This colourful, exuberant, brilliantly detailed account by Jerry White is the latest in a long list of irreplaceable books about London, all written as if the author were personally remembering what he describes rather than excavating it. This one, anatomising one of London’s most famous prisons, the Marshalsea debtors’ jail, bears a striking dedication, which remains at the heart of everything that follows: “To debtors everywhere.” His opening chapter etches a striking, Hogarthian panorama of the day-to-day experience of defaulters through the centuries, confronted with implacable creditors, back-street attorneys (the notorious pettifoggers), corrupt lawyers hiking up their fees, a callous judiciary and brutal jailers. And debt was no respecter of class: Daniel Defoe, Richard Steele, Henry Fielding, Tobias Smollett, Dr Johnson, Oliver Goldsmith and John Cleland all suffered its depredations.

Never once does White, as he describes the vicissitudes of the prison itself, lose sight of the central sickening reality of debt – recurring, self-fulfilling, inescapable debt – as it affected the individual. The crushing hopelessness of the debtor’s situation is evoked in the epigraph to the book, a quotation from the entry on “Hard-up, floored, broke” in a late-19th century slang lexicon of which this stream-of-consciousness extract gives a flavour: “Dead-beat; basketed; bitched; buggered-up; busted; caved-in; choked-off; cornered; cooked; done brown; done for; done on toast; doubled-up; flattened out; fluffed; flummoxed; frummagemmed; burst; fleeced; stony; pebble-beached; in Queer Street; stripped; rooked; hard-up; hooped-up; strapped; gruelled.”

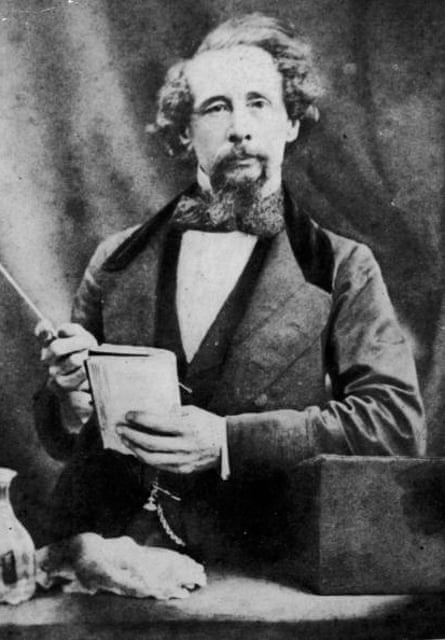

The Dickensian vitality of this vocabulary of despair is testament to the ability of the human spirit to rise above misfortune, embodying the sort of trench humour much in evidence in White’s pages: the inmates habitually referred to their place of confinement as “this inchanted Castle”, “these Mansions of Misery”, and even “the College”. Mention of Dickens reminds us that if we know the name of the Marshalsea at all now, it is because of the immortality conferred on it by the great novelist in a series of works successively transmuting his childhood experience of his father’s incarceration there, through the high jinks of The Pickwick Papers at the beginning of his career to painful autobiographical self-revelation in David Copperfield, and culminating, in his grim maturity, with Little Dorrit’s vision of the world as a prison. One of many remarkable aspects of Mansions of Misery is its majestic progress through social history into literature, from sharp description of the reality of the prison and its inmates to a concluding celebration of its metaphorical existence, achieving by the end a quite extraordinary resonance.

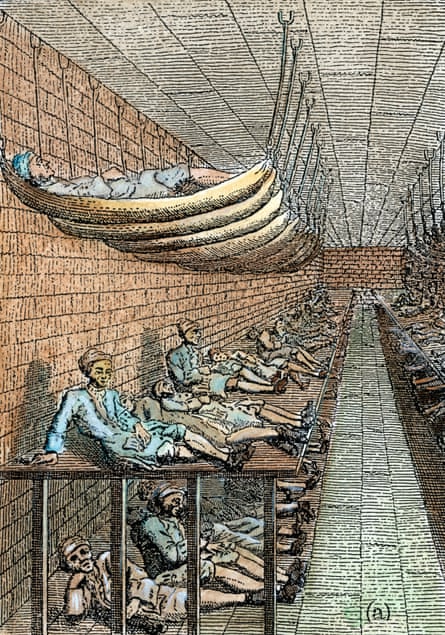

The Marshalsea was located in Southwark, the historic location of theatres, bear-pits and whorehouses, and was, to begin with, beyond the jurisdiction of both the cities of London and Westminster. It wasn’t until the mid-17th century that it settled into being exclusively a debtors’ jail. Then it was full to bursting: people could be thrown in for owing as little as sixpence. In which case, he or she was charged in “Execution”, which immediately increased the indebtedness to £1 5s 6d, making it much less likely that the prisoner could ever get out. “More unhappy People are to be found suffering under extream misery, by the severity of their creditors,” one commentator noted, “than in any other Nation in Europe.”

The life of the jail offered, as Smollett noted in The Adventures of Roderick Random, a perfect microcosm of the world outside. Apart from anything else, the prison was divided into two: the haves and the have-nots, designated common-side and master-side. For a sense of what life was like for the haves, White has unearthed a star witness from the first half of the 18th century, John Baptist Grano, a musician – trumpeter, wind player and composer – of Italian origin, a convivial sort, an intemperate drinker and a socialite whose upwardly mobile aspirations had finally landed him in the clink. His wonderfully candid A Journal of My Life Inside the Marshalsea depicts a highly agreeable life. He regularly dined with the prison turnkey, William Acton, with whom he became very friendly – even attending his son’s christening.

He shared a pleasant, clean cell – and indeed a bed – with one Adam Elder, and after drinking a number of bottles of good wine, once Elder had turned in for the night, “I sat up, sounded a dozen airs on the trumpet, Wash’d my Manhood, Legs and Feet, read a little and went to bed between 12 & 1.” Some nights Elder would pay the maid (a prisoner from the common-side) to have sex with him. Elder made love, uninhibitedly, on his half of the bed while Grano attempted to sleep on the other. But such mild inconveniences were rare; Grano’s rich friends made sure that life was tolerable. On one occasion, Lord Leeds sent in “motton, pigs and fowls”, which Grano sent out to be cooked and dressed. He was able to teach in prison, among his pupils being two young black trumpeters, and he continued to compose prolifically, notably a bassoon concerto, In Five Moods.

Life on the poor side of the prison was another story altogether, recorded in a prison memoir with the sensational title of Hell in Epitome: or, A Description of the M-SH-SEA. That title was fully justified when Grano’s chum, Acton the jailer, a man of mercurial moods and violent contrasts, was brought to trial for the deaths of four prisoners. For a sizable sum of money Acton had sublet the running of the prison from the deputy marshal; if he defaulted on his dues, he would be thrown into prison himself. So it was greatly in his interest to extract any money due to him from the prisoners, whom he described as “Sons of Bitches”.

News of the brutality at the Marshalsea finally provoked a parliamentary inquiry, which uncovered atrocious conditions: one defaulting prisoner was locked up with two dead bodies; he stayed with them for six days, “in which time the Vermin devoured the flesh from their faces, eat the Eyes out of the Heads of the carcasses, which were bloated, putrifyed, and turned green”. Other prisoners were assaulted with a hellish implement: “a bull’s pizzle, dried hard as teak, some three or four foot long with a swollen end like knobkerrie, a favoured weapon of butchers who were slaughtermen”. Astonishingly, and to the disgust of reformers everywhere, Acton was cleared.

Reform slowly won the day: the establishment of the Society for the Discharge and Relief of Persons Imprisoned for Small Debts in 1773 hugely improved the situation, ensuring that charity reached its proper destination: a majority of prisoners now left after a short stay. Before long, the crumbling, fetid old prison was demolished and a new one built on the site: this is the Marshalsea where John Dickens was confined in 1824 when Charles was just 12, and where he stayed for 14 weeks.

The whole family, apart from Charles and his sister Fanny, came to stay with them, including a maid. In addition to the pleasant rooms, there was an alehouse and a snuggery. “In every respect indeed but elbow-room,” Dickens told his biographer John Forster, “the family lived more comfortably in prison than they had done for a long time out of it.” Above all, they were free from the loud knocking at the street door, the abuse shouted up at them from the pavement for all the neighbours to hear. Thanks to the provisions of the Insolvent Debtors Act, John Dickens emerged from the prison and stepped into immortal life as Wilkins Micawber.

But by the time Dickens wrote Little Dorrit, there was no place for such indomitable figures as Micawber: the picture of life in the Marshalsea is one in which, as White nobly writes, the prison stands “for the iron girdles of money and power binding the whole of contemporary society in a straitjacket that stifles initiative, creativity, mutual affection, even humanity itself”. When William Dorrit is finally released, a broken man, he is closely watched. “As they eyed the stranger in passing, they eyed him with borrowing eyes – hungry, sharp, speculative as to his softness if they were accredited to him, and the likelihood of his standing something handsome.” The Marshalsea ceased to be a prison in 1842; on the site has long stood a public library. Justice, finally, has been done.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion