Rory Staunton: The boy who died from a gym class scrape

12-year-old Rory Staunton's tragic death from sepsis sparked an international movement to raise awareness of the little-known condition

Rory Staunton

At 5ft 9in, 12-year-old Rory Staunton was the tallest child in his class in Queens, his freckled face and auburn hair a nod to his Irish heritage. Like other kids, he was obsessed with aeroplanes, 'Family Guy', his skateboard, his bike and Gaelic football.

Rory, the son of Mayo-born immigration lobbyist and businessman Ciaran Staunton, and his Louth wife Orlaith, was also an idealist who admired the civil rights activists Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King. He aspired to enter politics, like his uncle Fergus O'Dowd, a former junior minister, and his idol John F Kennedy.

In 2011, he shook hands with Barack and Michelle Obama during a family visit to the White House on St Patrick's Day. Rory should now be 17 and debating America's presidential race. Instead, he lies buried beside his grandmother in Orlaith's hometown of Drogheda. On one dark April day in 2012, Rory's life was needlessly cut short by an entirely preventable condition called sepsis. His body was flown back to Ireland, a one-way trip to a final resting place in the cradle of his extended family.

"Every memory of Rory is a fond memory," Orlaith says from the New York home she and Ciaran share with Rory's young sister Kathleen. "There are none we don't treasure, from moments we laughed to arguments over homework or a wet towel in his room."

Plenty of 12-year-old boys come home with scratches or grazes from falling off a bike or from the rough and tumble of a sport. So the Stauntons didn't initially pay much heed to the two plasters on Rory's arm when he arrived home from school on March 28, 2012. He had fallen while diving for the ball during a basketball game, and Rory's gym teacher had applied the plasters to the seemingly innocuous cut. Four days later, Rory was dead.

Ciaran says: "Rory had fallen onto the gym floor, and we found out later that there had been an outbreak of strep A in the school."

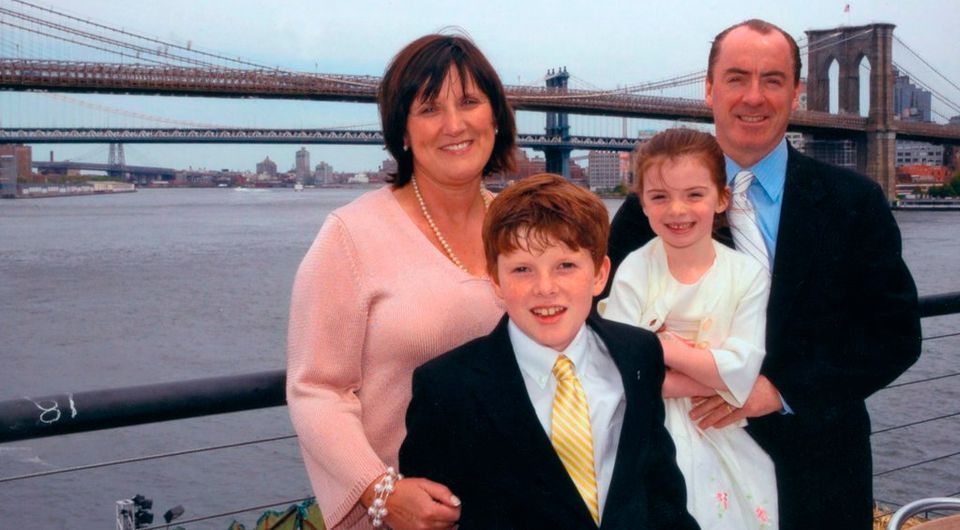

Day out: Orlaith and Ciaran Staunton with their children Rory and Kathleen, pictured in 2008

Unbeknownst to his parents, Rory was already beginning to suffer from sepsis, a life-threatening condition triggered when the body's immune system goes into overdrive to fight an infection. The condition went undiagnosed and untreated because the family paediatrician and emergency room physicians failed to recognise the symptoms - until it was too late.

"My beautiful red-haired boy was almost black all over his body when he died," Ciaran says.

Rory Staunton

Sepsis is the largest killer of children in the world, but most parents, including Ciaran and Orlaith, had never heard of it.

"We were worried about meningitis," Ciaran says.

At midnight on the day of his fall, Rory woke up complaining about a pain in his leg and started vomiting. His parents coaxed him back to sleep, but, the following morning, his temperature was high. They immediately called his paediatrician, who agreed to see him at 6pm that day, a Thursday. While she took his vital signs, noted his elbow scrape, mottled skin, stomach tenderness and pain in his leg, she concluded that Rory was just suffering from a stomach bug that was making its way around New York, the Stauntons claim. She advised the couple to take Rory to the hospital for an intravenous drip and to let the virus run its course.

At the emergency department of a New York hospital, doctors sought to rehydrate Rory with two bags of IV fluids, sent blood samples off to be tested, prescribed him an anti-nausea drug, and then sent him home. By Friday morning, Rory's parents were struggling to control their son's pain and his fever of 40˚C. They yet again relayed their concerns to his paediatrician. They brought him back to hospital that evening, where he was admitted to the intensive care unit and diagnosed with septic shock. He died that Sunday evening.

The distraught Stauntons later discovered that the emergency department blood tests, which indicated a very high white blood cell count, were not viewed by the doctor who ordered them that Thursday. Crucially, there was no system in place to communicate the test results to the doctors treating Rory or to his parents.

While sepsis is often referred to as blood poisoning or septicaemia, these terms specifically refer to the invasion of bacteria into the bloodstream. But sepsis is the body's extreme response to any kind of infection. Without prompt treatment, sepsis can lead to multiple organ failure and death.

Indeed, it was revealed last week that Lucinda Smith, a 43-year-old mother of two and solicitor from Essex, died from sepsis three days after scratching the back of her hand while she was gardening after being misdiagnosed by her GP, who suggested she had a trapped nerve and prescribed her anti-depressants to relax her.

Sepsis kills more people a year than breast cancer, prostate cancer and HIV/Aids combined. In Ireland, where it is the number one cause of death in hospitals, more than 10,000 patients were diagnosed with the condition in 2015, with an average mortality rate of 20.4pc, according to Dr Vida Hamilton, the HSE's national clinical lead for sepsis and a consultant in anaesthesia and intensive care at University Hospital Waterford.

Compounding the issue is the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in outpatient care, which has led to a dramatic increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Despite their grief, the Stauntons vowed that no other family would have to endure such a devastating loss. They launched the Rory Staunton Foundation for Sepsis Prevention to raise awareness of the condition that killed their son, and ensure there is a speedy diagnosis and immediate medical treatment for others with the illness.

Ciaran, a lobbyist for the undocumented Irish in America, says: "Who will be the last child to die from sepsis? We wished it was Rory."

In 2013, the foundation initiated the first US Senate hearing on sepsis. It also led to the introduction of Rory's Regulations, a set of protocols adopted as law in the state of New York that requires hospitals and other healthcare facilities to enact best practice for the early identification and treatment of sepsis. Under the new regulation, all hospitals in the state are compelled to communicate critical test results in plain language to parents before a child is discharged.

Ireland has embraced the campaign and become a leader in the fight against sepsis. In 2014, Leo Varadkar, the former minister for health, launched the HSE's clinical guidelines for healthcare staff on how to recognise and treat sepsis.

These guidelines, adapted from the 2012 Surviving Sepsis campaign, were recommended by the Health Information and Quality Authority (Hiqa) following Savita Halappanavar's death from sepsis in 2012. Quarterly national audits are now underway to examine how hospitals are complying with these guidelines, according to Deirdre O'Brien, a consultant microbiologist at Mercy University Hospital in Cork.

"A key message of this guideline is Sepsis 6 - six key interventions which must be given within one hour of a patient diagnosed with sepsis. These six interventions are broken down simply into 'giving three' (antibiotics, fluids and oxygen) and 'taking three' (blood cultures, measuring the urine output of the patient, and checking the patient's bloods for signs of infection)."

On Wednesday, Ciaran Staunton will address a conference on sepsis that O'Brien and the Mercy Foundation was instrumental in setting up for the members of the South/South West hospital group. At the conference, which will be held at Cork University Hospital, healthcare professionals will share their experiences and learn from national and international experts about how they can better manage sepsis.

Last month, the Rory Staunton Foundation began a public awareness campaign called Know the Signs of Sepsis. It involves a series of videos where parents of sepsis victims share the final words of their children. In a video shared more than half a million times on Facebook, Orlaith recalls how the last words Rory spoke to her were: "Mom, my toes are cold, my toes are cold".

She says: "Not knowing any better, I thought it was because they weren't covered by a blanket and I rubbed his toes and covered them. They were cold because the blood had stopped flowing to them - this is what happens in septic shock, the blood does not flow where it should flow; it stops flowing to the vital organs, causing them to fail, and then, most often, your loved one dies. We had no idea."

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news