BUENOS AIRES—Sixty-eight million years ago in what is now Antarctica, there were no ice floes groaning or collapsing into an ice-covered sea. Instead the region had a moderate climate, temperate waters and a silence occasionally broken by the “hoink hoink” calls of prehistoric birds. That, at least, is the scenario suggested by Argentine and U.S. paleontologists who recently described in detail, in an article published in Nature, the oldest fossilized remains found so far of a syrinx—the sound-making structure of birds.

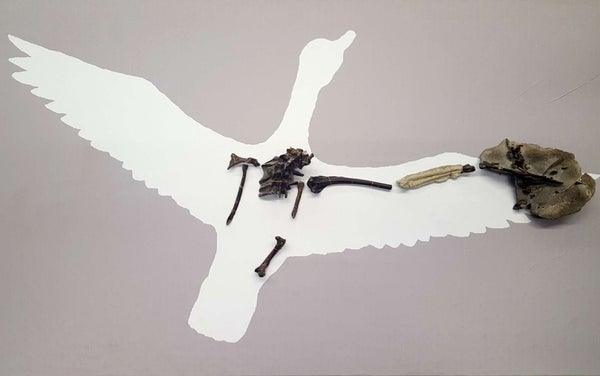

“This is the first fossil evidence of the vocalization apparatus of a bird of the Mesozoic era," says paleontologist Fernando Novas, a researcher at the National Scientific and Technological Research Council here. “It belonged to an extinct genus of birds called Vegavis iaai, which lived on today’s Vega Island, north of the Antarctic Peninsula. This animal was about 40 centimeters long, resembled a duck and coexisted there with the dinosaurs.”

Artist rendition of Vegavis iaai in their natural habitat. Credit: GABRIEL L. LIO, Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences Bernardino Rivadavia

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

It is not yet known exactly how birds evolved, how they learned to fly or how they diversified over millions of years to end up living among us. Paleontologists know that birds descend from dinosaurs, but not from all of them. “We want to know [about] that sequence, which began 240 million years ago. How is it that these animals with whom we share the planet today acquired their traits?” says Novas, who is also the director of the Department of Comparative Anatomy at the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences.

Until recently this field of work and study of the evolutionary history of modern birds was restricted to researchers from Germany, the U.K., the U.S. and China. But the latest findings in the Southern Hemisphere are changing this situation. This new work started in a territory whose omnipresent ice and low temperatures make for harrowing working conditions. “In 1992 we explored an area north of James Ross Island, about 60 kilometers from Argentina’s Antarctic Marambio base,” recalls geologist Daniel Martinioni of the University of Buenos Aires. “We noticed some 70-million-year-old rocks that showed a few hollow bones breaking the surface.”

After years of preparation and delicate removal of the rock, researchers realized they had in their hands the ancient remains of a bird. With the collaboration of U.S. paleontologist Julia Clarke, a specialist in the early evolution of these animals, the material was transported to the U.S. where it was “stripped” in a CT scanner. This was where Clarke, an associate professor at The University of Texas at Austin, found a huge surprise: Preserved among the fragile fossilized bones of this prehistoric bird there were pieces of soft tissue, specifically a section of the trachea and a series of rings that make up a syrinx.

The syrinx of Vegavis iaai seen in pale yellow in this image. This organ allowed the bird to emit complex sounds. Credit: J. CLARKE, UT Austin

Unlike other terrestrial vertebrates—including humans—birds lack vocal cords but do have a vocal organ, located in the lower part of the trachea where it divides into the bronchi; it allows them to emit a variety of sounds, from calls and cries to spectacular songs. “By comparing the three-dimensional structure of the syrinx with other fossils and 12 modern birds including ducks and geese, we reconstructed the evolution of this small organ,” Clarke described in the study.

Armed with this information, Novas and colleagues hypothesize that V. iaai, whose name combines the site of the discovery with the Spanish initials of Antarctic Argentine Institute, emitted squawks that might have been similar to the honking sounds of their living relatives. “This syrinx allowed them to emit complex sounds in order to be heard, defend territory or find a mate, and they used it in the same way modern birds do,” Novas says.

This research is also important because it reveals that birds such as V. iaai—which, despite having mostly terrestrial habits, could tolerate long periods underwater—were already highly specialized toward the end of the nonavian dinosaur era, when they wandered among the large creatures. “It shows that before the mass extinction that wiped out many of the dinosaurs on Earth along with two thirds of all living species, birds were already diversified,” Novas concludes. “And somehow, Vegavis managed to survive.”