I return to it

again: avid faces,

conscious of the threads

fate has spun; fingers

with scissors to cut

those threads and release

the garment towards which

the muscular lover

helplessly is being drawn.

RS Thomas was always keen on the ekphrastic genre (literature about other artforms). His wife Mildred “Elsi” Eldridge, was herself a gifted artist, and he responded to a wide variety of paintings. Many, he admitted, took the form of reproductions – sometimes even postcards, with which the Thomases would play an art-history version of Happy Families. But they stimulated his imagination in periods of what he termed “poetic driness” and gave him new angles on the metaphysical questions that absorbed him.

A collection of ekphrastic poems, Ingrowing Thoughts, appeared in 1985. But this particular vein turned out to be far from exhausted. All the poems in Too Brave to Dream: Encounters with Modern Art are recent discoveries. Some 16 years after the poet’s death, when the RS Thomas Centre at Bangor University acquired his personal library, untitled works in Thomas’s hand were found between the pages of two books, Herbert Read’s Art Now (1933) and the essay collection Reed edited, Surrealism (1936). The poems were composed between 1987 and 1993.

I should declare an interest before going on: I’m employed by Bangor University. I was never to meet Thomas, as I’d hoped; the news of his death was announced the day I started. With the edgy narcissism of the stranger in town, I began to wonder if Thomas had turned his back on me personally by dying. Well, it was raining heavily, and there’s nothing like the rain of north Wales to darken one’s mood irrationally. But then the rain mostly stopped, the sun mostly came out and a rainbow appeared over the university tower. My mood soared: I imagined I’d got a reluctant thumbs-up from the great Welsh poet in the sky.

I’m glad to be revisiting his work with this week’s poem. It’s not often that some three dozen new poems by a major poet are discovered. And this is the first time, I think, that a Poem of the week has been especially written for the accompanying picture.

Introduced and annotated in scrupulous detail by Tony Brown and Jason Walford Davies, Too Brave to Dream includes paintings by George Grosz, Graham Sutherland, René Magritte, Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso and Grace W Pailthorpe. Thomas writes about war and mechanised violence: for example, the people “too brave to dream” are Londoners whom Thomas imagines caught in the Blitz raging beyond the subway refuge Henry Moore depicted in his 1941 Shelter Drawings. Other poems contain broader observations of “the human condition”. All complement the pictures in a vivid, taut-nerved, almost intuitive way, closer to improvisations or quick sketches than to complex parallel compositions. Like little springboards, they impel the reader back to the painting, to see it with a second pair of eyes.

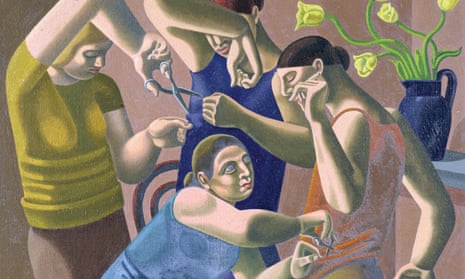

This week’s poem responds to a striking work by an artist of Isaac Rosenberg’s generation, William Roberts. What Thomas instantly sees in The Dressmakers is thread-spinning fate. So the absorbed and slightly sinister seamstresses come to resemble the three Moirai of Greek mythology: Clotho, who spins the thread of an individual’s life, Lachesis, who draws lots to determine its length, and Atropos, who delivers death by cutting the thread. The painting doesn’t precisely fit such a scenario. Yet Thomas captures the mood of it with his idea of fate and emphasises its two most significant oppositions: the fierce, greedy cunning of the thickset figure in blue and the sensuous trance-like acceptance of the woman she attends.

Thomas goes beyond Roberts with an arresting, perhaps surrealism-influenced image: he imagines the threads, when cut, “release / the garment”. Is the garment that stripy, flimsy shift the woman on the right is already wearing? The item of clothing Thomas imagines is more likely to be metaphorical, and even identifiable as Death.

While “the muscular lover” could be outside the picture’s frame, I take Thomas’s term to refer to the shift-wearing woman. The painting suggests perhaps that she’s also being prepared for some bridal ceremony, the nail scissors wielded by the leading dressmaker symbolising the breaking of the hymen. We can’t see her face but, as the poem implies, there is no protest. She is “helplessly being drawn” (the pun on the passive verb intensifies the helplessness) towards her fate, Eros – which is also Thanatos.

It’s always difficult to know whether, in a single-stanza poem, a syllabic pattern is intended. Thomas begins with a five-syllable line, and there are five more lines of five syllables at the core, if you pronounce “towards” in line seven as a monosyllable. No line has more than seven syllables. This emphasis on five seems to mirror the extraordinarily expressive fingers and hands Roberts has painted.

Faces, threads, fingers, scissors and the garment itself are central images, almost functioning as archetypes. With less connective narrative than Roberts brings to his ensemble, these images enact in the poem an exposed, bare ritual. At the same time, the syntax has a consenting, graceful flow. Thomas’s speaker doesn’t condemn what’s happening, though it’s clear from his lingering closing line that he sympathises with the lover. His “garment” may be an allusion to the frailer dress of mortal flesh. The artist evokes a certain dramatic menace, despite those cheery tulips – but the poet seems quietly unalarmed: fate, for him, simply does what it has to do.

Thomas regretted that the images accompanying his earlier ekphrastic poems were monochrome. How delighted he’d have been with this gloriously full-coloured edition, a gift for anyone, not least at Christmas time, with an interest in poetry and art.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion