Adapting a book is a sure-fire way of discovering its strengths and weaknesses. Its plot must prove truly dramatic; dialogue must not only ring true but reveal character and advance the action. Robert Louis Stevenson’s South Sea Tales, broadcast this weekend starring David Tennant, are my 10th foray into adapting for Radio 4’s Classic Serial slot – after novels by Edith Wharton, Dodie Smith and John Wyndham – and I have never felt more privileged to be let loose on another writer’s work.

Both The Beach at Falesá and The Ebb Tide (novellas, in fact, at 70 pages and 131 pages respectively) were written while Stevenson lived in Samoa, from 1890-94, in the final years of his short life. He brought to them all the literary skills he had developed over his career as a bestselling writer, but beyond technique and confidence, these tales have a savage political and moral engagement, a real-world vision, and a black humour that is more distilled here than in anything else he wrote.

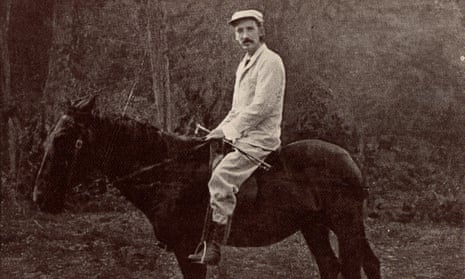

Stevenson and his wife, Fanny, set off for the South Seas in 1888, when he knew he was under sentence of death. He’d been suffering lung haemorrhages for years and doctors advised a warmer climate. Exploring the islands gave him a new energy and engaged his passionate curiosity about the islanders, both colonisers and colonised. From the start, his attitudes to the indigenous people, who included cannibals, differed widely from those of most other Europeans. In his journalism about his travels, he reveals that he found many resemblances between them and Scottish highlanders and islanders of the 18th century:

In both cases an alien authority enforced, the clans disarmed, the chiefs deposed, new customs introduced, and chiefly that of regarding money as the means and object of existence … Hospitality, tact, natural fine manners and a touchy punctilio are common to both races: common to both tongues the trick of dropping medial consonants …

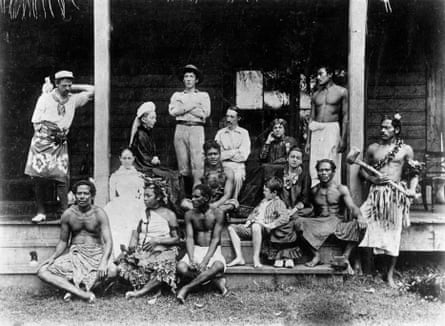

Stevenson, Fanny and numerous relatives, visitors and Polynesians settled in an estate he named Vailima in 1890. He learned to read and speak the language. His increasing knowledge of, and involvement in, island politics, and his back-breaking work clearing paths through the jungle on the estate, fed into the fiction he wrote there. It was fiction so different from Kidnapped or Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde that his fans were dismayed, and Oscar Wilde wrote: “I see that romantic surroundings are the worst surroundings possible for a romantic writer.”

The Beach at Falesá tells the story of trader, Wiltshire, who is welcomed by another white trader on the island, Case, and offered a native wife, Uma. Case organises a grotesque parody of a wedding between Wiltshire and Uma, and feigns ignorance when Wiltshire finds himself instantly tabooed. No one on the island will trade with him. Gradually the truth emerges. Case has driven other traders from the island and even helped to kill a couple of them; the natives are in thrall to him, convinced he has devilish powers. Blunt, racist, atheist Wiltshire is an unlikely hero, but he is revealed to be both decent and courageous, and he falls in love with Uma, who is herself extraordinarily brave. Stevenson’s depiction of a strong, intelligent native woman is based on observation; in his journalism he reports that power in Samoa resided in rank, not gender.

It is Wiltshire who relates the story, opening with: “I saw that island first when it was neither night nor morning. The moon was to the west, setting, but still broad and bright. To the east, and right amidships of the dawn, which was all pink, the daystar sparkled like a diamond ...”, beautifully setting up the conflicts to come: night and day, dark and light, death and love. In a letter to his close friend Colvin, Stevenson called it “the first realistic South Seas story; I mean with real South Sea character and details of life”. It is fascinating to trace that realism back to actual events described in his and Fanny’s journals. In the Gilbert islands a native woman proudly displayed her marriage certificate to them. It stated that she was “married for one night” and that her white “husband was at liberty to send her to hell the next morning”. Uma’s marriage certificate, which she guards jealously, contains the same wording, and as Wiltshire falls in love with her it gnaws at his conscience sufficiently for him to request a proper marriage by a missionary. Similarly, Case’s “Devil-Church” in the bush terrifies natives with a glowing devil’s face, just as Fanny frightened thieves away nightly from her piglets by painting a hideous mask in luminous paint on a cask lid.

Stevenson’s letters record that The Ebb Tide, published two years later, was painfully difficult to write, and although it still contains glints of comedy, the story is dark indeed. Three down-and-outs are malingering on the beach at Papeete, scrounging food from Polynesian sailors. Davis is a disgraced US sea captain, Huish a thieving cockney, Herrick an Oxford-educated failure. Their fortunes are reversed when Davis is given captaincy of a schooner that no one else will touch because the captain and mate have died of smallpox. Our three desperadoes set sail with a Polynesian crew, and are soon tucking into the cargo of champagne and squabbling horribly. Their plans to steal the ship are thwarted by a shortage of stores, and they put in at a private island where they find a “huge, dangerous-looking fellow. His manners and movements, like fire in flint, betrayed his European ancestry”. He is Attwater, the most villainous villain you are likely to meet this side of Kurtz (I am not alone in thinking Joseph Conrad may owe the older and, at that time, more successful Stevenson something of a debt for Heart of Darkness). Attwater has combined missionary zeal with ruthless efficiency in running a pearl fishery, and 29 of his 32 slaves have recently died of smallpox. The dinner to which he invites his three guests is a masterpiece of suspense, over which he presides with veiled menace. “A cat o fhuge growth sat on his shoulder purring, and occasionally, with a deft paw, capturing a morsel in the air.” (A prototype for Blofeld?) Here’s a morsel of dialogue from that dinner. The conversation has turned to Attwater’s method of slave-driving.

“Wait a bit,” said the captain. “I’m out of my depth. How was this? Do you mean to say you did it single‑handed?”

“One did it single-handed,” said Attwater, “because there was nobody to help one.”

“’Ope you made ’em jump,” said Huish.

“When it was necessary, Mr Whish, I made them jump.”

Herrick, the Hamlet of the piece, paralysed by indecision, listens in silence. Note the captain’s drowning figure of speech, Attwater’s upper-crust “one”, and his insulting mispronunciation of Huish’s name. As for Huish, his accent is written in.

Snobbery, the greed and cruelty of white people, religious hypocrisy and the casual destruction of native cultures and lives are all grist to Stevenson’s mill. Yet he succeeds in exploring these dark themes in tales of high drama and suspense, with wicked humour and an infectious open-heartedness towards all his characters. They are exposed, but rarely judged.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion