‘Besides feeble writing, there is a mixture of tragic-comedy and buffoonery in it, which Apostolo Zeno and Metastasio had banished from serious opera’. You can always rely on Charles Burney (the celebrated musicologist, who spent most of the 18th century being professionally underwhelmed) to find fault. But writing here about Handel’s Xerxes he has a point. The opera’s blend of lighter and more serious elements, though typical of Venetian opera, was by no means the norm for the Londoners who were its audience. They didn’t like it then, and nearly 300 years later it’s something we still seem to struggle with, as English Touring Opera’s latest season makes unexpectedly clear.

The all-Baroque programme for ETO’s autumn tour brings its revival of Xerxes together with new productions of Monteverdi’s Ulysses’ Homecoming and Cavalli’s La Calisto — works that offer three very different answers to the same basic dramatic equation: what happens when you add grubby lust to noble love, low comedy to high tragedy?

If this were Shakespeare we wouldn’t even bother doing the maths. You can no more take the darkness out of A Midsummer Night’s Dream than you can the comedy out of The Tempest; so why are expectations so different when it comes to early opera? Perhaps because it’s much harder to sustain that degree of emotional sophistication in song, to create coherent character in the stop-start dramatic medium of recitative and aria. That these three operatic masters all achieved it is an extraordinary feat, and one that deserves better than to be undone by unsympathetic direction.

Timothy Nelson’s Calisto swaps Ovid’s woodland groves for a run-down steampunk playground. Giove (George Humphreys) makes his entrance on a slide, while would-be lovers Linfea (the unnecessarily cross-cast Adrian Dwyer) and Satirino (Katie Bray) frolic on the seesaw. It’s a striking, stylish framework that’s full of promise, but one that unfortunately ends up infantilising its material, transforming Cavalli’s erotic, throbbing dances into chaste, childish games, and smoothing a spiky tragicomedy into highly polished farce. It’s funny (ish) but at what cost?

Nothing is more unsexy than camp, and from Nick Pritchard’s spangly-suited, tutting Mercurio (beautifully sung) to Giove’s outrageous cross-dressing, this is Carry On Calisto. Camp is the prophylactic with which we sheath obscenity, but Cavalli’s exhilaratingly frank portrait of human sexuality and desire shouldn’t require any such euphemising coyness. Comedy here undercuts the sincerity, the weight of every relationship, from the tender affections of Catherine Carby’s warmly sung Diana and Tai Oney’s Endimione (styled as Galileo by way of Einstein) to Calisto’s (Paula Sides) misdirected ardour for her goddess. Musically things are better. Cavalli’s compact orchestration works well for ETO’s young singers, though Nelson’s tempos also tend to the staid, tying the hands of the excellent Old Street Band, and not in a kinky way.

But if Nelson’s Calisto refuses to drop its panto-grin, then James Conway’s Ulysses has the opposite problem. This most Shakespearean of Monteverdi’s operas jumbles gods and mortals, sottish spongers, simple shepherds and monarchs together in an operatic tapestry as deftly woven as Penelope’s own. But lose one of its many-coloured threads and it can easily unravel. Aside from the inevitable cuts (deep, many), there’s a tonal issue here. Both Conway’s direction and Takis’ sets and costumes insist on lofty abstraction, forgetting or erasing the anarchic vulgarity that must co-exist here. Adam Player’s Irus is positively tasteful, and even the scheming suitors are played as legitimate lovers. The decision to conflate one of them with Melanto’s servant-lover Eurymachus, so the same man woos both maid and mistress, is interesting, but one whose dramatic aftershocks threaten to destabilise some of the work’s moral absolutes.

Carolyn Dobbin’s Penelope sings with all the balmy ease her character rejects, softening the delivery if not the essence of this unyielding figure. She’s well partnered in Benedict Nelson’s Ulysses — a gentler, younger hero than most, retaining more of his emotional warmth, and achieving a lovely unforced intimacy with Nick Pritchard’s outstanding Telemachus. Katie Bray — the performer of the season — once again shows her quality as Minerva.

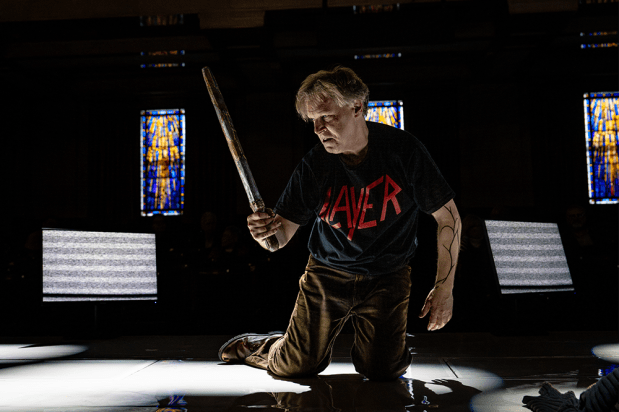

Conway’s Battle of Britain Xerxes looks much as it did when it premièred in 2011, and sounds similar too thanks to repeat performances from Laura Mitchell’s glossy Romilda and Julia Riley, charismatic as ever in the title role. If anything, though, the comedy has intensified, tipping over into Burney’s ‘buffoonery’ more than once thanks to a phallic windsock and some St Trinian’s-style hijinks between Romilda and Galina Averina’s pert Atalanta. The result is genuinely funny and intermittently charming, but risks betraying both the darker shades of Handel’s original and the even bleaker echoes of Conway’s new setting. To make light of the Blitz is one thing, to do it in Hackney, in the heart of London’s old East End, seems like a collision of contraries that might just go too far.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in