Chekhov, Bulgakov, Conan Doyle, Somerset Maugham; more recently, Michael Crichton, Abraham Verghese, Khaled Hosseini: these are just a few of the best-known doctors with second careers as creative writers. I’m one myself. I’ve been in practice for 25 years, and have five novels and a scattering of literary prizes to my name.

What is the link? Doctors are privileged with a ringside seat during every one of life’s landmarks – pregnancy, birth, childhood, marriage, divorce, employment, redundancy, illness, ageing, bereavement, death. We see these acted out in countless different families and lives; there is no end to the inspiration for character and story. And, as generally empathic people, most doctors have strong emotional reactions to the things they encounter professionally. Chekhov wrote: “A doctor has terrible days and hours … these terrible hours and days that I am speaking of only happen to doctors.” Ethan Canin would agree: “It’s like being a soldier. You’ve seen great and terrible things,” he told one interviewer.

There is more to the striking overlap between medicine and literature, though, than exposure to a wealth of arresting material. During our time as medical students, much of our energy is devoted to mastering the sciences – anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pathology. Yet, by having repeatedly to present cases to consultants on teaching rounds, we are without realising it being schooled in a very different art.

I remember how, in my first couple of months on the wards, I struggled as much as anyone to marshal the vast quantities of information I would discover about each patient. I also remember vividly the day things clicked into place. I’d spent the morning “clerking” a man with jaundice, and much of the afternoon listening to my fellow students giving their own cumbersome presentations – and witnessing the boredom and irritation of our consultant as he tried to maintain his attention. When it came to my turn, I was struck by sudden inspiration. I edited and rearranged on the hoof, zeroing in on the key positives and negatives that supported the diagnosis I would conclude with, shuffling them into an order that served ineluctably to paint the picture I wanted to portray. It was short. And it was sweet. When I finished, the consultant gave me a broad smile, and simply said: “Good!”

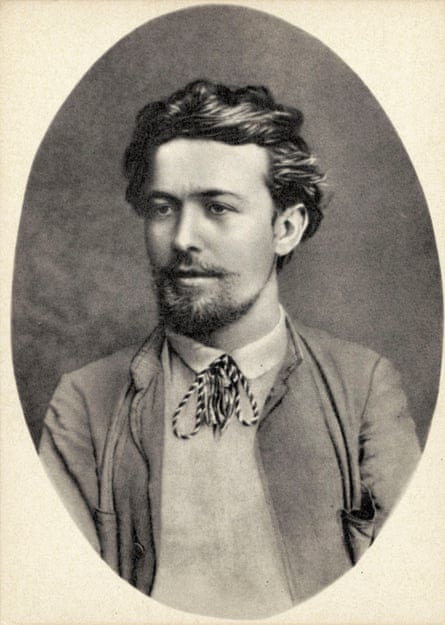

I didn’t realise it at the time, but what I’d worked out was how to tell a story. Each patient’s illness is a narrative – symptoms as the beginning, diagnosis as the ending – and a middle that weaves a coherent and irresistible path between the two. This aptitude for narration is essential to those doctors who go on to write, but it’s a moot point whether medical training actually endows it. Grigory Rossolimo, a renowned Muscovite neurologist who studied alongside Chekhov, recalled that the author “did not go to work as an average medical student. He collected the elements of the case history together with surprising ease and accuracy.” Perhaps the process of learning to become a doctor draws out an innate capacity for storytelling in some individuals.

Over the course of our careers, we become highly attuned to the multifarious ways by which people communicate. The medical consultation, dealing as it does with subjects that are often difficult to express honestly and openly, represents a masterclass in linguistics: the way imagery and metaphor – and repetitions, omissions, rejoinders, non sequiturs, hesitations, and silences – convey more meaning, and can be more revealing, than mere words. Then there is the language of the body: how posture, eye contact, appearance, and mannerism can underscore or belie what is being said and not said. All this feeds into our dialogue and our portrayal of character.

While our empathic responses to the “great and terrible things” we witness can be strong, doctors have also to develop dispassion in order to survive emotionally. This ability to feel what others feel, and simultaneously to view it with detachment, gives us perhaps our greatest strength as writers. In discussing Chekhov’s work in art and medicine, Rachel Hajar notes that he portrays his characters with “the objectivity of a scientist and a physician combined with the sensitivity and psychological understanding of an artist.” Self-evidently, very many writers achieve greatness without ever setting foot on the wards, but as Somerset Maugham said: “I do not know of any better training for the writer’s profession than that of spending time in medicine.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion