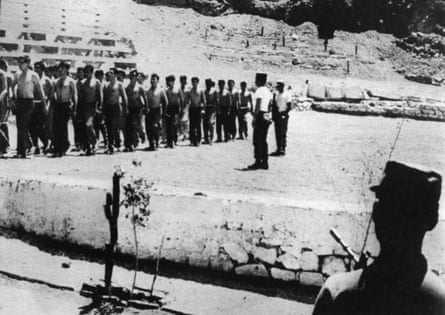

Many testimonies exist – legal, historical, political and human – to the horrors of the military coup and ensuing dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean general who died 10 years ago this week.

But as all Latin America recalls the man whose brutality defined an era, no record better captures the ethos of its suffering than the collection of music made, performed, heard and sung by prisoners in the network of centres for political detention and torture operated by Pinochet’s brutal regime.

Cantos Cautivos (Captive Songs) is a digital archive compiled by Katia Chornik, daughter of two opponents of the dictatorship who survived one infamous detention centre, which was named La Discothèque by agents of the Dina secret police because guards deployed loud music to torture their quarry, or as a soundtrack to the abuse. Chornik spent her childhood in exile, between Venezuela and France, returning to Chile with her parents by the end of the dictatorship. She studied violin and musicology in Chile and the UK.

Chornik put together the Cantos Cautivos project while working at Manchester University and in collaboration with the Chilean Museum of Memory and Human Rights, with the aim of speeding up the process of collecting testimonies and making these more widely visible.

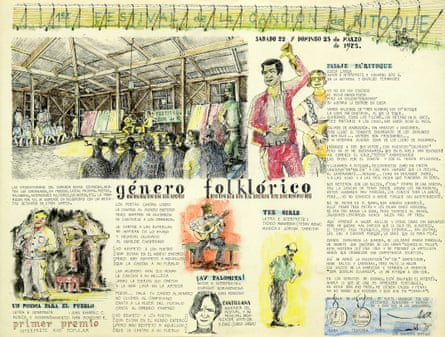

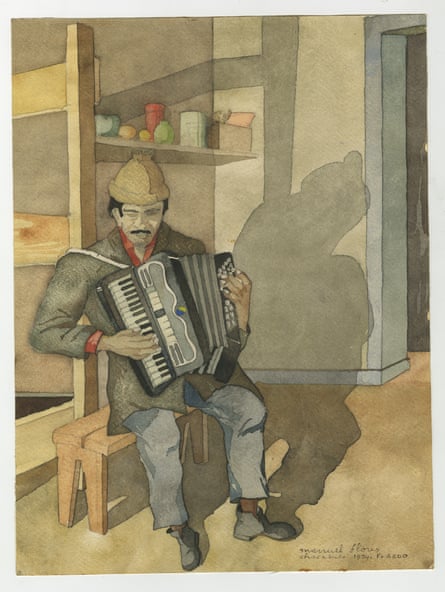

About a third of the songs she has found were partially or fully written by those in captivity. “Some people became musicians or songwriters while detained,” she says, “and the originality of these songs is one of the valuable things about the archive.” On some occasions, Chornik collected recordings never heard before that were made in captivity and either smuggled out or hidden. One of them, Oratorio de Navidad segun San Lucas (Christmas Oratorio According to St Luke), was written by the famous songwriter Angel Parra, who survived the Chacabuco concentration camp. The song seems to demand of a listener to close their eyes and conjure the scene.

One of the singers in Angel Parra’s band was Marcelo Concha Bascuñán, who disappeared in 1976 and was never seen again. Chornik collected a recording of his voice while imprisoned in Chacabuco. “After I collected the tape,” says Chornik, “and his family heard it, they said it was the closest they’ve ever felt to having Marcelo alive.” The heartbreaking speech thanks Parra and explains: “These songs are … a reflection of love towards the people who are waiting for us, and, in general, to all of those who have shown their solidarity, their concern and their support towards everyone who is in our situation. It is, therefore, a manifestation of hope, of trust, of faith, in sum: of love for life – which is love for freedom.”

There is no overstating the horror in Pinochet’s jails, prison camps and detention centres. Serial human rights groups – international and Chilean – have documented the litany of torture, maltreatment, starvation, beating and sexual abuse of some 40,000 people, with 2,250 more executed and 1,300 “disappeared”. But this is not Chornik’s remit – she seeks to record for history the strange story of how those subjected to this brutality responded by singing and playing, or listening to, music.

“It was a cultural activity, but also a social one. There are many accounts of people singing between sections: men to women, women to men – they’d sing to one another, like a dialogue. And singing as a way of establishing presence to people outside the prison walls.” One witness, Beatriz Bałaszew Contreras, says that after she was interned in the notorious Tres Álamos prison camp in Santiago: “I met someone who lived a block away from Tres Álamos and said that she could hear us.”

On most occasions, Chornik records a prisoner’s memories and finds a performance – or arranges one – of an approximate version sung or played in detention. In the case of, for instance, the Andean folk tune Doctorcitos (Little Doctors), as sung in the Chacabuco concentration camp, she records testimony from prisoner Luis Cifuentes, and posts a recent recording of the song by a group of ex-prisoners that was formed specially for the occasion, Macomba, in homage to Marcelo Concha Bascuñán.

The song cocks a clandestine, coded snook at the captors: “Little Doctors”, says Cifuentes, was a derogatory term for government officials.

A song called Let’s Break the Morning is recalled by María Soledad Ruiz, who used to visit her father at a camp on Isla Dawson, a terrifying picture of which accompanies the song’s lyrics.

One of the original recordings in the archive (though this time not collected by Chornik) is of a song called El Suertúo (Lucky Devil), which presents an ironic chronicle of life in detention.

One recording is of a song by the most prolific composer in the archive, Sergio Vesely, sung at shows laid on by prisoners to entertain their children on family visiting days at Melinka prison camp; the commander and his guards would sit in. It is a light-hearted song, about a King Ñaca Ñaca, but pokes fun at the commander and indirectly Pinochet himself: “At the end Ñaca Ñaca loses his voice – that is, his power – and he loses his mind,” says Vesely. “Thus the captives become free. The play’s language was so poetic that the commander, seated as always in the front row, did not get it. If he had understood, we surely would have been punished.”

Exactly the same trick was played in the Terezin concentration camp, at which the Nazis tolerated music, in an opera called The Kaiser of Atlantis, composed by the prisoner Viktor Ullman. The Kaiser was a parody of Hitler.

Much music comes from the infamously murderous Cuatro Álamos camp – from which comes a searing testimony, by Luis Alfredo Muñoz González: “One night, between the guards’ shouts and bustling, all the prisoners were taken away from Cuatro Álamos … Very early the next morning, I was awakened by the voice of a woman calling my name. Still drowsy, I thought it was Diana calling me from some place in the ‘hereafter’. The voice cautiously persisted.

“The voice came from the right of my cell. Naked, I went to the window (I showered dressed so as to wash the blood from my clothing, which I then hung to dry from the bars of the window).

“‘Who are you?’ I asked. ‘They’ve taken everyone away. They told me they were going to kill those of us still here,’ she said. ‘Who are you?’ I asked. ‘They call me La Jovencita [Young Girl]. I am from Argentina and they nabbed me in Valparaíso. Do you think they will kill me?’

“‘No, they won’t kill you,” I told her. ‘That will be me, not you’ … After a long silence, La Jovencita said: ‘I feel very sad and very alone. Would you sing to me … that song you sang the other night, the one about the doves?’ My voice rose … as if it had a will of its own.”

“Both sides recognised the power of music,” says Chornik, and sometimes music was, she says, “imposed on the prisoners”. Inmates were subjected to “loud music as an accompaniment to interrogation and as a loud intimidatory sound”. In other places, inmates were “made to listen to and even sing the national anthem, to which the junta had reinstated an old stanza glorifying the military.”

La Discothèque – ironically known as La Venda Sexy, the Sexy Blindfold – was a house at Calle Iran 3037 in Santiago in which scores of leftists and others were kept and tortured.

There are no testimonies yet of music having been sung at the house, but Beatriz Bałaszew Contreras, also interned there before Tres Álamos, recalls incessant music played “very loud” to “pressure you to collaborate”.

Bałaszew Contreras recalls a means of survival whereby “I manufacture the silence: I close the door, I shut myself in … the noise was loud but I was doing my own thing.” Then she recalls: “The only thing that would change the noise to music for me was this song [Today I sing just for the sake of singing]. I have no idea how many times I listened to it. For me it was reiterative.”

According to an ex-member of the Dina secret police Chornik interviewed, the names La Discothèque and La Venda Sexy were coined by the agents themselves. “Venda” comes from the blindfold that prisoners had to wear at all times; “sexy” comes from the high level of sexual violence perpetrated by Dina agents, especially against women. (At present, a family lives in La Discothèque. Survivors have campaigned for the state to buy the house and turn it into a museum, but the owners have not agreed to sell it.)

To Chornik, the especial significance of La Discothèque is that her parents were there. “I experienced Chile in a fragmented way,” she says of her homeland. “My parents were exiled and moved back at the end of the dictatorship [in 1988]. I came to England a few weeks before Pinochet was arrested, and returned to Chile two days before he died. Our lives are mingled.”

She adds: “I started this work with La Discothèque. I was a child when I learned that my parents had been in it, and I have quite vivid memories of them meeting together with other ex-prisoners who had been there, and going to find the house after the dictatorship ended. But I was well protected; my parents told me a little, but not the details.

“So it was a revelation. The penny dropped. Against my parents’ wishes, I went to La Discothèque for a first time. And because I am a musician, I was touching some sensitive fibres: the idea that this place was called ‘The Discotheque’ opened a rainbow of questions. I put them aside for many years…”

But in the early 2000s, Chornik was studying at the Royal Academy of Music, and a number of circumstances converged, some of them between her DNA and her work: “All my paternal antecedents were refugees, Jewish from the 1906 pogroms, and my paternal grandmother was a violinist in an all-women’s orchestra, Orquesta de Las Señoritas.”

Chornik began to research Alma Rosé, niece of Gustav Mahler who, from the violin, directed an orchestra in Auschwitz-Birkenau to stay alive, though she perished from disease. “Then,” says Chornik, “I switched my idea into a comparative study between music in the Nazi camps, and in the Chilean camps.

“I was aware that I was working out my parents’ life, except through the experiences of people who went through similar things. It was a way to learn about them sideways. As the project expanded its horizons, I realised that in Chile’s case, I had some kind of role – I needed to explore this, to record these testimonies for future generations, for many of these people are elderly now.”

Why music, in those conditions? “Music is the most emotional of the arts,” says Chornik, “and it’s an emotional response. You do not need tools or props – it’s human to sing, and an assertion of your humanity in an inhumane place.

“The stress was so high, the uncertainty was so high – and this was a way of reducing that stressful uncertainty. They sang as individuals, in groups, and as a community of people, which was the most important thing, perhaps.

“There were 40,000 prisoners in 1,132 places of detention, and we have 130 testimonies,” she says. And each person will have a different memory. Some people will tell you stories about music in a place that someone else will swear there was none.”

The songs are political when they could be, but not often – they include love songs, songs about home and nature. “Whatever was in fashion at the time,” says Chornik. “It’s not logical, why should it be?”

- This article was amended on 4 January 2017 to correct the location of the Tres

Álamos prison camp.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion