- India

- International

At the Last Count

An exhibition at DAG Modern discusses the formation and disbandment of Group 1890, and the individual art practice of its members.

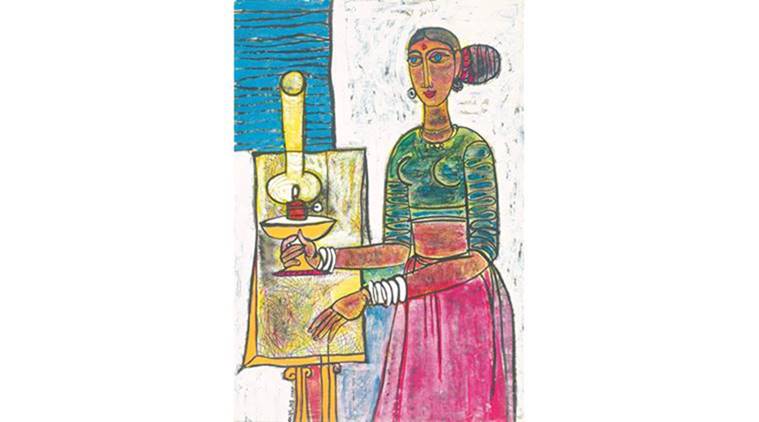

A work by Jyoti Bhatt

A work by Jyoti Bhatt

The India of the ’60s was a rather precarious nation-state struggling to find its feet after the 1962 Sino-Indian war. While the country struggled to overcome a bruised economy, the field of art had its own struggles. Several of the Mumbai Progressives had departed to the West to discover their unique language in art, and others in India were on a lookout to find ideologically like-minded practitioners, with whom they could unite under a single umbrella. It was during the period of such uncertainty that Group 1890 was formed.

Unlike most other groups of the era — including the Progressive Artists Group, the Bengal Group and the Cholamandal Artists Group — this was not confined within geographical borders, neither did its members share a similar oeuvre. Though it could not sustain for long, with just one exhibition of its members, months after it was born in 1962, it remains significant even 50 years after its inception.

“It created something significant, a body of work under each individual artist that had merit and its own identity,” says Kishore Singh, Head, Exhibitions and Publications, DAG Modern.

The curator has put together an exhibition that traces the evolution of each of the 12 members that comprised the group. Up at DAG Modern, Hauz Khas, the display ascertains the conviction that though their celebrated consolidation failed, individually each artist made a lasting impact.

The introduction is made through a Kishor Parekh photograph. In the winter of 1962, standing in the Qutub Minar premises are Jeram Patel, Himmat Shah, Jyoti Bhatt, J Swaminathan, Rajesh Mehra, Raghav Kaneria, Balkrishan Patel, Ambadas, Gulammohammed Sheikh and SG Nikam. Eric Bowen and Reddappa Naidu are absent, but they were in cognizance of the manifesto, initially drafted by J Swaminathan, who was the chief driving force behind the group. While a copy of it is reproduced in a publication accompanying the exhibition at the gallery, Singh notes how the manifesto was exceptional in putting the image as sacrosanct.

The name of the group was derived from the address of art collectors Jayant and Jyoti Pandya’s Bhavnagar (Gujarat) home, where the artists met. A document issued stated the group’s “goal”, which was “to launch a fearlessly critical and resolute movement for unleashing truly creative energies, to open genuine vistas of expression”. If Patel was to popularise blowtorch on burntwood, Shah was reckoned for his terracotta and clay works. Jyoti Bhatt documented the folk and tribal arts of Saurashtra in his photographs, accompanied by Kaneria. Swaminathan’s work introspected the miniature and neo-tantric tradition, and Sheikh turned to figurative narratives reflecting varied contemporary issues. While Bowen and Ambadas were to continue their practice in Scandinavia, Mehra came to be known as one of the finest art teachers at College of Art, Delhi, and Naidu drifted to the Cholamandalam Artists Group. Nikam and Patel, meanwhile, faded into oblivion.

The group managed to get Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to inaugurate its first and sole exhibition in 1963 at AIFACS in Delhi. The exhibition opened to much critical acclaim, but none of the works on display found buyers. While the catalogue did not feature images of any of the works being exhibited, Singh has scanned through the reviews and interviews to locate them. In his curatorial exhibition, he has successfully traced the evolution of the artists since.

Though several factors are said to have contributed to the dismemberment of the group — including “disinterest” of Jeram Patel and interspersing of its members — art critic Prayag Shukla notes that “the narrative of them stayed together”. It served a crucial purpose too. As Sheikh notes, “It was a crucial moment in the shaping of our work and ideas… the presence of 1890 remained deeply embedded in our psyche because it not only enabled us to unleash the unknown reserves of energy but also became instrumental in opening up multiple avenues of explorations, both in your work and ideas.”

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05