“The story of Los Angeles that’s put out there comes through Hollywood. It’s the story of the Dogtown Boys or Beverly Hills 90210 or reality TV shows in the OC. That becomes the story of young people in LA,” says Pilar Tompkins Rivas, director of the Vincent Price Art Museum. “For more than half of the people who grow up here, that’s not their story.”

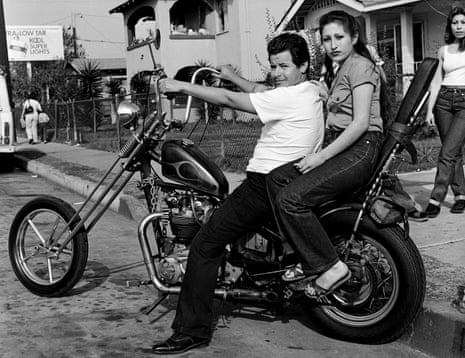

To offer an alternative to this exclusionary narrative, Tompkins Rivas organized the exhibition Tastemakers & Earthshakers: Notes from Los Angeles Youth Culture, 1943-2016, which will open on Saturday at the museum. Through a multimedia presentation that includes contemporary art, documentary photography, historical ephemera, fashion and music, the show focuses heavily – but not exclusively – on the Latino experience as lived on the city’s Eastside.

“I didn’t want to get too caught up with geographic boundaries because that’s reductive,” said Tompkins Rivas. “I didn’t want it to be an exhibition that’s too restrictive in terms of being Latino. I wanted to bring in some points of intersection.” That diversity is certainly on display and the show documents the influence of British youth culture on Latinos, juxtaposing photographs of British Teddy Boys with zoot-suited Mexican American youth, known as pachucos. An image of a snarling Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols hangs next to one of east LA punk pioneer Alice Bag looking just as fierce. The Japanese community of Boyle Heights is also represented, including one image capturing them in zoot suits, that was actually taken in a wartime internment camp.

The starting point for the exhibition is the zoot suit riots of 1943, a series of violent clashes between American servicemen and the pachucos, on the streets of LA. To the pachucos, the baggy, finely tailored zoot suit was a symbol of pride, a way to assert their identity. To the soldiers, however, the luxurious outfits were an unpatriotic flouting of wartime wool rationing. More than a few pachucos had their suits forcibly removed and destroyed by the GIs.

Alongside period copies of Time magazine and the LA Times that decried Mexican American youth conspiring with Axis powers, the exhibition features a dramatic painting by Vincent Valdez that depicts a bloody bar-room brawl between sailors and zoot-suiters. Raised in San Antonio, Texas, Valdez had never been to LA when he painted the work and knew little about the riots beforehand. “It really struck a chord with me,” he said. “I wondered why I had never been informed about this, why it was never in my textbooks.”

Although the fashions may be different, Valdez sees clear parallels between this conflict more than 70 years ago, and current racial tensions. “It was nothing more than racial profiling, very similar to what we have today,” he said. “Instead of baggy jeans and hoodies, it was baggy slacks.”

As Tompkins Rivas explained, beginning with this event not only serves to explore a significant moment in Latino history, but also illustrates the fluidity and exchange between cultures. “When you look at it, the same kind of social and economic constructs that gave rise to Teddy Boy culture in the UK, gave rise to zoot suit culture in LA,” she noted. The influence of British music and fashion is a common thread throughout the show, from rockabilly to punk to the rave scene and even Morrissey, who has a large and notoriously passionate Latino fanbase in east Los Angeles.

For artist Juan Capistrán, being part of an underground musical scene was an important part of his identity. “Speaking from the perspective of being an immigrant, I gravitated to subcultures as a way of forging a new identity that was different than what I was experiencing at home,” he said.

His Woody Guthrie-quoting piece, This machine kills fascists (love is the message, labor sets you free) (2010), is a scale model of the hacienda-style house he grew up in, and where his parents still live, in South Central LA. A large speaker fills the model home’s backyard, recalling the backyard parties he would attend growing up.

“There are a lot of references to points in musical history, specifically house music,” he recalled. “How it originated from the disco scene and how that was predominantly for people of color, marginalized people. How it gets exported to Europe and comes back, and how I experienced house music in LA in my early teens.” Fittingly, the “hacienda” is also a play on the legendary Haçienda club in Manchester that showcased underground dance music in the 80s, from New Order to Happy Mondays.

Sandra de la Loza also explores the way youth establish communities and spaces for themselves outside of the mainstream. Her Stoner Spaces photographic series captures bucolic landscapes in east and north-east LA that have been adopted and transformed into informal gathering spaces. “These forgotten, abandoned interstitial spaces have historically been super important for Chicano/Latino youth to enact their agency,” she said, “to find a piece of freedom without the vigilance of authoritarian regimes like educational systems, systems of policing”.

These were places where a broad range of subcultures could congregate, from ravers to metalheads and punks. That is, until the crack epidemic and associated gang violence brought the increased scrutiny of the police. “For the most part it was semi-tolerated,” said De la Loza. “In the late 80s, the youth and these spaces began to be policed more, so it kind of ended that type of culture and these more visible occupations of space.”

This points to another important theme of the exhibition: the criminalization of youth that runs from the pachucos straight through to the gangsters of the 90s and up to the present. “You can point to all these instances that have really affected young people of color in LA: 1943; 1965 the Watts riots; the Rodney King riots in 92; the Rampart scandal in late 90s, and Black Lives Matter today,” says Tompkins Rivas. “It’s a cycle that gets repeated over and over again.”

Fashion again plays a large role, as certain kinds of clothing or hairstyles were outlawed, some of which are on display here. Alongside a selection of zoot suits selected by Barrio Dandy, AKA John Carlos de Luna, there’s an assortment of T-shirts, sneakers, and ephemera associated with the SoCal 90s party crew scene, which Guadalupe Rosales obsessively documents as part of her Map Pointz archive.

With his photographic series Chico, Dino Dinco problematizes the issue of sexuality and gender, presenting portraits of men that reflect a sense of ambiguity regarding sexual orientation. “I had long been interested in the kind of fraught masculinity around the idea of the homeboy and the relationship to queerness,” he said.

“Queer Latino men often adopted gangster style, whether or not they were in gangs. [In gay clubs in the 90s,] you would walk in and see this sea of mostly bald heads, like gangster drag. They were as perfectly starched and as creased down, as any gangster on the street. It was an interesting and curious crossover, taking on the style of a group that would never tolerate you openly.”

Whereas most of the exhibition is focused on a historical perspective, Mario Ybarra Jr’s section looks to a speculative future. He recruited eight younger artists to contribute work that offers a glimpse of the next generation. These range from Alonso Garzon’s handmade post-apocalyptic outfits, to Michael Tafoya’s ballpoint prison-style drawings, and Yvette Mayorga’s painting Chola, which depicts a ghostly Virgin Mary figure surrounded by pop art-inspired images of products you might find at a typical Mexican corner store, merging the sacred and the profane. Ybarra Jr has designed a futuristic Plexiglas exhibition structure to guide visitors’ experience. “I feel like I’ve gone from painter to pointer,” he joked.

Although Tastemakers aims to shed light on LA stories – in large part Latino – that have been overlooked, it has a resonance well beyond just a limited audience. “The show is in east LA, it comes from that perspective, but it’s also very rooted in the human condition,” says Ybarra Jr. “At the root of it all, it is about a rebelliousness, and a hope to resist.”

Tastemakers & Earthshakers: Notes from Los Angeles Youth Culture, 1943 – 2016 opens on Saturday at the Vincent Price Art Museum

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion