Many tech entrepreneurs will promise you the moon. Naveen Jain is hoping to deliver it.

Five years ago, the founder of dotcom search giant InfoSpace set his sights on actual space, creating Moon Express, a startup with the then outlandish goal of mining the moon for minerals.

Last August, Moon Express became the first private company to receive permission from the Federal Aviation Administration to land a craft on the lunar surface. By the end of 2017, it plans to launch its first exploratory mission to our nearest neighbor in the solar system.

If successful, Jain’s company may collect the $25m Google Lunar XPRIZE, which has been promised to the first private firm to land on the moon, travel at least 500 meters and transmit high-definition images back from the surface.

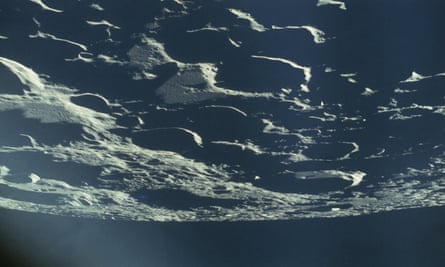

Jain isn’t proposing to drill holes in the moon or strip-mine Mons Huygens which, at 18,000 feet, is the tallest peak on the lunar landscape. Most of the treasure he seeks is on the ground, deposited by millions of meteors that have struck the lunar surface over the past 4bn years. And he hates the term “space mining”.

“Mining has such a negative connotation, people think you’re drilling a hole and destroying things,” he says. “This is more like collecting or harvesting.”

But Jain’s ambitions are much bigger. Like other tech billionaires entering the space race, he hopes to lower the costs of space travel, help enable the colonization of the moon and later Mars – and make a tidy profit along the way.

“To rephrase John F Kennedy, we choose to go to the moon not because it is easy, but because it is a great business,” Jain jokes. “The second reason is the moon is the perfect training ground for going to Mars.”

Robots and snowballs

Moon Express is not the only company aiming to get a piece of the gold rush that’s about to happen hundreds of thousands of miles above our heads.

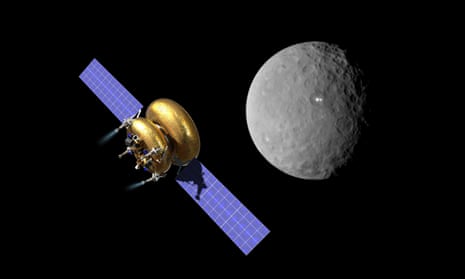

Deep Space Industries (DSI) is building autonomous spacecraft that can extract materials from asteroids. It expects to launch its first experimental mission in 2017, and send its Prospector 1 autonomous craft to a near-Earth asteroid by the end of the decade, says Meagan Crawford, vice-president of strategic communications for DSI.

Planetary Resources – a company backed in part by Google’s Larry Page and Eric Schmidt, as well as the government of Luxembourg – is also developing technology that will allow it to begin exploring asteroids starting around the year 2020.

What’s out there worth mining? Every element known to mankind, in virtually infinite amounts.

In 2014, the financial services site Motley Fool estimated the mineral wealth of the moon to be between $150 quadrillion and $500 quadrillion – enough to create 500m billionaires. Add in the riches found inside asteroids, and the sky is literally the limit.

The moon, for example, is abundant in Helium-3, an extremely rare element on Earth that could theoretically be used as fuel in future nuclear fusion plants. Asteroids are typically chock full of iron, nickel, cobalt, platinum and titanium.

But the real gold, at least initially, is water. Many near-Earth asteroids are abundant in carbonaceous chondrites that contain a lot of ice, says Crawford. Think of an enormous dirty snowball, winging around the sun at 55,000 miles an hour. Now imagine landing a robot on that snowball that can extract the ice and haul it away.

“Water is the fuel of space,” Crawford says. “The constituent parts are liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen – that’s rocket fuel. We’re also working on technology that uses superheated water itself as a propellant, so you don’t have to separate the oxygen and hydrogen.”

More than 90% of the weight of modern rockets is the fuel, Jain notes. As companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin begin launching reusable vehicles, fuel becomes the biggest cost of going into space. The less of it you have to carry, the cheaper space travel becomes.

In this scheme, asteroids would essentially be gas stations, allowing ships to carry just enough fuel to emerge from Earth’s gravity well, then fill up their tanks as they head toward their final destination.

Of course, water is also useful for drinking, hygiene, irrigation and extracting oxygen for the Mars colonies Jain, Elon Musk, and others are so keen on creating. And it’s a more effective shield against solar radiation than lead. Future Martians could conceivably be living inside domes, insulated by a protective layer of water.

Once DSI has figured out how to mine ice, the company plans to begin extracting ore – not for hauling back to Earth, but to help space manufacturers build structures in space that are too big and expensive to cram inside a rocket.

Likewise, Planetary Resources aims to distribute water and metals in space, where it will be far cheaper than hauling it up through Earth’s gravity well.

“Our business is about obtaining resources and using them pretty close to where we got them,” says CEO and co-founder Chris Lewicki. “With space travel, you need a really big rocket to take along tiny amounts of things. Ultimately, we want to be able to send more people and bring less stuff.”

Is this really legal?

Can any American citizen just go into space, latch on to an asteroid or moon, and start hauling back rocks? Yes they can, thanks to the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, signed by President Obama in November 2015.

While the law stipulates that no nation can claim ownership of an asteroid or other heavenly body (in accordance with the Outer Space Treaty of 1967), US companies will be able to extract and own any materials they find in the great beyond.

Other countries have yet to adopt similar treaties, though Luxembourg is close to passing similar legislation, Crawford says.

“We expect in the next few years there will be several bilateral and multilateral agreements that will settle on an international convention for how this is going to be regulated, similar to how deep-sea mining is handled today,” she says.

‘Shiny things in a stream’

But for now, space mining is an industry still waiting for its moment. Even with SpaceX and Blue Origin slashing launch costs, sending anything into space remains a radically expensive proposition. The market for raw materials to build moonbases or refueling stations to enable busloads of Mars colonists has yet to materialize.

While all three mining companies are planning launches next year, none expect to begin extracting anything of value from space until well into the next decade.

“The cost of space transportation will have to come down drastically before it becomes economical to transport minerals to Earth from asteroids,” notes William Ostrove, aerospace and defense analyst for Forecast International. “If colonies on the moon or Mars become a reality, it may be cheaper to mine resources on asteroids rather than transport them from Earth. But that’s also decades away.”

Even then, the first efforts are likely to be modest, says Lewicki. “Gold mining didn’t start as a massive industrial operation with complicated machinery and complex supply chains,” he says. “It started with a Levi’s-wearing gentleman looking for shiny things in a stream and picking them up. Space mining is likely to start out as something pretty simple as well.”

In the meantime, Planetary Resources has begun launching compact Earth observation satellites for use in agriculture, environmental monitoring and energy industries. It allows the company to generate revenue while it waits for the space mining industry to take off, and gives it a chance to test and refine the technology it will use to detect water and minerals in space.

“Lots of people got wind of the gold rush, cashed in their fortunes, got on a wagon headed west and staked their claims,” says Lewicki. “And most of them failed. Nine out of 10 startups fail as well. Success isn’t assured for anyone in this business, but the opportunity is clearly there.”

The ‘Pokémon Go of the moon’

Like Bezos, Musk, and other tech billionaires, Jain is hoping to bring down the marginal costs of space exploration low enough to enable entrepreneurs to come up with solutions not yet imagined – just as the PC, internet and iPhone spurred innovation no one at that time could foresee.

“When Steve Jobs asked people what apps they wanted to see on the iPhone, not a single person said ‘Hey, I would like to throw the birds at the pigs,’” says Jain. “But that’s what people did. Once we land there, someone else will build the Angry Birds and Pokémon Go of the moon.”

And, like Musk, he’s trying to use his personal wealth to ensure the future of humanity by enabling it to expand beyond our planet’s fragile boundaries.

He’s also a hopeless romantic.

“Moon rocks themselves may be the most valuable thing – they are beautiful,” says Jain, who gave a moon rock to his wife for their 25th anniversary, and claims to own the largest private collection of meteorites in the world.

“They could replace diamonds. You simply change the paradigm: ‘Anyone can give her a diamond. If you love her enough, you’ll give her the moon.’”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion