To see how much Formula One has changed, you could go back 60 years, to the finale of the 1956 season, when a 24-year-old Englishman voluntarily gave up his chance of the world championship to an Argentinian rival old enough to be his father. It was a race in which the two early leaders fought each other so hard that they both had to come in for new tyres after only four laps, and in which the eventual winner, having run out of petrol with a handful of laps to go, was shunted a mile or so back to the pits for a quick fill-up by a fellow competitor who happened to be driving the same make of car.

Today’s F1 fans, watching Lewis Hamilton and Nico Rosberg regularly treating each other with glacial disdain before mounting the podium, might find it hard to believe that such a universe ever existed – one in which drivers fought every bit as fiercely but behaved on and off the track as if they respected and even liked each other. Nowadays we have Sebastian Vettel, a four-time world champion, and Max Verstappen, a 19-year-old future champion, settling their petty on-track differences by exchanging text messages, as they did after the race at Interlagos a fortnight ago.

Christian Horner, the boss of the Red Bull team, mischievously suggested this week that were the two Mercedes drivers to start, as usual, from the front row in Abu Dhabi on Sunday, and were Hamilton to take an early lead, the Englishman might choose to slow up and back his team-mate into the pursuing pack, thus putting the championship leader into the sort of difficulties that could cost him the points he needs to secure the title.

Although Hamilton immediately dismissed the notion, the fact that the idea could even be voiced shows how far the moral compass of Formula One has swung. Of course, Horner might say that he was merely reacting to the equally gratuitous and even improper suggestion a fortnight earlier from Toto Wolff, his opposite number at Mercedes, that the two Red Bull drivers should leave the Mercedes pair to race for the title without hindrance.

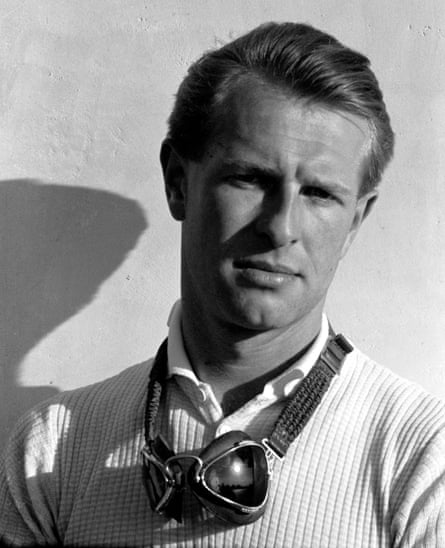

Sixty years ago, on a warm but overcast day at Monza, Peter Collins, the almost unfeasibly handsome blond-haired son of a Kidderminster garage owner, went into the eighth and final round of the series as one of three drivers still in with a chance of taking the championship. His Ferrari team-mate Juan Manuel Fangio, already three times champion, led the standings with 30 points. Collins and Jean Behra, the No2 to Stirling Moss in the Maserati team, had 22 apiece.

In those days the points per race went from eight for a win down to one for sixth place, with an extra point for setting the fastest lap. To take the title, the Englishman and the Frenchman needed to win the race and record the fastest lap, with Fangio completely out of the points. Back then, too, drivers were allowed to share a car and divide the points, as Fangio had done in the opening round in Argentina, when he won the race after taking over the Ferrari of his team-mate, Luigi Musso, when his own fuel pump failed. He had taken Collins’s car after crashing at Monaco, where they finished second. This was motor racing’s equivalent of the droit de seigneur, a team leader’s prerogative, and it was eventually outlawed.

As the grid formed up in front of the Monza grandstand, with the dampness from a morning shower still drying on the track, Fangio had won two and a half grands prix that season, to Collins’s two. Moss, with one win and a total of 19 points, was just out of contention. The grid consisted of five Ferraris, 10 Maseratis and three cars each from Vanwall, Connaught and Gordini.

Two of Ferrari’s young Italian tearaways, Musso and Eugenio Castellotti, roared away at the start, each hoping to win his home race, only to run into trouble caused by the inability of their tyres to handle the rough surface of the track’s high-speed banked section. Musso fought his way back to second place but was doing 160mph on the banking when he suffered Ferrari’s third steering failure of the weekend, returning to pits shaken and in tears.

When Fangio’s steering had broken at a safer speed earlier in the race, Musso had sat tight and refused point-blank to give up his car. Collins, however, graciously let the maestro take over his cockpit with 15 of the 50 laps to go, handing Fangio a share of second place and the three points that secured a fourth title.

Afterwards Collins said to a friend, the photographer Bernard Cahier: “It’s too early for me to become world champion – I’m too young. I want to go on enjoying life and racing, but if I became world champion now I would have all the obligations that come with it. And Fangio deserves it, anyway.” He told the Daily Mail: “I think Fangio is the best driver in the world, and a charming man, too.”

Although the Italian newspaper Momento-sera praised his “nobility, style, class and sporting dignity”, not everyone joined the applause. The Sunday Express vented its harrumphing disapproval of what it saw as a “quixotic gesture” that had potentially deprived Britain of its first world champion. Two years later Collins might well have gone on to achieve that distinction had he not been killed in the German Grand Prix; instead it would go to Mike Hawthorn, his team-mate and best friend.

A fortnight before his death he had looked well set when driving his Ferrari to victory in the British Grand Prix at Silverstone. The trophy presented to him that day, an elegant silver-plated cup 18 inches tall, goes under the hammer at Bonhams next month, the auctioneers’ estimate of around £5,000 hardly reflecting its significance as a reminder of the values of a different time.