Schiaparelli: Esa gives update on Mars crash investigation

- Published

The European Space Agency has released details from its preliminary report into the Schiaparelli crash on Mars.

The investigation confirms the probe misinterpreted sensor data, which made it think it was below ground level, when in reality the module was still at an altitude of around 3.7km.

This prompted Schiaparelli to jettison its parachute too early and to fire its landing rockets for just three seconds.

These actions put the probe into a freefall that led to its destruction.

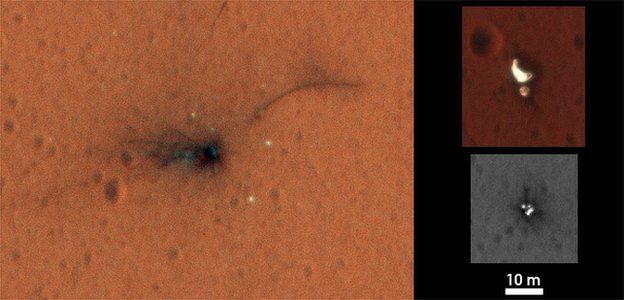

A crater and scattered hardware were later imaged by an American satellite.

"This is still a very preliminary conclusion of our technical investigations," said David Parker, Esa’s director of human spaceflight and robotic exploration.

"The full picture will be provided in early 2017 by the future report of an external independent inquiry board, which is now being set up, as requested by Esa’s director general, under the chairmanship of Esa's inspector general.

"But we will have learned much from Schiaparelli that will directly contribute to the second ExoMars mission being developed with our international partners for launch in 2020."

Schiaparelli was part of Esa's ExoMars programme - a joint venture with the Russians - which is endeavouring to search for evidence of past or present life on the Red Planet.

The 600kg robot was conceived as a technology demonstrator - a project to give Europe the learning experience and the confidence to go ahead with the landing on Mars in 2021 of an ambitious six-wheeled rover.

This future vehicle will use some of the same technology as Schiaparelli, including its doppler radar to sense the speed and distance to the surface on descent, and its guidance, navigation and control (GNC) algorithms.

Schiaparelli's landing sequence - stage by stage

Engineers will be encouraged that so many key systems on the descent probe worked as expected on 19 October.

The parachute deployed as planned at an altitude of 12km when the probe was travelling at a speed of 1,730km/h.

The vehicle's heatshield, too, did its job of slowing the probe and protecting it from the high temperatures of atmospheric entry - and this disc-shaped shield was released at an altitude of 7.8km.

But it was then that the descent sequence started to go awry.

Schiaparelli's inertial measurement unit (IMU) had earlier sensed rotational accelerations in the probe when the parachute first opened that very briefly stepped outside what had been anticipated. The data became "saturated".

Unfortunately, when this information was then taken in by the GNC system, the probe incorrectly updated where it thought it was in the descent. And when the data from the doppler radar subsequently kicked in, the error already in play was propagated forward.

At one stage, Schiaparelli even calculated its position to be several metres below the surface of the planet.

"The system ended up calculating a negative altitude," explained Esa's Schiaparelli's manager, Thierry Blancquaert.

"And this is when the probe initiated the other steps - which was to release the parachute attached to the backshell, switch on the propulsion system, and then switch it off, and then switch to surface mode."

As it went into freefall, and thinking it had already touched down, Schiaparelli started up its post-landing sequence, including booting up its onboard weather station and getting ready to transmit the pictures it had been taking on the way down.

The probe crashed into the dusty, equatorial Meridiani Plain at a velocity of about 150m/s (540km/h).

All this information was discerned from telemetry that Schiaparelli sent back as it hurtled down through the Martian atmosphere.

Engineers will take the lessons learned into the 2021 landing, assuming the rover mission is approved.

"Because we know what went wrong, we can correct it; and I'm super-happy to have reached this conclusion," Thierry Blancquaert told BBC News.

Europe's research ministers still have to find the funds to carry the rover project through to completion. This matter should be resolved at the Esa Ministerial Council in Lucerne, Switzerland, on 1/2 December.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

- Published7 November 2016

- Published27 October 2016

- Published21 October 2016

- Published20 October 2016

- Published20 October 2016