No one is ever going to accuse reigning PDC world darts champion Gary Anderson of hyping up the film he’s more or less the hero of. “It’s not as bad as I thought it would be,” he says, when asked what he thinks of House of Flying Arrows, a documentary that follows his progress through the 2016 world championships. “I mean, I never watch myself play darts or anything. So, you know, it was bit strange to sit there, actually watching myself for a change. To sit and listen to myself talk. My God, no … ”

The voice of the man who the late Jocky Wilson nicknamed The Flying Scotsman trails off. Then he brightens. “But I quite enjoyed it. It turned out all right.” It certainly did. On the face of it, darts seems a fairly improbable subject for a feature-length documentary. This is, after all, a sport in which, as co-director Daniel Mendelle admits, “People essentially stand in the same position repeating the same action over and over again.”

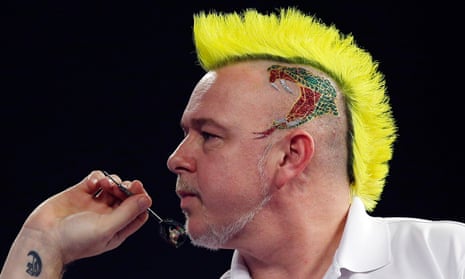

It’s also a sport in which extravagant showmen (such as world No 5 Peter Wright, who has a large snake painted on the shaved sides of his head in tribute to his love of lethal tipple snakebite) are vastly outnumbered by self-effacing everymen like Anderson who, as he puts it, “class ourselves as ordinary working-class people who just play darts”.

And yet House of Flying Arrows is a fascinating film. Quite aside from the stuff you might expect to see in a documentary about darts (Eric Bristow reminiscing about the old days, footage of Bobby George in his youth, when the self-styled King of Bling looked both like a surrogate member of the Clash and, as a female friend of mine noted, “as hot as the Earth’s core”), its 90 minutes variously deal with psychology, neurology, class and mathematics.

In one brilliant sequence, it shifts from an interview with a former Countdown champion who now uses his skills as a darts referee, via an academic explaining the intricacies of mental arithmetic, to some frankly jaw-dropping film of former player and latterday commentator Wayne Mardle reeling off the maths behind different finishes at incredible speed.

“One of the things we hope we’re doing is changing the way people look at darts,” says the film’s other co-director, Guardian sports writer Daniel Harris. “Not just in a classist way, although there is, for sure, a lot of class snobbery about darts. We’re just trying to present darts in a different way, saying, ‘What haven’t people seen before? What haven’t they thought about before?’”

In addition, it has the gripping air of a documentary whose storyline quickly ran out of its makers’ control. At the outset, the directors clearly expected the 2016 championships to play out as a battle between reigning champ Anderson and world No 1 Michael van Gerwen, who present an intriguing study in contrasts. The former is shy, haunted by a period during which the deaths of his father and brother caused him to start missing doubles, and so crippled by nerves that he vomits before games. The latter is an ebullient, charismatic Dutch skinhead with what Harris calls “an amazing face for cinema”, who claims he never actually aims his darts and seldom misses an opportunity to inform the world of his nonpareil genius.

But it didn’t work out like that. Shortly after telling the cameras that his current form represents “the greatest darts ever seen on television” (albeit not without reason: in July this year, he scored the highest average ever recorded in a televised match), Van Gerwen is knocked out in the third round. “He throws his darts like a flaming javelin,” says Harris. “That average he got in July, it’s hard to believe a human being can get much better at darts than that. You’d probably struggle to construct a robot that could do better. But I think his opponent just handled the pressure better. One of the things that’s fascinating about darts is the pressure, and how players cope with it, which is why we’ve got a neuroscientist who specialises in pressure explaining what’s actually going on.”

As the finals progress, you find yourself increasingly rooting for Anderson despite, or perhaps because of, his often visible discomfort at being filmed. Indeed, there’s a sense that the film might reach its climax not with the final itself, but just before, when Anderson finally tires of the crew’s presence: about to walk on stage, he looks directly into a camera, smiles, and quietly but firmly tells them to fuck off.

Meanwhile, a raft of other players are introduced, almost all of them fascinating in their own way, but none more so than the drily funny, very eloquent James Wade: a man diagnosed with ADHD, bipolar disorder and autism, who used to have Dizzee Rascal’s Bonkers as his walk-on music. It explores their peculiar brand of fame: on the one hand, there’s big money to be made as a professional, as you might expect, given that the Premier League tournament can fill out every arena in Britain, from the London O2 to the Glasgow Hydro; on the other, even the biggest stars will turn up at exhibition matches and play local players and members of the audience, the equivalent of Jamie Vardy or Cesc Fabregas arriving at a provincial Sunday league pitch for a kickabout.

Then there’s the curious relationship between darts fans and their sport. It starts, says Harris, from an unusual premise: “If you go to watch darts, you can’t actually see the action. You can’t really see the dartboard unless you watch it on the screens, so people go along to have a party. People dress up in fancy dress. One guy we met while filming at the championships started explaining that by talking about Guy Debord and The Society of the Spectacle.”

Harris frowns at the mention of the French Marxist theorist and his influential work. “I think we disagreed about that a little. I think it’s more like a fancy dress party. They behave differently to the way they normally would because they’re drinking and they’re in fancy dress. But it’s all in a really non-threatening way: it’s not partisan, there’s none of the needle you get in football. People might have their favourites, but everyone cheers everyone. I don’t want to sound soppy, but it’s quite a beautiful thing to see.”

Harris always thought a big-screen documentary about darts would work. “Obviously, it doesn’t have the aesthetic beauty of boxing or tennis or football or cricket, but it’s just got a special kind of drama. No other sport shows simultaneous action and reaction. No other sport deals in such close-up images. That gives the human story a unique intensity. One of the things about sport is that you’re basically voyeuristically watching someone live out the most exhilarating, demoralising moments of their life – and nothing gives you that with the same level of intensity as darts. There’s no luck or tactics involved, there’s nothing players can do to affect one another, and if you’re in trouble, no team-mate can save you. You can’t roll, cover up, or block a few. It’s a simple game, but there’s an incredible amount going on.”

Although Gary Anderson didn’t always enjoy being filmed away from the oche (“There’s days when you get home and you just want a bit of peace and you’ve got a wally with a camera there”), he does agree that the film has captured something of the game: “It shows people what we’re like. I mean, I keep saying, we’re no superstars, we’re just darts players. But,” he adds, “I thought it was quite good.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion