Airbnb, the startup that has fought tooth and nail to avoid regulation in cities around the world, appears to have reversed its attitude toward regulators in a dramatic change of policy.

In a deal with London and Amsterdam announced this week, the company has agreed to take on the responsibility of policing limits on the number of days per year a full unit can be let through its system, making it the first short-term rental company to cut such a deal.

Some analysts have met the move with cautious optimism, hoping that the short-term rental giant might finally be able to get its regulation problem under control before its mooted IPO.

Under the deal, Airbnb will be responsible for making sure their hosts stick to the local limits for short-term rentals unless the hosts have the proper licenses – 90 days per year in London, 60 per year in Amsterdam.

Even more so than Uber, Airbnb has struggled against local regulatory environments as it grew. It has been engaged in protracted battles with city authorities in San Francisco, New York, Berlin, Barcelona, and scores of other cities – often because it is blamed for eating into the housing stock – and falls into legal grey areas in places like Japan. In Iceland’s capital, Reykjavik, critics say Airbnb is to blame for a total drying-out of the long-term rental market.

In Australia, where a construction boom means cities worry less about draining housing stock, regulatory bodies have been more open to short-term rentals, according to Julian Ledger, the CEO of the Youth Hostel Association of Australia.

But even there, the company is controversial. The state government of New South Wales is preparing a response to a parliamentary enquiry into Airbnb earlier this year. Public opinion, Ledger said, was “mixed”.

Dutch MP Mei Li Vos, a supporter of regulation of the “sharing economy” in Holland, welcomed the Amsterdam deal. “I think it’s a good step forward,” she said. “Some very stubborn people and hosts of illegal hotels will persist, but it’s a good thing that Airbnb finally listens to the complaints of its neighbors.

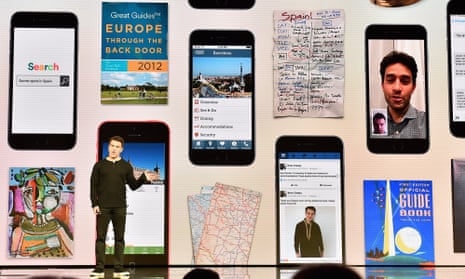

“It’s a positive development for Airbnb, because the more certainty there is around the structure for Airbnb in cities around the world, and the less uncertainty there is about what is legal and what isn’t, [the better],” said Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business who studies the sharing economy.

Sundararajan found the move especially heartening in the face of Airbnb’s $30bn valuation and possible future IPO - though others have suggested that the move was a kind of Potemkin village move designed to reassure skittish investors before a possible offering.

Not all of Airbnb’s supporters were overjoyed. Andrew Moylan, the executive director of the R Street Institute, a libertarian thinktank, was concerned by the precedent that was set by the deal.

“Airbnb and other short-term rental services have been fighting these existential battles across the world, and this is worrisome to me in that it’s the first time I’ve seen a company make a concession of this scale in basically agreeing to serve as an extension of law and code enforcement on behalf of the cities in which they have to operate,” he said.

Opponents of the company, however, expressed skepticism that Airbnb could be trusted to self-police. “It’s a little bit like having the fox watch the chicken coop,” said Joe LaCava, a community leader and former chairman of the San Diego Community Planners Committee.

Judith Roth Goldman, the co-founder of Keep Neighbourhoods First, a Los Angeles-based grassroots coalition opposing Airbnb-type rentals, said that Airbnb would “do anything to keep their $30bn IPO valuation”.

“Let’s see if Airbnb follows through as agreed,” Goldman said. “Only time will tell, but truthfully I can say that we’re hopefully optimistic that they’re committed to comply – but we’re skeptical given their track record.”

Dale Carlson, the co-founder of Share Better San Francisco, a pressure group agitating for greater regulation of Airbnb, said that the move was a good thing “only if it’s real,” but felt that his experience of the company led him to doubt that they would follow through with the deal in good faith.

“Don’t buy the Airbn-BS” was his advice to London and Amsterdam. “These guys are really quite shameless.”

- This article has been amended to state that Keep Neighbourhoods First is based in LosAngeles, not New York