On a June day in 1969 a very large man stood outside Northampton general hospital to pose for photographers. He was wearing jacket and tie, dark glasses and an eyepatch, and a broad grin. He also had a nurse on each arm; they too were laughing delightedly.

The man’s name was Colin Milburn and he was the most exciting cricketer in England. At least he had been less than a fortnight earlier. Then it happened: a late-night car crash; blood everywhere; the loss of his left eye; his career seemingly over.

Yet the most extraordinary part of the story came in the days that followed. Was he downhearted? Apparently not. He had been grinning throughout, telling jokes, cheering up his constant stream of visitors. His performance even made the hospital’s annual report: “His infectious good humour and indomitable spirit raised morale throughout the hospital.”

What we know now, nearly 40 years on, is that it was a performance, arguably both the greatest of his career and the most self-destructive. There was considerable competition on both counts. However, the greatness of his cricket had vanished for ever. The self-destruction would continue for another 21 years until he collapsed and died of a heart attack. He was 48. I still miss him, and so does cricket.

Next Thursday a new play will open, at the County Ground, Northampton – where I spent my teenage summer days mainly for the joy of watching him bat. We will have the chance again to celebrate and to mourn him; we will laugh with him again and, I can feel it coming, cry as well. The play, When the Eye Has Gone, is being co-presented by the Professional Cricketers’ Association and in November it will tour the 18 main first-class grounds. Had the PCA existed in its present form, its representatives would have rushed to his bedside not to be fooled by his cheeriness but to offer counselling and long-term support. It is an organisation that has become very aware of the dangers of despair.

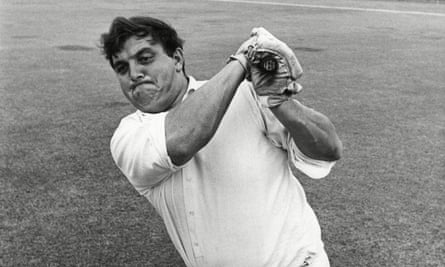

However, the play will also reflect the first and most important fact about Colin Milburn: that he was an absolutely fantastic cricketer. In an era when sixes had not been cheapened by repetition, he hit them regularly. He did not need a heavy bat: he was the heavy, about 19st of him at peak. He was not big-boned or bulked-up – he was fat.

But he was not a novelty turn. His technique was fundamentally correct, when he put his mind to it. However, when he decided a ball wanted hitting, it stayed hit. One-day cricket was a rarity in the 60s and he played little of it. But he still scored runs in any form of cricket at a thrilling, game-changing pace with formidable power.

He was also, for all his size, a genuine athlete. It is true he was once booed for his fielding in a Headingley Test but it was clottish to put him out deep. At short-leg, he broke Northamptonshire’s seasonal catching record. He bowled quite decent medium-pace. Once, after the eye had indeed gone, I umpired a benefit match in which he managed to smash a few for old time’s sake. And, at closer quarters than I had been allowed before, one could see that his greatness lay not in his power, nor even his poor old eyesight, but in his reflexes.

He came down from County Durham, then without first-class cricket, as an improbable prodigy, large even then. Northamptonshire trumped Warwickshire for his services by offering an extra 10 bob a week. He rewarded them by blazing across the game through the 1960s. He failed a lot, which is the way with such men. But when he was in, he was in. Once he had 20, it meant a business day.

England, with a deep breath, picked him against the mighty West Indies in 1966. He made 94 on debut and then 126 not out at Lord’s, to save the game. In two hours. In that match, he opened with Geoff Boycott, the most chalk-and-cheese opening partnership in history. But Milburn was never considered a regular choice until the time he was called out to Pakistan as a replacement and made 139 on a horrible pitch, an innings that everyone agreed would secure his place for the foreseeable future.

Strange phrase, that: foreseeable future. It was March 1969. Milburn’s future was just over two months away, and it was unimaginable. It is not just bias that makes me say that, of all the county players then in the business, he was the one the game most needed. A few weeks after the crash the Guardian’s revered cricketing sage, Sir Neville Cardus, walked out of the Lord’s Test: he was bored.

Milburn did try to make a comeback but the truth was that the other eye was also damaged, and he couldn’t do it. He tried commentary, for which he had a flair, but he couldn’t see well enough for that either. Eventually, he retreated to Durham and dwindled.

The loss of him as a cricketer was compounded by his outsize personality. If the cheerfulness was a mask, he wore it all his life. He was a very accessible hero for a kid to worship: he had a kind word for everyone and not a milligram of malice.

He was “good old Ollie” to the world. Life was a party, and he was happy to be at the centre of it, and there was always time for another drink (gin and coke, usually). And another. He had no enemies, except maybe himself.

Milburn’s personality is one area that fascinated the dramatist Douglas Blaxland, the nom de plume of James Graham-Brown, who himself bowled seamers for Kent and Derbyshire in the 1970s, just after the Milburn era. He then went into teaching and started writing plays in the 1990s, by which time he was a headmaster and thought his own name might inhibit his artistic freedom.

Since then he has written 40-odd plays, more than half of which have been produced professionally, none of them until now about cricket. He did, however, do a rugby play, Hands Up for Jonny Wilkinson’s Right Boot, working with the director of the new production, Shane Morgan. That led to conversations with the PCA who were keen to support a production that might help spread their agenda about the importance of players’ well-being, mental welfare and post-cricket futures. “Yes,” said Graham-Brown, “but I don’t want to preach. I want to tell a story.”

At that stage there was no actual story in mind but once the name Milburn was mentioned, it seemed obvious to Graham-Brown because that way it could be far more than a misery play: “He made so many people laugh, and the dark moments are private.” The flyer advertises “Songs! Anecdotes! A Large Gin and Coke!”, so it will be very Milburn. But it is set in a Durham pub as he looks back on his life from near the end, and a certain darkness is inescapable.

One of Graham-Brown’s best sources as he set out on the research was Alan Hodgson, Milburn’s Northamptonshire team-mate, flatmate and good mate, who himself died suddenly earlier this month, aged 64. This will add an extra layer of poignancy to Thursday’s performance.

Graham-Brown said Hodgson had reckoned Milburn was terrified of being alone. “It was always ‘everyone’s my friend, everyone’s part of my court, everyone’s welcome, everyone’s name remembered, everyone’s in this huge circle’. Hodge thought that even in the good days Colin would be low and dispirited if he was there in the winter and everyone else was away.”

As the play took shape, there was just one giant-sized problem: finding an actor. In the end, they opted for Dan Gaisford, who has what might seem to be one major disadvantage. He is not 19st, more like 12.

“I wanted to capture Colin’s personality rather than it being a tribute act. That wouldn’t have done justice to the script,” Morgan said. “This is not film, it’s theatre. We have a certain leeway in telling the story. We’re going to bulk Dan up a little bit but I didn’t want this to be about a fat suit. Colin belied all expectations. He was an athlete behind the frame.”

And this would be a test for any actor. It’s a one-man play but it includes 57 different parts. Gaisford will have to channel not just Milburn’s ripe quasi-Geordie but 56 other characters in his life as well. Hamlet in full and in Danish sounds like a soft option in comparison.

“I’ve been overwhelmed by the people ringing me up about Colin,” Graham-Brown said. “There’s something about this man that sets him apart. Everyone has very vivid powerful memories of him. Almost all happy memories.”

When The Eye Has Gone will be performed at all the 18 first-class grounds in November. Performances are also scheduled for Bath, Dorchester, West Hallam (Derbyshire) and Milburn’s home town cricket club, Burnopfield. Tickets for the county ground performances from https://www.ticketsource.co.uk/the-professional-cricketers-association

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion