OPINION:

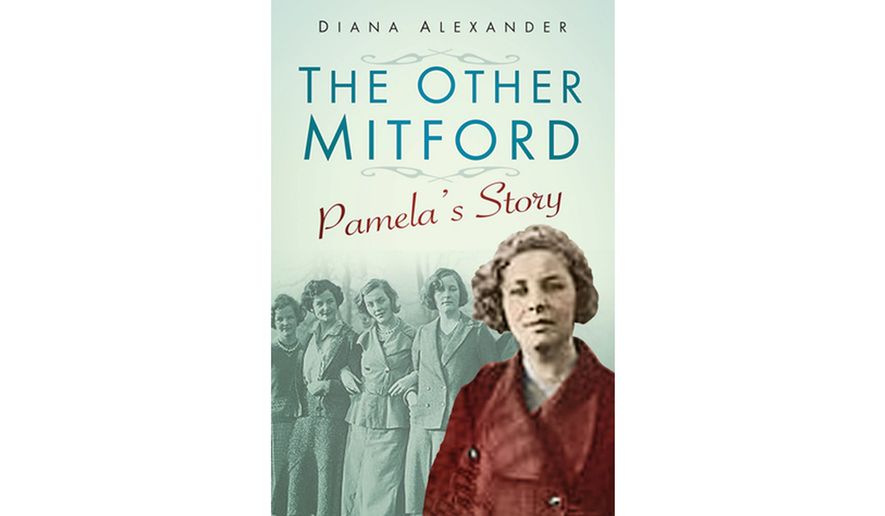

THE OTHER MITFORD: PAMELA’S STORY

By Diana Alexander

The History Press/IPG, $17.95, 192 pages, illustrated

The eponymous Mitford who is the subject of this hybrid memoir/autobiography is an unusual sort of odd woman out in a group of six sisters, but in this family, being the ordinary or regular one, makes her stand out. Her nickname Woman connotes her cozy, domestic qualities, general air of benevolence and serene beauty, a cuckoo in a nest of vipers.

For she was not Unity, who went to live in Nazi Germany, became Hitler’s archetype of the Nordic female ideal, his close confidante at the very least, such a fanatic Nazi that she shot herself in the head in a failed suicide attempt when war broke out in 1939. Or Diana who married Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists, in the beaming presence of the fuehrer at the Berlin home of Josef and Magda Goebbels and was interned with him by her cousin Winston Churchill for several years during World War II. Or Jessica, who became a diehard Communist, but nonetheless emigrated to the United States where she became a party activist in California who refused to take a loyalty oath, and made pots of money as a muckraking journalist and author.

Nor was Woman at all like her elder sister, sharp tongued Nancy with her acid-dipped novelist’s pen, whose merciless teasing of the first sibling to rival her privileged position as only apple of her parents’ eye, is credited by Pamela herself and the author of this book, who knew her well as neighbor and friend, with giving her a much-needed thick skin. And even the sister seemingly most like her in temperament, the youngest one Deborah, had a preternatural ability to achieve her goal somehow, no matter the obstacle. Determined to be a duchess from her earliest years, she married the younger son of the Duke of Devonshire, only to find herself married to the heir when his older brother (childlessly married to President Kennedy’s sister) was killed in action shortly after D-Day and only a few years later a real-live duchess. There is something unnervingly witchlike about her ability to get what she most desired and her certainty about attaining the rank she felt was her due.

So yes, compared with those five sisters, Pamela was the ordinary one, a domestic goddess sublimely oblivious to much, if not all, of the turmoil they were engendering inside the family circle and beyond. Reputed by her siblings to remember every meal she had ever eaten to the end of her long life, she is forever being mentioned in memoirs popping up on both sides of the Atlantic with her signature roast chicken, her quintessential comfort food, pouring oil on troubled waters. As Pam’s neighbor in the cozy English village where she spent her later years, Diana Alexander provides ample testimony to her inspired cooking and also her gift for original additions to the most humble of dishes.

But just because you’re the regular one among that lot doesn’t make you really ordinary. Indeed, with her myriad oddities, high-pitched laughter, and peculiar behavior, she would seem eccentric in most milieus. Her obtuseness in itself is extraordinary. Taken to lunch with Hitler by Unity, she did not, as did most who encountered him, find him mesmerizing, whether admiringly or with horror, “describing him on her return to England, ‘as very ordinary, like an old farmer in his brown suit.’ Nevertheless, she remembered the meal she had eaten in every detail, especially the delicious new potatoes.” Food over fuehrer — talk about the “banality of evil.”

Even the exemplary female qualities that engendered her nickname are somewhat undercut by her belated, unsuccessful childless marriage after being jilted once and turning down many proposals from besotted suitors: also her discomfort with babies and young children. Said by most who knew her to be apolitical, she and her husband were nonetheless adherents to the British fascist movement, opposed going to war with Hitler, took the traitorous Mosleys into their home after they were finally released from prison, and were uncritical of Unity. You can ascribe this to familial solidarity, but this family is so deeply rooted in creepiness, almost genetically as pointed out by David Pryce-Jones in his groundbreaking study of Unity (which Pamela abhorred), that I could not help sensing something unsavory beneath that thick-skinned, placid exterior.

• Martin Rubin is a writer and critic in Pasadena, Calif.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.