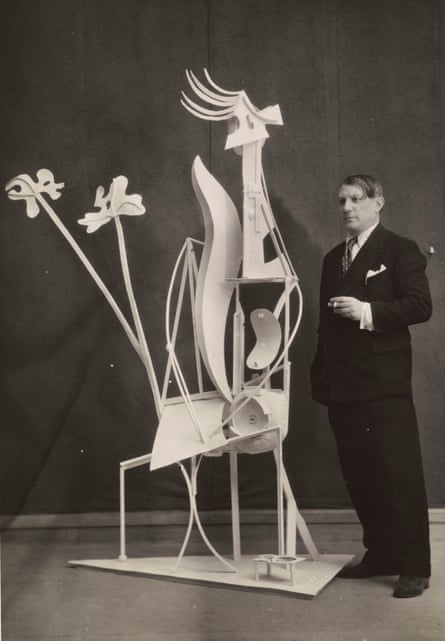

1.Picasso Sculptures

Museum of Modern Art, New York

This was the best exhibition of the 20th century’s greatest artist that I have ever seen. I am so glad to have caught the last few days of the French version of a show originally staged by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, for it was a sensual thrill, an imaginative helter-skelter, an intellectual blast.

Picasso is the most serious and flippant of artists. You couldn’t escape the flippancy here. From carving primitive figures of his girlfriend out of sticks and bits of wood on their summer holiday in 1906, to making a baboon with a toy car for its head in 1951, he always seemed to treat sculpture as child’s play. That was probably because he thought of painting and drawing as his “true” arts, and three-dimensional stuff as a bit of light relief. The freedom this completely unpompous attitude unleashed is delirious. Picasso takes a glove, sticks it to a relief and covers it in sand. He makes a Cubist absinthe glass, does a bit of welding, whips up a ceramic faun – whatever he feels like, really.

At no point in this exhibition does Picasso look like a professional sculptor. What he does look like is the greatest sculptor of the 20th century. His readymades are far more poetic than Marcel Duchamp’s, his abstractions more exciting than the much narrower art of Giacometti or Brancusi.

The boundless creativity of Picasso’s sculpture is staggering. One of the most dazzling rooms in this exhibition brought together gigantic busts of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter that he made at the start of the 1930s. Beginning with a fairly realistic portrait, the display revealed him increasing the size of her nose until it swallows up her face. Following this metamorphosis in sculpture after sculpture was like being inside Picasso’s explosive mind, sensing something of the magical way he experienced the world.

Why was this my exhibition of the year? Because it did justice to Picasso’s genius. It was energetic and copious enough to keep up with him. The array of Marie-Thérèse Walter was just one of a series of coups de théâtre in which sheer generosity of loans and assiduousness of curating delivered visual treats. This exhibition did not settle for half measures. It had to have all the visceral, flayed heads of Fernande Olivier that he created in 1909, all the absinthe glasses he made at the climax of his cubist period five years later, and the startling wood carvings he made when he was imagining Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1906. The constant revolutionary impulse of Picasso has, I suspect, never been more brilliantly revealed. That’s why he emerged so authoritatively here as the modern world’s true god of sculpture, and an artist for our time with no respect for what art “should” be.

After seeing this I couldn’t take the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Picasso Portraits seriously. It was parsimonious by comparison and just did not capture the energy that flowed so fast and strong at the Musée Picasso. Britain often accepts as “blockbusters” shows that are actually quite skimpy. Picasso Sculptures delivered.

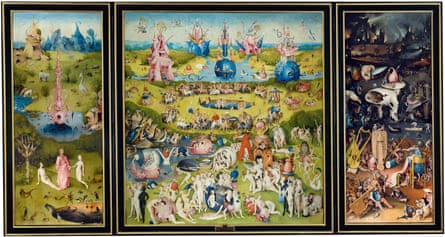

2. Hieronymus Bosch

Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch, Netherlands

The most mind-boggling marvel in this unprecedented, probably unrepeatable retrospective of one of the most imaginative artists of all time, at the local museum in his home town, was not a psychedelic altarpiece but a display of drawings. I had never seen a drawing by this medieval genius before, but the research project that made this exhibition possible has identified a surprisingly large corpus of sensitive sketches by him. To look at Bosch’s drawings, his most intimate, personal works, was to see the world through his paranoid, unhappy eyes. The paintings in which he enlarges on his private fantasies of monstrosity and mayhem were lent by museums all over the world – a fantastic array in every sense. On the day I visited, it was carnival time. People were eating chips in the rain. In the art of Bosch the nightmare carnival never ends. Read a review

3. Beyond Caravaggio

National Gallery, London

I have a confession. I would rather visit an old museum or stately home and explore its shadowy paintings than queue for most hot-ticket exhibitions. That is why I absolutely love this one, because it manages to recreate the fun of exploring old master collections for yourself, in an exhibition. The curators have uncovered a rich haul of half-forgotten works by Caravaggio’s imitators, from the bizarre to the brilliant, with Artemisia Gentileschi arguably the biggest find of all. Then there’s the man himself. There are only a few paintings by Caravaggio here, but they include his sublime visions of the Taking of Christ and St John, and cut into your brain with daggers of light and threats of shadow. Read a review

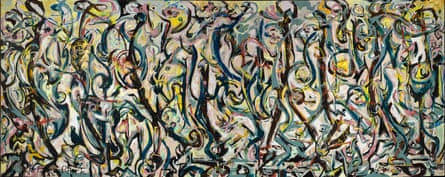

4. Abstract Expressionism

Royal Academy, London

The power and the glory of America’s greatest painters fits well into the palatial spaces of Burlington House. This exhibition made use of every inch of those grand walls to offer an encyclopedic history of one of the most ambitious, courageous, liberating adventures in the story of modern art. It made me see these artists in a new way, and while the revolutionary art of Jackson Pollock is powerfully celebrated (seeing his first really great painting, Mural, opposite his last, Blue Poles, is quite a moment), it also reveals the true brilliance of artists like Franz Kline and Ad Reinhardt. Yet the most sublime artist here, from his troubled early self-portrait wearing blue glasses to his majestic poems of uneasy colour, is Mark Rothko. Read a review

5. In the Age of Giorgione

Royal Academy, London

This was a sensitive and subtle exhibition about a sensitive and subtle – and incredibly rare – artist. Giorgione was more famous than his friend Titian until, in modern times, a more scientific attitude to art history reduced his once abundant body of work to barely anything at all. Some of his undisputed masterpieces, including his brilliant, challenging painting The Old Woman, were shown here among works that may or may not be by him, and those of his contemporaries. The result was a truly beautiful evocation of the spirit of experiment that flourished in Venetian painting at the start of the 1500s. It may not be any easier to identify true paintings by Giorgione, but this important event put the “Giorgionesque” mood of delicate sensuality right back at the centre of western art, where it belongs. Read a review

6. Anselm Kiefer

White Cube Bermondsey, London

Staggering stuff from the greatest living artist – I think he’s clinched that title now – with an exhibition of new work that somehow manages to be even more impressive than his retrospective at the Royal Academy in 2014. The theme is the death of the gods, and Kiefer makes of this Wagnerian stuff a mythology for our time – with eerie echoes of another time, 1945, the year of Hitler’s Götterdämmerung and the artist’s birth. Turning the gallery into a haunted bunker or U-boat, laden with the beds of dying heroes, Kiefer makes history new and horrible. Then you discover his stupendous paintings that defy the difference between two and three dimensions. This is 21st-century art at its most pungent, shocking and valuable. Read a review

7. William Kentridge

Whitechapel Gallery, London

History is a chaos of ever-changing images for Kentridge. Defining moments of the modern era haunt this compelling exhibition of film and video enflamed by his flickering sketches, and staged in playfully sculptural setups. Einstein’s theory of relativity, the Russian revolution, the birth of dada at the Cabaret Voltaire and Méliès’ early film masterpiece A Voyage to the Moon are among the ghosts of modern times that haunt this comic and serious art. Kentridge himself is history’s witness and helpless, hapless clown, appearing in these films as an ageing melancholic artist who could easily be the central character in a Paolo Sorrentino movie. His art is as suggestive and ambitious as an epic novel by a 21st-century Thomas Mann. Read a review

8. South Africa: Art of a Nation

British Museum, London

William Kentridge is one of the modern South Africans whose art is seen against a staggering historical and prehistorical epic landscape in this survey of three million years of art. Really. The oldest work here, a “found portrait”, was picked up by an early human ancestor that long ago. Actually, it’s a pebble shaped like a face. Call that art? Well, art here means not just creativity, but things that help people to live and struggle. Spears and anti-apartheid badges tell as much about the anguished history of South Africa as masks and paintings do. And yet, it includes a San rock painting that is among the greatest artistic masterpieces you will ever see. Read a review

9. Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings

Courtauld Gallery, London

I’d never heard of this Victorian medium before the Courtauld Gallery put on a dazzling display of her paintings. Houghton believed the spirits of dead artists, including Titian, guided her hand to create her swirling spirit drawings. If so they must have seen into the future, for her mesmerising vortices of pure colour anticipate 20th-century abstract art. The definitive abstract artists Kandinsky and Mondrian would both see their art as spiritual. Houghton takes that idea even more literally than they did. These are ghost paintings, if you like – or in modern eyes, the brilliant works of a woman whose creativity was liberated by her identity as a medium. How many more Victorian women artists are waiting to be discovered in the archives of spiritualists and old botany journals? Read a review

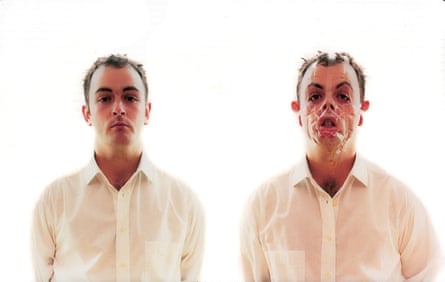

10. The Scottish Endarkenment

Various venues, Edinburgh

I loved this gothic romp through modern Scottish art that managed to put today’s feted artists, including Douglas Gordon and Christine Borland, alongside sculpture and painting going right back to 1945, on the provocative basis that they all share a taste for the dark stuff. The city of Burke and Hare and Robert Louis Stevenson is full of evidence of Scotland’s cultural obsession with evil and madness. Here, close to the atmospheric depths of Edinburgh’s Old Town, Gordon turned himself into a monster with Sellotape, Borland spookily filmed a robot baby, and the late great Ian Hamilton Finley mused disconcertingly on the god Pan’s connection with Panzer tanks. Unreasonably good fun. Read a review

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion