By Jaideep A Prabhu

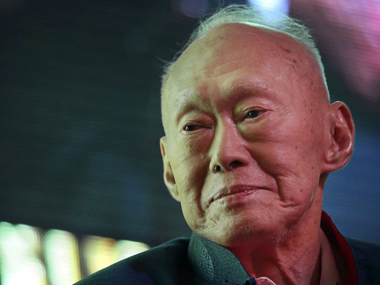

In the early hours of 23 March 2015, Lee Kuan Yew passed away at Singapore General Hospital; he was 91. Having dominated Singapore’s politics for over five decades - as prime minister from 1959, even before the city state’s independence from Malaysia, to 1990, and then in a ministerial capacity until 2011 - Lee seemed virtually immortal. In his time at the helm, Lee transformed Singapore from a tiny tropical port city with no natural resources and a multicultural population to a glistening first-world metropolis with one of the highest per capita incomes in the world.

Lee was truly one of the great men of his era, though of a different sort from most leaders. He did not command vast armies nor did he posses enormous wealth; he did not seek the limelight nor did he shun it. In its early days, Singapore was as ridden with ethnic conflict (Maria Hertogh - 1964 Race Riots, 1969 Race Riots), linguistic differences (Malay, Tamil, English, Mandarin), and poor literacy as any of the other new post-World War II countries. Yet Lee was able to mould a functioning state from these disparate elements and foster prosperity among its citizens.

Lee’s remarkable record is even more poignant when juxtaposed with the results of the policies of the galaxy of new world leaders that emerged in the decolonisation of the 1950s and 1960s - Jawaharlal Nehru, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Sukarno, Kwame Nkrumah, Fidel Castro, Mao Zedong. Not one surpassed Yew in providing their citizens education, sanitation, the rule of law, employment, infrastructure, and security. Or aspiration. Singapore is today an inspiration for the countries in the region.

What marked Lee out from his early days as prime minister until his death was a clarity of thought and directness of speech few politicians ever exhibit. His utterances were always considered, never verbose, and substantial. Lee was never afraid to buck the trend - he spoke and acted with conviction that came from careful thought rather than opinion polls or outside influence. His model of governance, though it has come under much flak, was a peculiarly Asian understanding of the political process that was at once liberal yet restrictive, democratic yet paternal.

Lee offered - unintentionally, perhaps - those who wished to emulate him a style of politics that was a palatable alternative to the European model, one in which liberty did not mean license and decorum was insisted upon in public life. Graffiti, slander, and a media that revelled in mockery and reporting the prurient was not tolerated but the press was not muzzled as one might expect in an authoritarian state. However, harsh libel laws kept most publishers on edge. In fact, publishing houses were made to issue special “management shares” that carried more voting privileges than regular shares and these were held by Singaporeans appointed by the government. This gave the government influence in the media without taking it over completely. The ministers of Lee’s party, the People’s Action Party, defended this measure by arguing that not all ideas were worthy of consideration and undesirable ideologies or philosophies could not be allowed to infect the people of Singapore. Lee kept the foreign press at bay, allowing them to report Singapore to the world and bring the world to Singapore but denying them the right to play a role as “invigilator, adversary, and inquisitor” of the Singaporean democratic process.

A famous example of Singapore’s libel laws is the case of lawyer and parliamentarian JB Jeyaratnam. Lee relentlessly sued his opponent over every act of libel until Jeyaretnam was declared bankrupt and barred from standing for elections for a while. When asked about the incident in an interview, Lee merely pointed out that the libel laws apply to him as well and no one had ever sued him for libel. Dignity in the public sphere trumped the freedom of expression.

Lee’s Singapore did not believe in equality , at least as it is normally defined in the West. In fact, the late prime minister unequivocally rejected the notion. However, the state provided quality education, free up to a certain level, to give Singaporeans the opportunity to better their lot in life. Citizens were equal before law but social equality had to come from the character, conduct, and effort of the individual.

Lee inculcated a spirit of meritocracy and elitism among Singaporeans. For him, it was essential that the best man for a job should do it; after all, the rulers must be beyond reproach in a paternalistic system. For the less competent and non-elite, these were labels worthy of scorn for they denied access to life on a grander scale. Lee was absolutely unapologetic about the unofficial class system in his country. Statecraft was serious business, he argued, and it affected the lives of all. Government could not be left to the whims of anyone who might be interested in the trappings of power.

Housing laws in Singapore enforced heterogeneous neighbourhoods: regulations dictated the approximate ethnic breakdown of each locality so that ghettos would not form. A ghetto of location transforms quickly into a ghetto of mind and could become a divisive force in Singapore. Harsh fines against litter, spitting in public, failure to flush public toilets, and even chewing gum were enacted to clean up the streets and waterways of the city state. A clean, law-abiding, and peaceful city would be a place of pride for the people, Lee thought, and it would also attract foreign investments. An excellent public transport system was developed to encourage commuters to give up private vehicles.

Some have criticised Lee’s Asian model on the grounds that Western liberal democracy can just as easily implement conservative policies if there is support for those ideas. Unfortunately, this does not grasp the full nature of Lee’s model which has at its core an unapologetic elitism. Lee did not believe that the common man was capable of always deciding in his best interest, let alone that of the larger society. In Lee was embodied the closest 20th century approximation of Plato’s philosopher king.

The greatness of Lee was that he recognised what was required for and of society. He unabashedly pointed out that none of the Western democracies were born liberal; there is no instance of liberal democracy having assisted in the development of any poor nation. While human rights organisations complained about Singapore’s authoritarianism and Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders gave Singapore a poor rating in their indices, Lee was forthright in declaring that he judged a system by how well it provides for its people’s needs, not by what some theoretician on democracy opined.

As the generation changed in Singapore, the mindset of the new youth changed too. Lee was sensitive to this transformation and stepped down from office voluntarily in 1990. “The time has come for a younger generation to carry Singapore forward in a more difficult and complex situation,” he declared in his letter of resignation. As Lee told one student at a National University of Singapore forum in 2009, the old generation built the country up, the next generation made it wealthy, and now it was for the youth to figure out where to go next. Lee continued to stand for parliament until the elections of 2011 when he finally retired from public life for good. For 21 years after his resignation from the highest post in the land, he served the people of Singapore, but in an increasingly less prominent role. He was senior minister until 2004 when he became minister mentor.

The new generation is indeed different from the one of their parents or grandparents. They do not know of dire poverty, desperation, or what it is to live in a flailing state. And thank the god for that. In this new era, Singapore has different problems - immigration, radicalisation, terrorism - that may require different solutions. Lee was traditional, perhaps, but he was not orthodox. He recognised that the era of his top-down governance was nearing an end and stepped down to make way for someone capable of handling the new times. Lee had done his part - he had set Singapore on a very firm footing. Only the next 50 years will tell if Singaporeans have learned Lee’s lessons well.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)