Jura drifts off mainland Argyll in a sea littered with small islands and skerries. From the ferry, it appears to be near-empty. “There is nothing”, is how people describe the place – an expression of either appreciation or horror. The writer Kathleen Jamie called it “fabulous nothing”.

Only slightly smaller than the Isle of Wight, which has a population of 133,000, Jura has fewer than 200 inhabitants. The island has been associated for decades with the Astor family, scions of the fabulously wealthy American Waldorf dynasty, and in particular with the former Observer newspaper editor, David Astor. David Cameron visits his father-in-law’s estate for family holidays, a reminder of the persistence of Anglo-Scottish privilege among the British elite.

For a century, Jura has been an anomaly: remote, but under 100 miles from Glasgow or Edinburgh; sparsely populated, yet associated with periodic influxes of the powerful, wealthy and glamorous in search of space and privacy. Appropriately, one of the most bizarre artistic statements about wealth was made on Jura in 1994, when the two members of the pop group the KLF filmed themselves burning £1m in banknotes in a disused boathouse at Ardfin.

George Orwell heard of Jura from Astor, his editor, who regaled him with stories of its beauty and fishing – irresistible to the enthusiastic angler. Orwell, chafing at the restrictions and privations of wartime London, wrote in his diary in 1940 that he was “thinking always of my island in the Hebrides”. He had to wait until 1946 to make the journey, and it turned out to be a melancholy pilgrimage in the aftermath of the deaths of his mother, wife and a sister within the space of three years. But he was enraptured: “These islands are one of the most beautiful parts of the British Isles and largely uninhabited.” He added: “Of course it rains all the time but if one takes that for granted, it doesn’t seem to matter.”

Britain’s understanding of itself – its identity and its place in the world – is deeply rooted in being an island. Yet Great Britain is not an island; it is made up of at least 5,000 islands, around 130 of which are inhabited. But this geographical reality has often been ignored, because island, in the singular, brings with it the attractive characteristics of inviolability, steadfastness and detachment. As one clergyman put it in a sermon praising the Act of Union with Scotland of 1707: “We are fenced in with a wall which knows no master but God only.”

Even more erroneously, England is sometimes described as an island. Martin Amis wrote a television essay on England in 2014, which began with images of waves pounding chalk cliffs and the quintessential English mistake: “England is an island nation.” England in fact shares its island with other nations – Scotland and Wales – yet the language of sharing, of being part of an archipelago, has not featured in the English nation’s self-image.

British culture has a long-standing love affair with islands. In Utopia, Thomas More wrote how King Utopos created an island from an isthmus by digging a channel 15 miles wide. Britain’s detachment from continental Europe brought a degree of protection from invasion, and was seen as God’s geographical blessing for a chosen, favoured people. Shakespeare bequeathed a trove of vivid images of England in John of Gaunt’s speech in Richard II: “This little world”; “This blessed plot”. But there has also been an English ambivalence about islands; in a comparably famous passage, John Donne warned of the dangers of separation in his Meditation XVII: “No man is an island, entire of itself, every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.”

In the 18th century, after the Act of Union, the island theme became a unionist project for reform and progress. Daniel Defoe, a unionist, entitled his 1724–27 three-volume book of journeys A Tour Thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain, a title which made clear its political commitment to the island now made whole. In Defoe’s descriptions, Britain was a place of energetic activity, reordered for building, farming and hunting; it was to be “improved”, a term which became deeply political in Scotland. He developed this theme in his novel Robinson Crusoe, in which the tropical island was “virgin land” to be tamed and harnessed in order to make it productive. Crusoe made tools, farmed and built a fortified estate with a town house and a country retreat in a story of ceaseless industry. He also prayed and read his Bible. Crusoe established dominance over the island’s one inhabitant, Friday, who became his servant. It was a manifesto for empire, and articulated a model of Protestant Christian piety which owed something to the New Testament teaching to be “in the world but not of the world”. The island, set apart, both expressed and offered spiritual advantages.

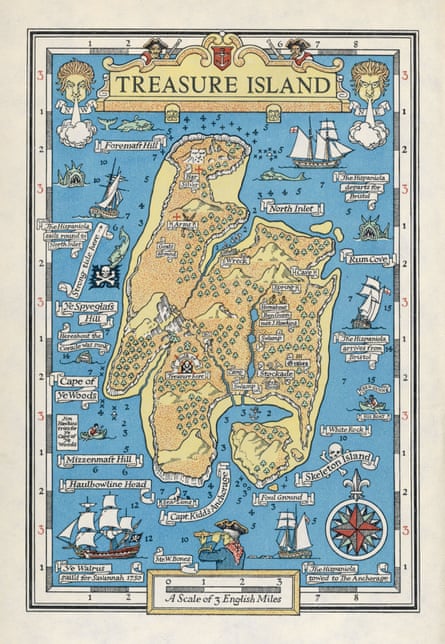

In British literature, islands emerge as places of particular power. They offer magic, intrigue and adventure as well as damnation. Treasure Island, Peter Pan, Swallows and Amazons and Lord of the Flies are all set on islands. It is significant that the authors of three of them – JM Barrie, Arthur Ransome and Robert Louis Stevenson – spent formative periods in the Hebrides. Stevenson based Treasure Island on the small island of Erraid off south-west Mull.

Some island-lovers want to do more than visit; they want to live out their own Robinson Crusoe dream. Throughout the 19th century, mansions and grand estates were built in the Hebrides. But the plutocrats who built them soon discovered that they had subjected themselves to the uncertainties of the west coast climate. While they had mastered much of the natural world, they were still at the mercy of the winds and the tides when it came to getting or leaving home.

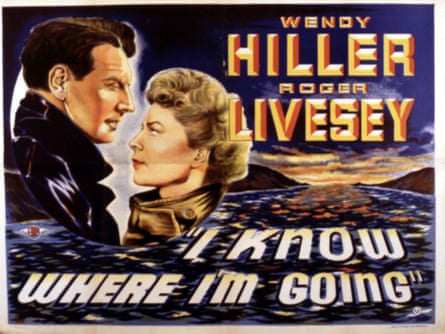

The intermittent accessibility of islands is central to the plot of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s I Know Where I’m Going! (1945). The glamorous heroine, a Londoner, heads to a Hebridean island to be married to her fiance, but gets stranded by heavy storms on the mainland, where she falls in love with a penniless sailor. Islands can throw you off course; they are places of the unexpected, and that is part of their appeal. This is particularly true of the Hebrides. They disrupt the best laid plans, sabotage the most cherished fantasies and offer the most startling – and seductive – surprises. They demand pragmatism and cheerful adaptability of their inhabitants. Islands don’t lend themselves to grand plans and big theories – the weather is too fickle.

Islands can provoke a volatile emotional intensity. This was the subject of a haunting novella by DH Lawrence, The Man Who Loved Islands, said to have been inspired by the writer Compton Mackenzie, an islophile and Scottish nationalist. Mackenzie, whose work includes Whisky Galore, set on a fictional Hebridean island, lived on a succession of islands – Capri as well as Herm and Jethou in the Channel Islands – before moving to Barra in the Outer Hebrides in 1928. Lawrence’s novella, set in the damp mists and gales of unspecified islands, is a cautionary tale of the seductive dangers of islomania. Over the course of adventures on three islands, the hero invests – and loses – a fortune in creating his “little world”, then becomes increasingly unstable before he finally loses his mind and retreats alone to a rocky outcrop. Islands prove the ruin of him.

Mackenzie piqued Orwell’s interest in the Hebrides before Astor encouraged him to go to Jura. Along with close associates such as the poet Hugh MacDiarmid, Mackenzie helped establish the Hebrides as a place of refuge, solace, even salvation, for a civilisation in crisis in the middle of the 20th century. During those decades of war and depression, fault lines were emerging in Britain’s identity. The Hebrides offered an artist a vantage point, suggested Mackenzie; near enough to still feel part of home, but far enough away to salvage some perspective in a terrible half-century of violence.

He was one of a number of writers who left London in the 1920s. Lawrence Durrell went to Corfu; DH Lawrence to New Mexico and Italy; Basil Bunting to Tenerife; Aldous Huxley to California. Such was the exodus that, in 1936, Durrell wrote home asking: “Is there no one writing at all in England now?”

There were some practical reasons for writers to flee the metropolis in search of cheap rents on ramshackle but spacious houses. The discomforts of leaking roofs, draughty cottages and having to gather one’s own fuel and water became an accepted part of the creative experience.

Orwell rented Barnhill on Jura in 1946, and it was there that he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. Here, he found the clarity of vision for a piece of fiction that captured the politics of the postwar world. He had the critical distance not just to see his own times clearly, but to divine in them the threat they posed to human freedom.

It was a perspective only possible from an island, only imaginable in such remote isolation. Jura was everything that was threatened in Nineteen Eighty-Four; it offered an abundance of wild natural beauty, and required a visceral physicality of its inhabitants. Orwell understood these qualities to be among the precious constituents of human freedom. Only in their midst could he imagine such a grim and vivid vision of oppression.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion