It was meant to be a paean to Sir Neville Marriner, the British conductor who for a while directed the Athens Concert Hall’s resident orchestra, the Camerata. But, standing on the podium, an audience in frocks and suits before him, Nikos Tsouchlos, the hall’s former artistic director, found it hard to hold back.

With the comportment of an undertaker he cleared his throat. “If Marriner were alive today it would be very hard to persuasively explain to him why this same orchestra has spent the past 20 months without an administrative board,” he said, listing the indignities that have befallen the ensemble in recent years. Even its musicians, he said, had “been brought to the edge of living decently”.

The outburst – moments before a performance by the Academy of St Martin in the Fields this week – highlighted the depths to which culture has been hit in a country grappling with its worst financial crisis in modern times.

The Athens Concert Hall, or Megaron Mousikis, was Greece’s premier cultural institution before the crisis struck. When, in 1991, after a long wait, the Megaron finally went up – its interior decked out with monumental chandeliers, Dionysos marble, American oak and acoustics to rival any in Europe – it was rightly regarded as not only beautiful but among the best on the continent.

“It gave the people dreams,” said Miltos Logiadis, the hall’s artistic director. “For the first time we not only had the chance to hear the Berlin Philharmonic and other world-class orchestras, we could create music, perform in an auditorium like this, make ourselves heard and make ourselves better.”

No other place, he said, had played such a seminal role in educating and sponsoring Greeks in the art of the great classics. “This crisis has been a sudden death, like a war without a fight, a complete catastrophe. And how can a society live without culture?”

Soft-spoken and mild-mannered, Logiadis is a professional conductor recently brought in with Nicholas Theocharakis, a former finance ministry general secretary and the Megaron’s chairman, to turn the body around.

At the time of their hiring, the Megaron’s electricity bill alone exceeded €3m and had not been paid since 2013. Staff morale was at an all-time low, with salaries slashed by a third. And performances depended to great degree on the largesse of a single donor – an anonymous tycoon with a fondness for classical music who has taken to bankrolling concerts in the Athens hall.

It was against this backdrop that the state – itself reliant on rescue loans – bailed out the Megaron to the tune of more than €100m when it filed for bankruptcy in March. Arrears of more than €14m – mostly in unpaid bills to performers and suppliers – were also covered by the state budget.

But many in the ruling leftwing Syriza party were ideologically opposed.

“Although like the pupil in our eyes we must protect the Megaron, it is still in dire straits,” said Theocharakis. “The state is fed up. We are entirely reliant on a subsidy which has been cut from €12m to €3m.”

Racked by debt, the Megaron is in many ways the story of contemporary Greece. The vision of one man – the late media mogul and aesthete Christos Lambrakis – it was decided a decade after it first opened its doors that the hall should expand.

Riding the wave of optimism that preceded the 2004 Athens Olympics, when economic growth showed no sign of abating and the country seemed set to assume a leading role in the region, two loans worth €250m were taken to construct an opera house and conference centre in a subterranean building abutting the original concert hall. In the case of both loans, the Greek state acted as guarantor.

“Back then the pre-crisis value of the Megaron itself was €800m. Now nothing in Greece, save the Acropolis, is worth that amount,” said Theocharakis, adding that the hall still owed millions of euros to tax authorities, social security funds and construction companies. “Even now, it’s going to take a lot of effort to survive.”

For critics who see the Megaron as a pharaonic construction – a mirror image of the lust to expand in better times – it is a case of just deserts. The Greek culture ministry’s entire budget is about €100m – less than half of what it was before the nation’s disastrous economic crisis erupted in 2010. Victims, say opponents, have been legion.

But the charge of elitism has also come to haunt the Megaron. Many murmur that the leftist-led government, driven by an innate hostility towards the rich, is deliberately withholding funds for an institution that from the outset has been widely supported by wealthy Athenians. “Those charges are not entirely untrue and we are paying the price,” said Logiadis. “But the bottom line is the Megaron now belongs to the state and the state should do whatever it can to save it.”

The German-trained composer is now in the challenging position of having to devise an artistic programme that is both high- and low-brow and will keep the house full. Ticket prices have been reduced; more ballet, dance and experimental music introduced, and cooperation with other cultural entities increased.

The appearance of another cultural centre, which has been funded by the Niarchos Foundation and will also house the National Opera, has added to the pressure. The charity accepted under an agreement reached years ago to relinquish control of the complex and hand it to the Greek state, which it will do by the end of December. Its own operating costs have been estimated at €16m a year.

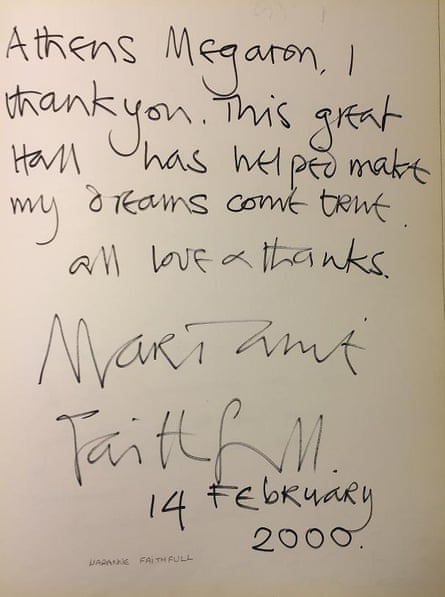

But the Megaron has found solace in artists – those drawn to the acoustic intimacy of its great hall and warm audiences. A book of impressions – affectionately referred to as the Libro d’Oro (golden book) by staff – is brimming with testimonials from performers as diverse as the Chinese concert pianist Lang Lang and American conductor Michael Tilson-Thomas.

Orchestras regularly perform at reduced rates. The renowned Argentinian pianist Martha Argerich wanted no money at all, instead insisting her fees went to the Athens Camerata. “Athens Megaron, I thank you,” wrote the English singer Marianne Faithfull after a Valentine’s Day show in 2000. “This great hall has helped make my dreams come true.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion