- India

- International

Dear Peromboke Man: Letters from Mahasweta Devi to ‘Anand’ P Sachidanandan

She was the iconic activist-writer of Bengal. He is the most important living novelist and essayist in Malayalam. Letters from Mahasweta Devi to Anand, written between 1996 and 1998, reveal a rare friendship, forged by a love of literature and a concern for justice.

Yours truly: Mahasweta Devi and Anand, a photograph from the latter’s album. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Yours truly: Mahasweta Devi and Anand, a photograph from the latter’s album. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

They met the first time in 1996 as members of an Indian writers’ delegation to Dhaka. She was already the iconic activist-writer, whose fame had crossed the boundaries of the language she wrote in. He, though considered the most important writer of his generation and feted as such in his state, was little known outside his language. But Mahasweta Devi took an instant liking to Anand, the nom de plume of P Sachidanandan, arguably the most important novelist and essayist in Malayalam since OV Vijayan.

There could not have been two different personalities — if Mahasweta Devi was the exuberant one, always making herself heard and leading the way, Anand, 10 years younger, is the quiet, reticent writer, unwilling to be in the spotlight and preferring the written word to embody his presence. However, the question of justice was at the core of everything they both wrote.

Mahasweta’s popular works like Aranyer Adhikar (The Right of the Forest), Hajar Churashir Maa (Mother of 1084), Jhansir Rani (Rani of Jhansi) and numerous short stories were about the oppressed and the unrepresented, and a call to remake the worlds we live in. Anand’s major novels such as Aalkoottam (Crowd), Marubhoomikal Unadakunnathu (Desert Shadows), Govardhante Yathrakal (Govardhan’s Travels) and his many essays analyse the present against the backdrop of history, raising disturbing questions about people and politics in the process. People forced to live on the margins of society — the peromboke people, as Anand would describe them in Desert Shadows — interested and disturbed both writers. The concern for the peromboke people forged their friendship.

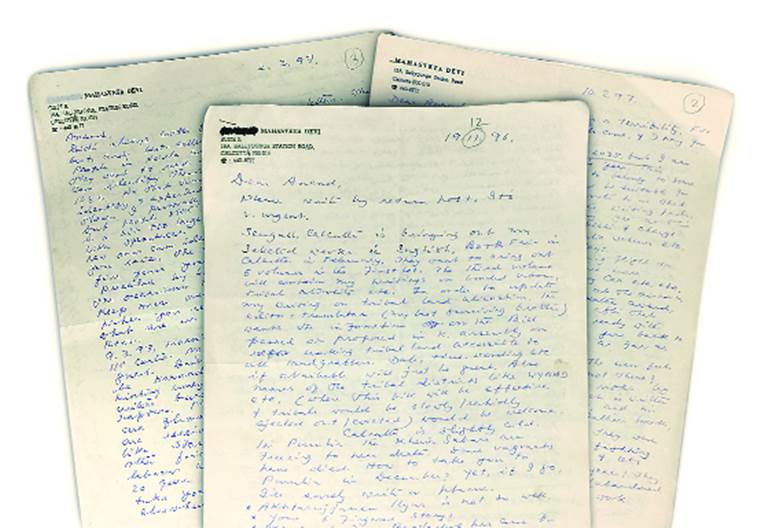

She wrote him long letters, on her letterhead — Mahasveta Devi, 18A, Ballygunge Station Road, Calcutta, 440-8777 — or on fullscape sheets, three or four pages long. She signed off as “Didi”. In her beautiful handwriting and elegant prose, she talked about herself — the need for space and quiet in a bustling city, her ailments, the burden of the past — and political concerns — issues related to denotified tribes, the adivasis of Purulia and, elsewhere, caste violence and the failure of Left politics. She inquired about Anand’s family, recalled snatches of past conversations, demanded information and documents about the adivasi movement in Kerala, reflected on Anand’s novels and short stories, and remarked on the translations of his works.

A constant presence in these letters is a third writer, Akhtaruzzaman Ilyas, the Dhaka-based writer best known for his two novels on the Bangladesh liberation war, Chile Kothar Sipai and Khwab Nama. On their trip to Dhaka, Mahasweta had taken Anand to meet Ilyas, who was then in a terminal stage of cancer. He died soon after. She even took it upon her to translate a chapter of Chile Kothar Sipai into English and send it to Anand.

A dozen of these letters, written between 1996 and 1998 and which Anand had preserved, offer a fascinating view of Mahasweta Devi, her loneliness as a writer and activist and the struggle to balance the two selves. The letters stopped when telephony became easy and pocket-friendly.

In a letter dated December 7, 1996, her first to Anand, written immediately after their Dhaka visit, she calls him a writer’s writer. “I feel my Dhaka visit has been made worthwhile by knowing two very big and meaningful writers of our time. You, Ilyas. I am neither humble, nor a fool. I know I can still write if time permits. But my own brand of activism has ruined me as a writer. But I do not come into the picture at all. Ilyas I read, you one chapter two stories only. The six-fingered story and that chapter [samples of his writing Anand had taken with him on the Dhaka trip] have been xeroxed, become Ilyas’s property, etc. So, you have to send me ‘6 fingered one’. Junk I have. You have to write on. For I cannot, and Ilyas, who knows?” Junk was the first story by Anand she had read.

She had stayed on in Dhaka after the other writers returned to India to visit her ancestral village and to spend time with Ilyas. She writes: “I will surely translate your stories in Bengali and a few pages of Ilyas into English for his joy. The world I live in here in Cal. [Calcutta] is very ruthless. How happy I was there. Cal has already started swallowing me.”

Fragments from a lost time: In her first letter to Anand, she says, “I know I can still write if time permits. But my own brand of activism has ruined me as a writer”

Fragments from a lost time: In her first letter to Anand, she says, “I know I can still write if time permits. But my own brand of activism has ruined me as a writer”

She talks about visiting Ilyas every day during her stay in Dhaka, barring two days when she “went to Rajshahi, my grandfather’s crumbling house and a remote tribal area where about a thousand tribals awaited me”. “What have I ever done for them? Nothing. They never saw me. But the name was more than enough. It’s a fearsome burden too and I find it too heavy. Anyway, Dhaka is not Bangladesh. Villages here have no electricity. That village: No road, no school, crumbling houses etc. My cousin is taking 10 tubewells to that area… I saw the house where I was born, now a police outpost. Fed the police with choice sweets. All very happy…”

She asks Anand to visit Purulia, stay and work there for a few days. “Why? Because you are a whale of a writer. You are the Daroga Moinuddin (a character in Anand’s story, who is friendly with the peromboke people). Not many to command poets to go and serve the people, or perish.”

It is surprising that Anand, who had worked and lived in Farakka in Bengal for nearly 15 years from 1965 onwards as an engineer constructing the barrage across the Ganga, and Mahasweta, who first visited Kerala in 1981 to inaugurate the first convention of Janakeeya Samskarika Vedi, a cultural front of Naxalites in Kerala, had not met once before their visit to Dhaka. Anand, who speaks and reads Bengali, had also situated his second novel, Abhayarthikal (Refugees), set in the context of the Bangladesh war, in Farakka. A deeply philosophical work on the lines of Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain, Abhayarthikal is a reflection on war and exile. Having served in the General Reserve Engineer Force in the wake of the 1962 Indo-China war and in the army in the aftermath of the 1965 Pakistan war, Anand has been a witness to the human misery wars unleash.

It is a theme he returns to often in his fiction and essays. Like Mahasweta Devi, Anand was drawn to Ilyas because the Bangladeshi writer’s novels centred on the interplay of history and the present. When Ilyas passed away in 1997, Anand wrote a long essay, introducing the writer and his two novels to Malayalam readers. Though many Bengali writers, including Mahasweta Devi, have been translated into Malayalam, Chile Kothar Sipai and Khwab Nama await a translator.

Ilyas is a recurring presence in her 1996 letters. In a letter dated January 1, 1997, she writes, “I feel very depressed as Ilyas is not well. I listened to him. He said in a sleepy voice, ‘Now that you’re here, I’ll go to sleep.’ Then he said, ‘You have to translate my Sentry in the Attic, promise!’ I promised and he said, ‘Now I’ve to go to sleep.’ His mind is wandering. What shall I do Anand, if he dies? Why he? Who’ll fill the vacuum.”

There is an occasional reference, laced with humour and sarcasm, to the Jnanpith and Magsaysay awards she had received. “After a few hundred calls, interviews, TV interviews… how I wish I never received this. How to come back to daily routine? The table is like your Junk pile, telegrams etc. It is hell! But if you can get a xeroxed set of Delhi paper-cuttings, my son and brother will swallow it. They are behaving like loonies.” There is also a reference to calls from Bangladesh. “The Bangladesh people, and the younger writers telephone me, ‘We have won the prize, not you.’ Naturally, the Naxalite writers are most jubiliant. No movement, no meaningful work, yet they feel that they are true representatives of the people.”

Anand recalls Mahasweta Devi upbraiding him for not working enough. Action is what she believed in. “Your letter was full of hurt, too much hurt. Yes Anand. If you belong to that section (class) who have benefitted from independence, so, it is our duty to do our utmost towards self-atonement. By writing, why not? Jidhar tum khara hai, wohi tumhare liye tumhara ranakshetra hai. And do you not see me? Doing always too much, neglecting myself, zero to writing. But wait. I will, I will, the idea is germinating.”

Anand at his Delhi residence. (Source: Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Anand at his Delhi residence. (Source: Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

In another letter, she provides “good news from Purulia”. “3 Sabar girls have been appointed as homeguards. 30 women have attacked and beaten [the] landlord’s 8 henchmen. 8 arrested… After Delhi, I am going to open 10 functional literacy centres in many places. If I get a good press, I’ll surely talk of Sabars and ask for donations… we don’t want crores! Small schemes. A tank. Trees. A literacy centre. Some useful trainings.” “JP (Jnanpith) wants me to write to JP whom to invite. I can’t say PWG (People’s War Group), can I?” There is also a sentence scrawled in all caps in pencil, addressed to Ramani, Anand’s wife: “RAMANI, NO MORE SARIS Please. These will last till 2010 AD.”

A letter begins with the complaint that the telephones are not working. Then she adds: “Me and Akhtar (Ilyas) vowed to live till 2025, but I am convinced that I will die this year”. Every letter has some reference to the Sabars [a tribe in Bengal-Jharkhand], the crafts mela and tribal artisans. There is anger, lament, call to action, organisational issues that come up in reference to her work among the adivasis. She describes in detail the poverty in Rarh Bangla (a region that includes parts of the Murshidabad, Birbhum, Bankura, Bardhaman and Midnapore districts), the exploitation of the adivasis, the indifference of the state, the attempts at the grassroot level to organise and build institutions. In one letter, there is a reference to Anand’s Purulia visit: “You have left a host of admirers. Fuljhor offers you free food and a bed, so that you stay and finish the dam.”

Recently, Anand recalled that visit in an essay in Mathrubhumi Weekly. “One evening in 1997 December, we went from her rented flat on Ballygunge Station Road [Kolkata] and boarded a second-class compartment on the evening train to Purulia from Howrah station. No one on the way or in the compartment recognised her. But throughout the journey, whichever station the train stopped, people crowded at the platform window to see her. This went on till late into the night. A passenger, who looked [sic] a bhadralok, called me aside and asked who she was. I thought of saying, hajar churashir maa. When I said Mahasweta Devi, there was no response. I added that she was one of the foremost writers and activists in our country. The blank stare remained. When I mentioned the conversation to her, she pointed at the landscape outside the window, as if to make a comparison,” wrote Anand.

On January 4, 1997, Ilyas passed away. He was only 54. “Didi” wrote a short letter to Anand, which contains a translation of the obituary that the Bengali daily, Aajkal, ran. She added: “His wife Suraiya telephoned and said, ‘Had Didi not been there I’d never have met the writers from India.’ When I go, I’ll take the cassette, to listen to his roaring laughter and voice.” She also wrote that Ilyas had covered Bogura district (in Bangladesh) on foot in his student days and that, “as per his instructions he was taken to his village and buried beside his mother.”

Mahasweta Devi was so fascinated with Anand’s term, peromboke (which in Malayalam means unclaimed, non-revenue land and, in his novels, it stands for the landless who live on them) , that she would address him in a few letters as “Dear Peromboke Man”. “She took ownership of that word,” Anand says. In one of the letters, she wrote: “One peromboke person to another”.

She would also complain: “If the Kerala reporter didn’t come, I’d never have known that with the new generation, Anand is the ‘in’ writer… And you never told me anything about yourself. Why? Life is too brief to be so shy and withdrawn and modest. Didn’t you see me self-canvassing all the time?” It was on Mahasweta Devi’s insistence that Anand started to translate one of her early novels, Kobi Bandyaghatigoye Jeeban O Mrithyu, into Malayalam. “She said it was her best work. I felt the translation has come out okay. I consulted her and Nirmal Kanti Bhattacharya, who was then working on an English translation, when I needed clarifications,” Anand says. The translation fetched him a Sahitya Akademi award.

Anand with Mahasweta Devi and his wife Ramani. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Anand with Mahasweta Devi and his wife Ramani. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

In a letter (July 7, 1997), Mahasweta Devi recalled her experience of working on the book. “Kobi Bandyaghati was written in the Sixties, when I was living alone in a southern suburb in a small house, all alone, with a big 15th century tank in the front. Trees, paddy lands, coconut groves, birds, squirrels, mongooses abounding. The part-time maid left in the evening. Jackals howled, owls screeched, and reading till 1 am, I’d flash the torch to see if any snake had crawled in. The area was a snake kingdom. Had killed a few, even one vicious wild cat once. But I didn’t like killing. And my heart was all broken as I had to leave Nabarun [her son and the well-known Bengali writer] behind. Pining for him once I tried to commit suicide. Details someday. When I came to, I found Nabarun holding my hands. He told me, Maa, live, don’t die. We’ll meet surely. And I took to reading ferociously. Read Kabikankan Chandi. Knew he, dead in the 16th century, was waiting for me. And he opened my eyes and I found his brilliant use of Rarhbhumi Bengali, insight into Sabar life, their language. And wrote the book. Till date he remains my mentor. Black humour and savagery came later with the writings of 1980s and late 1970s. But I remain history bound. A lesser book like Aranya or 1084, too, are history.”

This letter, too, then moves on to talk about Sabars, women who had visited her, and the rains in Purulia. There is, of course, the impish humour on display as she signs off: “My own state government. No way to swallow me, or throw me out like an eaten fruit. Calcutta, as expected, is ugly with Tagore’s monsoon songs.”

Among the letters, there is a hand-written translation of an article she wrote for Aajkal on the Laxmanpur-Bathe massacre in 1997, “This valley of death is my country”. The caste and class repression, she writes, has “quite shaken the perombokians”.

In the years to follow, Anand met and travelled a lot with “Didi” — to Purulia, Gujarat, seminars in Bhopal and Hyderabad, Delhi. He also travelled to China with Nabarun, her son, who translated his novella, Nalamathe Aani (The Fourth Nail) to Bengali (Chaturtho Perekh). He recalls her 80th birthday, when she “gatecrashed” into his small flat in Delhi with Ganesh Devy and others to celebrate. Like Anand, Devy, the well-known scholar and cultural critic, had become a dear friend of hers. Once visiting Kerala to address a meeting on land alienation, she insisted on visiting Anand’s home village, Irinjalakuda. She had taken the rights from Sahitya Akademi to translate his novel, Govardhante Yathrakal, though Anand knew she would never have the time. In his novels of the last decade, Apaharikkappetta Deivangal (Stolen Gods) and Vibhajanagal (Partitions), “Didi” is an inspirational presence, evident in the concerns that he touches upon.

The two friends at a seminar in Dhaka, 1996. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

The two friends at a seminar in Dhaka, 1996. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

She had once written to him: “I have felt good, fresh, revived in your company. So let’s keep it up. Two writers fending for each other. It seldom happens in PV’s or Deve Gowda’s or Thackeray’s India.”

The last time they met was in October 2015, a few months before she passed away. “She had become immobile and memory had started playing truant. It had become difficult for her to speak on the phone. But the person was the same, cheerful and angry,” Anand, who turned 80 last week, recalls. Her life, Anand says, “taught me that certain deeds are not to be measured against success and failure, but they are just deeds that have to be done”.

More Lifestyle

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05