- India

- International

Jealousy, that least heroic of human failings, has always been of great interest for me: Amruta Patil

Writer Amruta Patil on working on another book based on the Mahabharata, leaving cues to journeys that remain unmentioned in the writing and the cyclical nature of history.

The story is in the telling: Amruta Patil. (Source: Mark Sequeira)

The story is in the telling: Amruta Patil. (Source: Mark Sequeira)

In the Author’s Note of her 2012 book, Adi Parva: Churning of the Ocean, Amruta Patil wrote, “A good storyteller, like a good teacher, speaks in the language of the hour. Her only allegiance is to the essence of the tale; the essence safeguarded, she is free to improvise the narrative to reflect the time.” These lines can be read as an instruction, but they can also be seen as a promise — one that Patil stays true to. Her masterly control over the vast storytelling material that the Mahabharata represents ensured that Adi Parva, narrated by Ganga, was at once a timeless epic and a reflection on our present, resonant with contemporary concerns about gender politics and ecological degradation. With the second part of the retelling, Sauptik: Blood and Flowers (Harper Collins), releasing on October 20, Patil hands the threads of narration into the hands of a wounded, damaged mortal — Ashwatthama — bringing a new urgency to the tale. Excerpts from an interview:

In Adi Parva, you wrote in detail about the importance of sutradhars in relaying a story through the ages. Could you tell us how you settled on Ganga and Ashwatthama as your sutradhars?

I wanted Sauptik to be what Adi Parva is not: passionate, embarrassingly personal, even as it periodically nudges the multiversal. And so I chose two sutradhaars who were as far apart from one another as possible. Adi Parva’s Ganga is a sublime river goddess, a queen, an unsentimental mother who can drown her babies unflinchingly. She straddles the worlds, involved and detached at once. There is nothing sublime about Sauptik’s Ashwatthama. He is the anti-Ganga: a warrior who could never be the best; roiling, insecure man who spent his life yearning for his father’s approval, who assassinated his childhood friends’ sleeping children. In this character, wracked by jealousy and a hopeless quest for validation — I saw the most human of struggles. Jealousy, that least heroic of human failings, has always been a subject of great interest for me.

The Mahabharata is vast, swollen with stories and themes. How did you condense and contain all that material, without losing narrative richness?

The choice of sutradhaar is a natural editorial filter. Then, there is the natural filter imposed by what my preoccupations and fixations are at that given phase in life. In Adi Parva, the central theme was organic ontology; the internalising of metaphors, for example, devas and asurs, being a reference to your own oscillation between trained reflexes and base instincts. The importance of penance, tapas, was a big thing for me in that book. In Sauptik, the central theme is aligning oneself with natural elements; the choice one needs to make between making your life a ranabhoomi or a rangabhoomi (battlefield or playing field). The parch of Adi Parva gives way in Sauptik to a flowing of life juices, it is rasa-replete!

Even as I approach the lore with clear-eyed enquiry, the irreverence is always tempered by respect. I am aware of the perils of oversureness, of hijacking the lore overtly for propaganda. I am aware of my tendency towards posturing and hubris. I guess the continuous knowing keeps both, my work and person, in check.

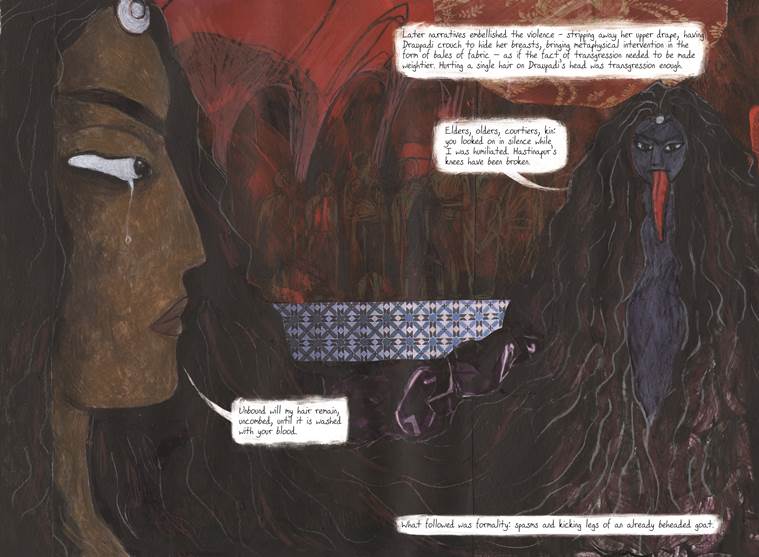

Panels from Sauptik: Blood and Flowers — Draupadi’s Wrath. (Source: Mark Sequeira)

Panels from Sauptik: Blood and Flowers — Draupadi’s Wrath. (Source: Mark Sequeira)

In Adi Parva, one of the ideas you explore is that of ecological damage. How do you take this further in this book?

A sutradhaar necessarily belongs to her time and context. Her stories gently shift course to address the fears and preoccupations of the hour. I guess that explains the tack chosen in these books. In any case, the avatar story is very much an ecological tale: Vishnu’s alliance with Bhoo Devi and Shree Devi, so it wasn’t a far stretch. In Sauptik, Ashwatthama observes that as the forests around him start thinning, they start to grow denser in his narrative. There is Yamuna, loyal backdrop of Sauptik, whose waters start growing darker and oilier with the turning of times. There are the Pandavs and Draupadi, born of five elements. But most of all, there is the visual treatment of the book. It is an unabashed love note to soil and water, fire and flower.

There are many art historical references coded in the artwork of your books — from the foliage inspired by Indian miniature traditions to Botticelli’s Venus and Henri Matisse’s La Danse. Why is this important for you?

Adi Parva and Sauptik — and, to a lesser extent, Kari — are determinedly open-source in the DNA. Visually, this means there is a lot of crosstalk going on between my work and the work of those I aspire to (more or less) be in the lineage of. It is my way of leaving love notes and cues to journeys that remain unmentioned in the writing. You will meet them all, if you look carefully enough. Pierre Bonnard and Diego Rivera. Roerich-esque mountains and skies, Kalighat-style Hanuman, gopis that reference abhisarika nayika (from the ashtanayika pantheon), war scenes whose composition echoes sculpture from Angkor Wat, colours and forms from Tantric Vajrayan imagery. Collage pages that use textile and bijoux elements from fashion magazines. The red corridor that Dusshasan drags Draupadi along is painted atop a found image of Saddam Hussein’s palace. The aim has always been to fuse the traditionally timeless with the contemporary in a way that isn’t grotesque and hackneyed.

What media did you use for the artwork in Sauptik? What are the continuances from Adi Parva?

I have worked with acrylic paints, collage, watercolour, charcoal. The visual form of Sauptik is more of a hybrid than Adi Parva. There are text pages adorned with just a spare illustration, black and white pages where sutradhaar Ashwatthama interacts with his audience, and colour pages. The most important difference is that there are no boxy panels in Sauptik. Events on a page flow seamlessly, on a single page, the way they would in an Indian painting from Kangra or Rajasthan. I kept the lush colours of Adi Parva, but worked on greater control of surface and line and I used more collage because it works well in print.

Using different art styles for different story strands within the book is a great way to give visual cues to the reader.

How could the same colour palette possibly straddle, both the nacreous colours of Devlok and the bloodbath of Kurukshetra? I have my technical limitations, but it was obvious that I needed to engage with all the nine rasa if the story had to unfold the way I wanted it to. Also shifting visual styles gives it that story-inset-in-story feel so particular to our storytelling traditions.

Panels from Sauptik: Blood and Flowers — Raas Leela. (Source: Mark Sequeira)

Panels from Sauptik: Blood and Flowers — Raas Leela. (Source: Mark Sequeira)

In one of your podcasts, you mention that three years after the book was published, you found the central image of Adi Parva (emergence of Padmalakshmi) a lot less harmonious than you did before. Has time similarly changed your perceptions about certain other aspects of the book?

There is a guileless, unselfconscious quality about early work that can never be replicated again. (You may attain the ease that comes with mastery, but it is still not the same thing). That said, there is the business of growing up. I am not the same person now that I was during Kari or Adi Parva. I recognise flaw and immaturity and inadequacy in some narratorial choices. This makes it exceedingly hard to revisit my old work. But one learns to live with this: ‘That was the best I could be then. This is the best I can be now.’

Retellings are particularly important in India right now, given how our readings of the epics, Vedas and Puranas are getting narrower and narrower. Was this ever a concern while working on your books?

I have read history enough to know that moments of inflorescence and fertile abundance are followed by moments of barrenness and great parch — this is as true of world cultures as of trees and fields. That these things are cyclic doesn’t lessen the need to be vigilant and watchful of what happens, or to do one’s bit as a gardener. I know that the source material I work with is lush with the juices of life, it is polyphonic and rich. The idea of vibrant, life-affirming material being desiccated and stunted by half-informed bigots with no inner life, is hard to endure. Not on my watch!

What were you reading and watching while working on Sauptik?

My influences aren’t from the visual storyteller’s or mythologist’s canon. Unpredictable books have fired my synapses — and marked my work — in the last few years. Nassim Nicolas Taleb’s Antifragile, William Bryant Logan’s Dirt: The Ecstatic Skin of the Earth. Bernard Werber’s Empire of the Ants, Roberto Calasso’s Ardor. Tarun J Tejpal’s The Story of My Assassins. Frank Herbert’s Dune books. Arthur C Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey — lot of non-fiction, popular science, science fiction, some poetry. These are my sustenance and benchmark. The lateral sprawl of ideas, the panoramic scope of vision, the lion voice: this is like a galactic journey for me. I also watched humans quietly and continuously, online and offline.

Having lived with the Mahabharata for so many years, what is next for you, now that Sauptik is out?

I have some specific, detail-oriented goals: fixing logical fallacies, figuring out the methodology of writing nonfiction, learning certain technical aspects of painting. But the overall intent remains the same — to be an observer of life, beauty, the fears — hungers-neuroses of people (including myself).

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05