The Long Legacy Of Nanjing Massacre On Asian Politics – OpEd

By Mitchell Blatt*

Today, as with every December 13 for the past four years, Chinese officials gathered at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall and rang the bell for the up to 300,000 killed by Japanese imperial soldiers who invaded and captured Nanjing in 1937.

The conquest of the Republic of China’s capital six months after the Second Sino-Japanese War started inspired joy and complacency in Japan. Just weeks earlier the Japanese had completed their capture of Shanghai, a three month battle. Nanjing fell in less than two weeks. General Iwane Matsui was confident that taking Nanjing would result in China’s surrender. (It didn’t, and the war went on for seven more years before Japan surrendered.)

Upon victory on December 13, soldiers committed random acts of violence throughout the city. Civilians fleeing were shot in the back. Homes were invaded, women raped and then stabbed. Pregnant woman were bayoneted in the stomach. Dead bodies were thrown in rivers. Much of the city was destroyed by looting and arson.

Japanese soldiers rounded up masses of men on the grounds they were suspected of being soldiers. Some soldiers had indeed thrown off their uniforms and tried to blend in with civilians, but many more of those taken out to be executed had never fought in the first place. Hundreds of POWs were tied up and shot to death by the Yangtze River on December 18.

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East ruled that Japanese were guilty of murdering over 200,000 and raping 20,000, including with foreign objects like bottles and bayonets. The government of China holds that 300,000 were killed. Mainstream scholars in the United States and Japan have made estimates of anywhere between 50,000 and 300,000.

By any measure, it was a horrendous brutality. But the historical question has been politicized by the PRC government’s insistence that any estimate less than 300,000 is tantamount to denial, and by Japanese revisionists, who produce implausibly low numbers.

Besides the fact that records are spotty, the number really depends on what scope for the timeframe, area, and definition of civilian is used. Some scholars include those killed in the suburbs surrounding Nanjing and the road to Nanjing from Shanghai, where soldiers competed to kill 100. Some include soldiers killed on the battlefield; others don’t.

Japan’s brutal World War II past has always remained a stumbling block for its relations with China and Korea. Those two countries view Japan’s sometimes mealy-mouthed apologies and its leaders’ visits to the Yasukuni Shrine as denials of history and failures to admit responsibility.

For China’s government, keeping the issue alive also serves a political purpose. History is a cudgel to swing against Japan when it tries to expand the use of its military “self-defense forces”, as it did 2015 to allow for supporting allies overseas, or when it tries to get a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Riling nationalist anger has proven a successful survival strategy for governments the world over.

Since 2012, relations between China and Japan have plunged to lows because of territorial disputes. The dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, heated up in the spring when Japan considered formally purchasing the islands, which had been owned by a private owner. On August 15, Hong Kongese activists waving Chinese and Taiwanese (ROC) flags landed on the islands. They were detained for two days and released.

Following the island landing and detention, anti-Japanese protests broke out throughout China in August and September. Besides just parading with Chinese flags and portraits of Mao, the protests also featured acts of violence against Japanese people and cars. Even some Chinese writers in government-owned outlets criticized the mob mentality.

That December also happened to be the 75th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre, a date China commemorated with sirens. In 2014, for the first time, China made the anniversary of the massacre and that of Japan’s surrender national holidays.

I remember the frenzied feeling of the time well. It was my first year working in China. I was on vacation in Dali, Yunnan during National Day, October 1, just after the protests had ceased (under the compulsion of the government, which must have felt the protests had gone on long enough and served their purpose). In the parking lot, I noticed a car with a Chinese flag on the back. Looking closer I saw the flag was covering a Toyota logo. Don’t attack my car, I’m a patriot! you could almost hear it saying. Some automobile owners said so explicitly with bumper stickers that read, “My car is Japanese, but my heart is Chinese.”

(See also: 4 Photos that Illustrate Anti-Japanese Sentiment in China)

Chinese people pigeonholed me into conversations about politics and foreign policy, asking why “my America” supported Japan. Back in Shanghai for Halloween, I competed in a costume contest. The guy next to me took the microphone and said, “His America is allied with Japan!”

As I wrote for The Federalist:

I knew just what to say. “The Diaoyu Islands are Chinese [territory]!”

The party-goers roared with applause, and I easily won the contest. … In truth, I don’t know which country has the rightful claim to the islands. I do know that Japan first took control of the islands in 1895, the same year it colonized Taiwan, beginning their era of imperialism that America eventually ended in World War II. So from that perspective their historical claim may appear problematic. However, there are other factors in territorial disputes, so the answer is far from clear.

Relations between the two countries and their people were bad before the Senkaku/Diaoyu controversy, but they deteriorated after. The leaders of the countries didn’t meet for two years, and their handshake at the 2014 APEC summit was heavily scrutinized for its awkwardness.

Relations between the two countries and their people were bad before the Senkaku/Diaoyu controversy, but they deteriorated after. The leaders of the countries didn’t meet for two years, and their handshake at the 2014 APEC summit was heavily scrutinized for its awkwardness.

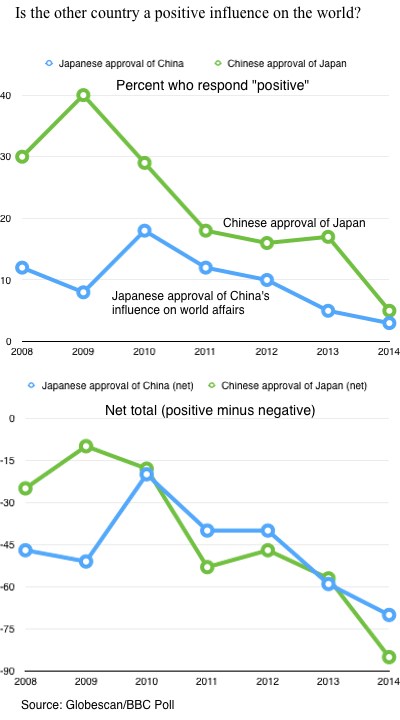

Chinese approval of Japan’s impact on the world dropped from 16 percent in 2012 to 5 percent in 2014. Japan’s view that China made a “positive impact” on the world feel from 10 percent to 3 percent. (BBC Globescan survey; 2012, 2014)

The first time China held a major victory parade to commemorate the allied victory in World War II, 2015’s 70th anniversary, I also had an illuminating discussion with a Chinese citizen about World War II history. A passage I have been working on describing the encounter:

I was sitting in a Lanzhou noodles restaurant in Nanjing when a college-aged boy started shouting at me from across the room a few tables away. It started out as an ordinary conversation, him, speaking English, asking my country of origin and such. But then, out of the blue, he asked if I knew about the Nanjing Massacre.

…

A few weeks before I sat down in the noodle restaurant, China had hosted a military parade to commemorate the 70th anniversary of Japan’s surrender on September 2. 12,000 Chinese soldiers, along with 1,000 more foreign troops from 17 countries, marched through Beijing, past Tiananmen Square, as modern weaponry followed. It was the first time China held a parade to commemorate victory in the war.Critics thought it was meant to send signals to Japan and other countries that China was to be feared. The message was: don’t get too cozy with the United States. Don’t think you can beat us in war. If we have to, we can take the Diaoyu Islands and other disputed islands with force.

High-ranking leaders of countries with oppositional interests to China in the South China Seas, like the U.S., the Philippines, and India, along with European countries, were notably absent, though Vietnam’s President Trương Tấn Sang did attend.

However, the festivities also served as a domestic message to China’s own citizens to rally them to be patriotic and support the Communist Party. Both internal and external messages are linked, however, because a nationalistic Chinese people are likely to be more riled up and supportive of aggressive measures in response to perceived slights.

The boy, whose name is Wenqing, said Chinese people are very nice to foreigners. I asked him if he would drive a Japanese car.

“No!” he said. It wasn’t even a question.

“You shouldn’t hate Japanese people. Japanese people don’t represent their government,” I said.

“In World War II, Japanese people killed a lot of Chinese people.”

By then Wenqing had come closer to me, and his mother, a Muslim Hui woman in a headscarf had pulled out Wenqing’s iPhone to film our conversation. Chinese love interactions with foreigners.

“Why, when I went to Vietnam, were Vietnamese people nice to me?”

“That is already a part of history.”

“America fought [North] Vietnam 42 years ago. Japan fought China 70 years ago. If the Vietnam War is history, why isn’t World War II history?”

“U.S. fighting with Vietnam wasn’t as serious as the Nanjing Massacre.”

Comparing one tragedy to another is pointless, but if you look at either the Vietnam War or World War II as singular events, they were both very bad. Between 1955 to 1975, America dropped and more than 260 million cluster bombs on Laos, and 2.8 million tons on Cambodia. Between 50,000 and 65,000 Vietnamese civilians were killed by U.S. bombing campaigns. Even after the war ended, many more were born with disfigurations from the use of Agent Orange, and some died from left-over bombs and land mines.

After a little break, I picked up the thread again from another angle. “You [Chinese] are friendly to Americans, right? You are friendly to British?” I stated.

That was a reference to the Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60, when Britain first waged war with China after China tried to shut down Britain’s illegal trade of opium. Britain ended up taking Hong Kong from China along with concessions in treaty ports in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo, and Fuzhou. The U.S. and other foreign powers later signed similar “unequal treaties” and took concessions. Those countries, known as the Eight-Nation Alliance, also put down the anti-foreigner Boxer Rebellion and destroyed the old Summer Palace in the process.

The “Century of Humiliation” China suffered at the hands of foreign imperialists is so driven into each Chinese person’s head by history and repetition from the government and schools that Wenqing knew what my question implied without me saying it.

“This is history,” he said again.

“When will Japan’s war with China become history?”

“It will happen slowly. Everyone should be peaceful.”

“Japan hasn’t come to terms with and admitted their World War II history. Do you think China’s government should admit its history?” I ventured.

“China is a peaceful country. Our war with Vietnam”—perhaps the Third Indochina War, a series of conflicts after the Vietnam War, or the 1974 Battle of the Parcel Islands, in which China took control of the Parcel Islands—“is also history.”

“No, no, that’s not what I’m referring to,” I said, although I had to admit he made a good argument for why China’s “peaceful development” is not what it seems. “I mean, should the Chinese government admit their history towards their own people? … For example, should they admit and take responsibility for ’66 and ’89?”

About the author:

*Mitchell Blatt moved to China in 2012, and since then he has traveled and written about politics and culture throughout Asia. A writer and journalist, based in China, he is the lead author of Panda Guides Hong Kong guidebook and a contributor to outlets including The Federalist, China.org.cn, The Daily Caller, and Vagabond Journey. Fluent in Chinese, he has lived and traveled in Asia for three years, blogging about his travels at ChinaTravelWriter.com. You can follow him on Twitter at @MitchBlatt.