'cen.sor': The hidden beauty

Over the years, the image of women in Indonesia has constantly been under scrutiny, diminishing their significant roles and contributions in the process.

Change Size

Silent is Golden, 2016, by Ari Bayuaji (Instragram/Ari Bayuaji)

Silent is Golden, 2016, by Ari Bayuaji (Instragram/Ari Bayuaji)

T

he faces on the busts of Queen Ken Dedes placed in several corners of RedBase Foundation’s exhibition hall in Bantul, Yogyakarta are far from depicting the renowned image of her perfect beauty — they are splashed in pink, carved out, or painted over with a cross sign.

The statues are among 34 works, including paintings and art installations, created by visual artist Ari Bayuaji following his artist-in-residency program at the foundation.

In the exhibition, entitled “cen.sor”, he explores how women’s images have been represented in Indonesia over the years while, at the same time, underlining how society’s structural censorship has essentially diminished women’s power.

For his solo exhibition, which runs until Dec. 6, Ari, who resides in Montreal, Canada, dug deep into his Javanese roots, working with the memory of his mother in mind. His late mother worked hard all her life, something he indirectly connected to when he saw how women dominate economic sectors in Yogyakarta’s many corners, from rice fields, traditional markets to food stalls. “Women are not just dealing with house chores, but also become the family’s economic backbone. You only have to see these markets and rice fields to see how important women are,” he said. Some of the works he created for the exhibition were inspired by what his mother did to the Balinese statues in her collection in the past. Two years ago, after her return from haj, Ari’s mother was advised by several family members to get rid of the statues — most of them were of Balinese women who were naked above the waist — as they considered them “improper” for her to have after her pilgrimage. His mother, he said, did not get rid of the statues she had collected for many years, but finally decided to compromise – censoring parts of the statues that were considered “improper” with batik fabric.

“I think what my mother did was funny but smart at the same time. She tried to negotiate with ‘social pressure’ that she could not fight against because of her religious belief,” Ari said. After her return from haj, his mother also received much advice about wearing a headscarf and she complied, even when she was teaching aerobics. “And then again, she compromised between her obligation to wear a headscarf and her work by designing her own clothing and headscarves so she could still be stylish.”

(Read also: Six Muslim fashion wear designers to adore)

Before arriving in Yogyakarta for the artist-in-residency program, Ari equipped himself with his mother’s handwritten notes on aerobics and pictures of her from different years.

He later intermixed these files with abundant materials he found in Yogyakarta, where he also gathered up samples of Indonesian women’s images from ads and photos from old magazines, old stamps and products used by women in the past.

He later manipulated these images by covering or cutting them or adding other materials to them in a way to suggest censorship.

His works showcase significant changes in Indonesian women’s images, especially on Java, over the years.

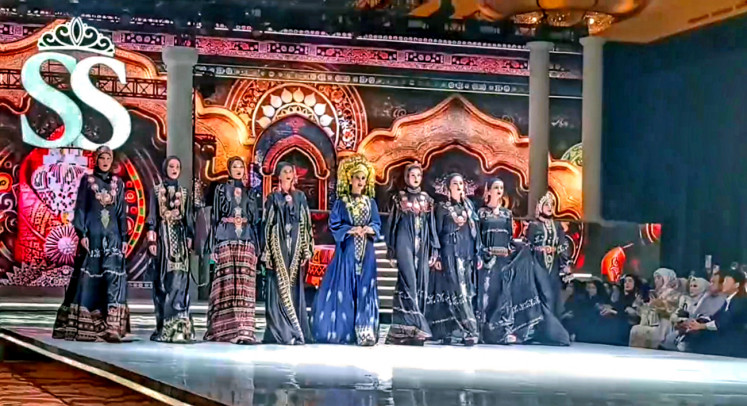

Decades ago, the image of women wearing kebaya, Indonesia’s signature fashion heritage, and sanggul (elegant chignon) was a symbol of great beauty. These days, the elegant style have been replaced with fashionable Muslim wear and hijab in various colors and styles.

The artist also placed a collage comprising handwritten files and two pictures of his mother, Sutianingrah. One was of her wearing a gym outfit and the other one had her still in a gym outfit, but with a hijab.

He considered the transformation as one example of Indonesian women’s spiritual phase. “I’m not saying I agree or not with my mother wearing a headscarf, but this reflects a process that happens around us […],” he said.

The artist also created another collage comprising old ads of a shampoo product that in the past showed a woman in sanggul, while next to it, the product’s latest ads display women in headscarves.

Ari said the collage was inspired by a “Delete Sanggul” campaign by several university students during a car free day event in Surakarta, Central Java, several years ago.

“This reality makes me sad. It’s not that I disagree with those wearing headscarves but we, as Indonesians, have an identity with roots dated from hundreds of years old that needs to be preserved as well,” he said.

(Read also: Censorship humiliates women, says activist)

Ari saw a shift of values on beauty, morality and propriety within society that depend on social and political circumstances at specified times, restrictions that often become morality benchmarks set by certain customs or religions. “I can directly see this in censorship conducted by several television stations in Indonesia. The censorship is imposed on women’s clothing — either on humans, female cartoon characters, or even female robots in kids’ films,” he said. The reality made him wonder how, in a modern time like today, women’s clothing is still a big issue and is being used as a reason to discriminate against them.

Women’s clothing, he said, becomes a “moral propriety” for women, like the move to censor kebaya by some of Indonesia’s television stations.

“Many did not realize these issues blur the real and much more important matters like the crucial roles of women in education and children’s health, as well as women’s big role in our economy,” Ari said.

“Discussion of the right clothing for women is a ‘censorship’ of women’s powerful roles that are much more important.”

Such thoughts, he said, influenced his creative process during the artistin-residency program. “I intentionally create three dimensional objects that are a bit abstract to give space for people to think, question, or imagine the meaning of ‘censorship’ in these works,” he said.

Art observer Farah Wardani said in the exhibition’s introduction that Ari may have explored women’s images but the artist was fully aware that the image of women within society has changed over time.

The artist, she said, never felt the changes to be problematic, nor to be necessarily ‘’right’’ or ‘’wrong’’ choices.

“In his art, he just wants to show how the value attached to different images is subjective and, by playing around with them, to underline the paradoxes and ambiguities of these images,” Farah said.

“It may also be that this project, like many of Ari’s works, is an attempt to promote freedom from censorship and its negative consequences, freedom of an individual to gain strength and to enjoy liberty, in harmony with the rest of society.”