Lav Diaz’s The Woman Who Left is a vast, dark behemoth of mystery and anguish, as forbidding as a starless night sky. This is the film that won Diaz the Golden Lion at this year’s Venice film festival and took the Filipino director’s global reputation to a new level. Running as it does at a mere three-and-three-quarter hours, it is a squib compared to his other works, such as the eight-hour A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery, which he premiered at Berlin in February.

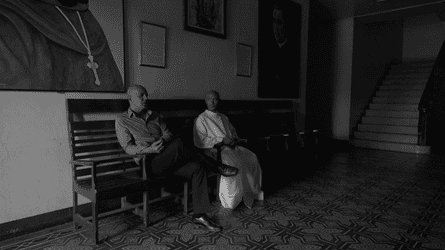

Its forbidding sombreness makes it a challenge until the viewer recalibrates their expectations of rhythm and tempo; you must readjust to something slower even than the walking pace of conventional social realism. Diaz works on the movie equivalent of geological time. His movie has no closeups – there is just one medium shot of his heroine – and it is strange to come to the end of such a long movie with only a hazy idea, or none at all, of what the characters actually look like. It is in austere monochrome, made even more daunting by Diaz’s love of darkness in all senses – his unhurried, unlit sequences are something to compare with Pedro Costa’s sepulchral images of Fontainhas in Lisbon or Tsai Ming-liang’s street scenes. It’s a film you have to feel your way into, like a ruined church or a haunted house.

Diaz here returns to the inspirations of classic Russian literature – guilt, shame, the burden of forgiveness, the existence of God, the search for Christian grace. His Norte, the End of History was freely adapted from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. The Woman Who Left is inspired by (rather than strictly adapted from) Tolstoy’s short story God Sees the Truth, But Waits. (By the end, it reminded me more of Father Sergius.)

In Tolstoy’s story, a merchant grows old in prison, having been wrongly convicted of murder as a young man; a middle-aged criminal arrives, boasting of his life of wrongdoing, and from the details, the old man realises that he is the actual culprit.

Diaz takes the idea on from its endpoint: it is 1997, radio news reports announce it to be the era of the Hong Kong handover and the deaths of Princess Diana and Mother Teresa. There is poverty, crime, kidnappings. (It is not mentioned, but this is when Rodrigo Duterte was beginning his tough-guy political career in the Philippines.)

Horacia (Charo Santos-Concio) has served 30 years for a murder she didn’t commit. Then the actual culprit – who was Horacia’s friend – commits suicide in prison, leaving behind a confession, revealing that Horacia’s ex-boyfriend Rodrigo Trinidad (Michael de Mesa), now a wealthy gangster, was behind it all, and had her framed.

Horacia, institutionalised and having long since lost touch with anyone on the outside, is briskly released. The sole expression of official regret is the female warden’s motherly, sorrowing moans of: “Sorry, so sorry…”

Horacia comes home to find that her husband is dead, her estranged daughter runs a stall and her son is missing. So she sells her modest property and heads for the big city where Rodrigo is in the habit of attending mass in the cathedral – and she buys a gun. A hunchbacked vendor of balots, bird embryos sold in their shells as street food, tells her about the rich criminal classes swaggering around among the poor. A lonely woman with mental difficulties befriends her and shows her the cathedral. We appear to be inching, slowly, towards payback.

Then a kind of miracle happens: Horacia befriends a transgender prostitute called Hollanda (John Lloyd Cruz) who has been badly beaten up. Looking after this poor soul becomes her new mission – and she realises that this has allowed her to rediscover a moral meaning to her life.

The themes of God and judgment are all around. The balot seller tells Horacia that he believes God has cured his sick child. She has many conversations with him in the fathomless darkness. She tells him: “I really am a creature of the dark.” “A vampire?” he asks. When he is beaten up by a hoodlum wielding a gun, Horacia demonstrates to him how to disarm an assailant. “Where did you learn to do that?” he asks, astonished. “In the dark,” she replies – that is, of course, in prison. But Horacia has been in the dark all her life: a long dark night in the Garden of Gethsemane.

As for Rodrigo, he too is troubled by the existence of God and the suspicion that he hasn’t got away with anything. He asks the priest where God is. “You must find him,” says the priest.

Horacia, who before her imprisonment was a writer and teacher, seems in some ways to be returning to her vocation. She is finally seen reading to some children, the way she taught literacy to the women in jail. Her story is about “a dream which stayed in a hidden world”. Perhaps that applies also to this massive, enigmatic, deeply serious film. It requires a huge investment of attention – but repays it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion