It’s been a year dominated by a much-needed conversation about diversity within popular culture. Despite what straight white Brobusters might have to counter, the importance of representation on screen has led to a greater awareness of the stories Hollywood hasn’t been telling.

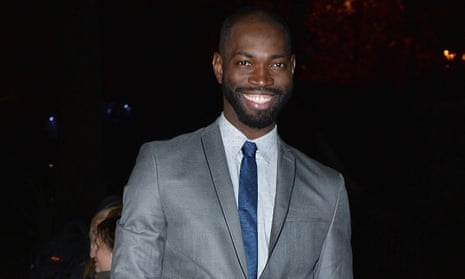

No film justifies the need for such variety quite so convincingly as Moonlight, a soulful drama from director Barry Jenkins about the life of a black gay man growing up in Miami, told in three heartbreaking chapters. Tipped as an Oscar favorite, it’s breaking thrilling new ground yet away from the glamorous red carpet premieres it’s received at Telluride, Toronto, New York and London festivals, the true story at its core is something far removed. Based on the autobiographical play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue from award-winning playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney, it tells of a boy struggling with an addict mother and a school rife with homophobia.

Given the long journey that your story has taken from the stage to screen, how much do you still recognize from your own experiences?

The original script was different in form, in terms of the three chapters were told simultaneously so in that way it was different. However there’s a lot in it that is the same. Barry worked really hard to preserve some of the original voice and I think what he also did is work hard at putting a lot of space between it. It feels ultimately personal, even the parts that I didn’t write feel personal because I feel like they are connected to the same story, the same struggle, the same questions. It doesn’t feel foreign at all, in fact sometimes it feels too close.

Was it a difficult experience finally watching the film?

The first time, no. I think I was just so excited to see something that looked exactly like memories to me. Then the glee of that wore off – and I did remember feeling very depressed and very heartbroken about a lot of it. Mostly because these are not things that I have found the answers to and understand how they work. I actually ended up feeling that these are still looming questions in my life, questions about my own identity and my own self-worth that I’m still trying to figure out. Then seeing the film again, I was like shit, these are still here and they’re not going anywhere.

It is about the big issues like identity and homophobia but also, I don’t know if I’ll ever be done trying to suss out the trauma of growing up with an addictive parent. I don’t know if that will ever go away but I wish like hell that it would. It is difficult to watch and re-engage with but ultimately necessary because it’s brought to bear some very serious questions for me. Also, even in my career, why aren’t I telling more intimate stories? I feel like I tell intimate stories in plays but why am I not telling stories like this that lay me bare. Not exploitative but just getting at the sort of hard truths of things.

There are so many important LGBT stories that have been straight-washed on the big screen. Even though many of the themes are universal, how reticent were you to hand the project over to a straight writer/director?

Barry had tremendous respect for what the piece was. He never came in trying to turn it into something else. In fact, he dug his heels in about certain things that were not going to go away. There was no reticence with Barry. He also didn’t ask any of the actors if they were GLBT-identifying, he just cast them. We were telling a coming of age story that was dealing with queer identity and nobody tried to sideswipe that. It’s happened in other instances but not here. We knew that there were not going to be any white characters in it. There were no white characters in the original script. It’s just very difficult for you to see white people in Liberty City (the area shown in the film). They knew that and they were more than cool with it. My reticence was more about how much to say and how much is necessary in order to make the story as authentic as possible.

The film’s had universal acclaim, but there have been some negative comments about the film being an offense to black masculinity by commenters on YouTube and I know Barry was trolled a bit on Twitter about it. Why do you think this very specific type of homophobia is still such a problem?

First of all, I know that there’s homophobia that is essentially misogyny masked as homophobia in all of American culture no matter how much we try and pretend there is not. That anti-feminism is rampant and I think when it comes to someone’s notion of what a black man should be like, it again is tying back into this understanding and it’s people who feel like there is a way to be masculine and that masculinity means a kind of superiority which is just misogyny. So I think that’s endemic in all parts of American society and it just comes out in different ways. I don’t think it’s particular to black culture. It may show itself differently but it’s all part of the same thread.

As well as regulating your behavior as a gay man, do you also feel like you have to be careful of your behavior as a black man in America? That you need to perform in different situations to survive?

My gayness doesn’t give me any pass. I’ve still had the police pull me out of a car, put guns to my head, lock me in handcuffs and leave me face down in the pouring rain for no reason. Until they go into my back pocket and see some sort of white privilege in there, which is probably a university card or something and then they’re like “oh maybe we’ve got the wrong person”. There’s no gay card that gets you off the hook. People suggest that there is but I know, with empirical evidence, that there isn’t.

In the film, we see a moment when Chiron’s guard comes down and he seems more comfortable with his sexuality. Was there something similar for you when you came out?

It’s interesting because I never had a coming out moment. Especially because, like in the film, people were telling me I was gay from the off. There was never a moment when I had to sit everybody down and have a conversation. There were these small moments when I would be with my boyfriend and have to explain to my brother that this is my boyfriend, he’s not my friend or my partner but he’s my boyfriend. My brother was like “oh cool” and we moved on. There was a moment when I was being intimate with women and intimate with men and something happened where I realized I wanted to be more than just intimate, I want to be in a relationship and who I want to be in a relationship with is men. That’s what being gay is to me. So then I was like OK that’s cool and I understand why they’re calling me gay.

You were also coming to terms with your sexuality at a time when there was a dearth of gay people in the media, especially gay black men. Do you think that kids coming out now will have a different experience because they can identify more easily with characters and figures within popular culture?

I think so but I often don’t like to put the burden of total representation within art. Art is there to reflect. The problem is that we’re not being totally representational within life. Like you said, when I grew up there was a dearth of gay people in the media but there were gay people within my neighborhood. There were transgender people within my neighborhood. The way in which the community interacted with these people was so peripheral and marginalizing that I didn’t get a chance to know how they could be integrated into the world around us. That’s on us as a community and us as people. It’s important for us to be representational as people in communities and not get this xenophobic idea of living in this homogenized world.

Even within those representations we see, there is still often a more “acceptable” definition of what a gay man is seen as by society, in terms of either masculinity or femininity.

That’s equally problematic on both sides. Often in America we get accused of only showing the masculine, normalized heteronormative gay and then there are people who are feminine, male or female, because gender has nothing to do with masculinity or femininity, and we marginalize them so much that people only see that life for themselves. There are feminine straight men and there are masculine straight women. In terms of allowing ourselves to be more fluid in our day-to-day lives, we can’t just rely on universality within art to happen. That’s crazy. Although that doesn’t give us a pass. We have to be thinking about it because we have the ability to make the world we want.

Moonlight is out now in New York and Los Angeles with a UK release to be announced.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion