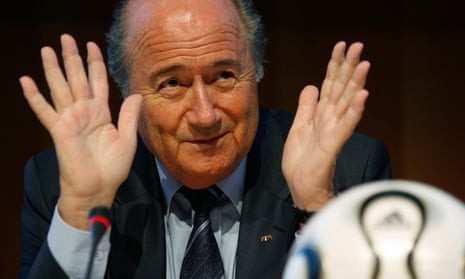

For Sepp Blatter, whose span at football’s world governing body has bridged an extraordinary 40 years, 17 as president, nothing has hurt him like the manner of his leaving. His recent, increasingly frantic pronouncements and a “small emotional breakdown” last month have been the closing moments of a flailing emperor, unable to believe his power has drained away. At 79 he remains bemused that forces of opposition he associates with devils and demons have assailed him right into his Fifa HQ on his hill in Zurich and banned him from his own kingdom.

Blatter prolonged his presidency for so long, breaking promises to step down in 2006, 2011 and this year, because he became wedded to Fifa, speaking of the organisation as his fiancee, and believed he was indispensable to its workings. It was planned to end, if at all, at a date of his choosing, with international plaudits and preferably a Nobel prize – never as a culprit found guilty of wrongdoing by an ethics committee he himself introduced.

To his supporters, of whom there do remain many within the dysfunctional “family” of football’s world governing body, Blatter is credited with a great legacy of developing the game globally, since he took on that job when he joined a broke, parochial administration as a charming, kipper-tied thruster in 1975. For football associations in Africa and other developing nations, the billions Blatter has delivered in development funds, and the expansions of the World Cup and other Fifa tournaments, opened up football.

They still remember as colonialist the rule of Sir Stanley Rous, Fifa’s English president until 1974, and the notorious accommodations he made with the South African FA during the apartheid era. Some agree with Blatter’s deep resentment of the US attorney general, Loretta Lynch, characterising Fifa as a mafia-like racketeering organisation, pointing out that the roster of defendants now indicted for corruption were all involved in American football confederations. The investigation, after all, started with the Inland Revenue Services chasing up the unpaid taxes of Chuck Blazer, who raked in the bribes from his base in central New York.

To Blatter’s vehement critics – including some respected senior figures in European football who really loathe him – the ban by an ethics committee, which has found its backbone, represents the grubby reality of Blatter’s methods finally, far too late, catching up with him. To them Blatter was the Machiavellian master of power politics at Fifa, learning from his years working for the Brazilian João Havelange, who supplanted Rous and maintained his grip as president for an extraordinary 24 years until 1998, when Blatter won the election to succeed him.

Havelange, who took millions in bribes and kickbacks from Fifa’s deals with the marketing company ISL, demonstrated that a president needs a majority of the member football associations to vote for him. If he is then to control what the organisation does, he also needs support within the 24-man executive committee, principally representatives of the six continental confederations.

To the critics Blatter made unholy pacts with the multiple crooks in the executive committee who supported him: Jack Warner, the Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football (Concacaf) president, now banned from football for life and indicted by the US authorities for alleged corruption; Blazer, Warner’s Concacaf general-secretary who has pleaded guilty in the US to multi-million dollar corruption and tax evasion and turned supergrass; Nicolás Leoz, the former South American Confederation (Conmebol) president who took bribes from ISL and is now also indicted in the US; Ricardo Teixeira, president of the Brazilian Football Federation who also took ISL bribes and is similarly now indicted; and the Qatari Mohamed bin Hammam, Blatter’s principal backer in 1998, now also banned for life from football following corruption allegations. Julio Grondona, the late chairman of the Argentinian Football Federation and of Fifa’s potent finance committee which awarded Blatter the presidential salary never made public, always supported him, too.

Critics have long also argued that the Goal and $250,000 annual football assistance programmes to FAs around the world are tainted, effectively operations to buy support from the developing countries. Fifa itself points to more than $2bn having been paid in development funds since Blatter implemented the programmes immediately after his 1998 election and argues that, despite some inevitable corruption locally, solid improvements in global football infrastructure are self-evident. The organisation also argues that auditing procedures have been tightened, stating last month that 28 football associations had their funding blocked for breaching the required standards.

Emmanuel Maradas, the former editor of African Soccer magazine who has also worked in various roles for Fifa, says the dispensing of so much money to impoverished football associations did secure Blatter support and was inevitably prey to some corruption. However, he says Blatter is regarded as having genuinely wanted to benefit African football and that he has produced a huge, concrete legacy.

“In Africa they remember Sir Stanley Rous and that before Blatter they had literally nothing,” Maradas says. “Blatter promised in 1998 to provide financial assistance and he did so immediately. Since then in many countries there has been great progress, some fantastic projects, there are FA headquarters, pitches, academies. In Africa they say of Blatter: ‘He delivers,’ and that is why they support him.”

The message of defiance Blatter sent in his letter last week to the 209 football associations which make up Fifa’s worldwide constituency was a classic proclamation. He pleaded innocence of any wrongdoing, partly by pointing to arcane internal committee processes, and bewilderment that Fifa’s own procedures, the ethics committee, have finally come for him. There was the trademark florid hyperbole, often given religious expression, in this case his claim that the ethics committee chaired by two lawyers “reminds me of the inquisition” – which he did not expect. Characteristically Blatter pointed to Fifa’s development work around the world, while proclaiming his adherence to the homespun values of his remote, rural Catholic Swiss upbringing.

“These are values passed on to me by my parents which I have always lived by, both in a professional and a personal capacity,” he wrote, then listing principles oddly limited to two: “Never accept any money which you have not earned” and “always pay off your debts”.

Yet in the acts for which he has been banned by Fifa and remains – to his great shock and hurt – under criminal investigation in Switzerland where he has always previously felt comfortable he is not accused of receiving money. Both, in fact, are the opposite of improperly receiving money; he is accused of improperly giving money, to people who were his political allies at Fifa: £1.35m to Michel Platini, and an overly generous TV contract to Warner. For all that he resents it so bitterly there is something fitting about this end, because these deals are guides to the complaints constantly made against Blatter without previously sticking, that he enabled others to get rich and so remained in power himself.

The first allegation made by the Swiss Attorney General, Michael Lauber, in September, that in 2005 Blatter gave Warner a wildly favourable TV rights contract, points to the many years in which Warner, and others, were alleged to be hugely enriching themselves from football, while supporting Blatter in the executive committee.

Platini’s meteoric ascent as an administrator after his true greatness as a player, and now his precipitous fall, traces precisely the arc of his involvement with Blatter and the games the president played with him. Blatter drew Platini into Fifa politics in 1998, recruiting the former France captain to add stardust and vital European support to Blatter’s candidacy for the presidential election against the respected Lennart Johansson, the Swedish then president of Uefa.

Blatter’s victory in that Fifa election, 17 years ago, was accompanied by loud accusations that Bin Hammam, the Qatari executive committee member who was Blatter’s principal backer, had paid cash for some African delegates’ votes. Blatter and Bin Hammam have always denied that. Years later Bin Hammam was exposed in emails leaked to the Sunday Times for paying African delegates cash before the 2011 presidential contest, when he challenged Blatter, as well as paying Caribbean delegates $40,000 each in a Trinidad hotel room, which led to his removal from the election. Johansson has told the Guardian that the current excavation of Fifa’s financial workings should include a full investigation of the 1998 allegations:

“I welcome what the American investigators are doing at Fifa,” he said. “I believe they get to the bottom of things when they investigate, and they should find out about 1998. I knew the kind of person Sepp Blatter was and I tried to attack him but he had other people’s support.”

It was right back then, after his election win over Johansson, that the new president Blatter gave Platini, after his support, the job at Fifa as his “football adviser”. According to both men, they made that verbal “gentleman’s agreement” about the money, which has now brought the pair of them crashing out of football itself. For a man of Platini’s football pedigree but no professional or administrative qualifications, the 300,000 Swiss francs (£203,500) formally agreed as his adviser’s salary was not to be enough. Blatter, both men say, agreed without putting in writing that he would also pay Platini a further 500,000 Swiss francs (£339,000) a year – at some indeterminate time in the future.

The four years Platini spent sitting at Blatter’s side set the French hero on the path thousands of former players have always coveted: to proper, paid, administrative work in football. Almost from the beginning of their alliance Platini believed he had a pact with Blatter and his blessing to succeed him ultimately as Fifa president. How much did the extra 2m Swiss francs (£1.35m) for four years’ “gentleman’s agreement” salary top-up, a debt he could call in, keep Platini tied to Blatter? Certainly, more than nine years after leaving Fifa’s employ in 2002, despite falling out with Blatter, Platini never forgot he was owed the money; ultimately sending his invoices in, catastrophically for him, nine years later.

The loathing Johansson and his allies have for Blatter extends to his masterful manipulation of the election for Uefa president in 2007. For the preceding two years Blatter let it be known that he supported Johansson, who was recognised to have integrity and to have done a fine, professional job. That backing from the Fifa president deterred other candidates from stepping forward. Then in late 2006 Blatter switched and said he would support Platini, whom he still held close as his ally then. Platini, with that support, won and Johansson felt deeply betrayed, the Uefa chief executive, Lars-Christer Olsson, resigning in protest.

The natural rivalry between Fifa and Uefa quickly asserted itself and Blatter, in a highly telling gripe, claimed to have felt “sidelined” at the opening ceremony of the 2008 European Championships in Switzerland, because his VIP seat was eight along from the centre. More recently Blatter revealed his exasperation with Platini for backing Qatar to host the 2022 World Cup after, Blatter said, a majority in the executive committee – before the bidding process concluded – had predetermined they would select Russia for 2018 and the US for 2022.

By the time of the cataclysmic Qatar vote in December 2010 Blatter had already gone back on his promise to stand down as president the following May. Bin Hammam believed he had an agreement to be the anointed successor and felt betrayed. He tried to persuade Platini to stand against his old ally but Platini never believed he could beat Blatter.

Through so much time and turbulent business in Zurich, Nyon and around the world, Platini still clearly always remembered he had that £1.35m promised to him by Blatter. Only Platini himself knows why, nine years after leaving the job, he suddenly invoiced for it, but the timing – February 2011 – is devastating. Platini decided not to stand against Blatter, weeks later Bin Hammam declared as a candidate, but Platini, head of 54 European associations with votes in the election, backed Blatter. Platini appears to believe that the £1.35m genuinely had no influence on his thinking; he considered it money legitimately owed, as Blatter says he did. Yet the whole thread, stretching right back to Platini’s doe-eyed entry into Blatter’s world, spins a tale illustrating Blatter’s mastery of politics.

He said he would stand down again when his fourth term was up this year, and Platini, believing his appointed time had come, felt betrayed when the old operator went back on his word again. Yet this time it was once too many. The Swiss authorities agreed to make multiple arrests, on US indictments, of Fifa executive committee members and officials gathered for the coronation in the luxurious heart of Zurich itself. Lauber began an investigation into the Russia and Qatar bidding process voted on by Blazer, Warner, Leoz, Teixeira, Bin Hammam and others now banned from football, seizing financial assets and mountains of communication.

That Blatter was still voted in as president days later emphasised the immunity of his organisation from shame, and the depth of support he has accrued. But even his ruthless knack of silencing critics could not stem a crisis on this scale. He was somehow persuaded by those close to him, including his daughter Corinne, to step down but still sought to control the process by choosing the date of his leaving, February next year. The Platini invoices, lying in the Fifa offices, finally did for that elegant exit, leading to his suspension and departure as a banned man, a horror unimagined all these years.

Jérôme Champagne, the former French diplomat who joined Fifa as Blatter’s international adviser in 1998, worked in football development and is now a candidate to succeed him, has said he believes Blatter’s global legacy has to be recognised and that “history will judge him better than the news”.

That could turn out to be true but from the grinning executive who joined a fusty Fifa in 1975 to the shaky president expelled from the multibillion dollar world governing body 40 years later, no account of Sepp Blatter will ever be entirely straightforward.