- India

- International

How Tamil Nadu’s rural industry model can keep farm unrest at bay

Decentralised industrialisation, entrepreneurship from below have been absent in states that have seen recent unrest among agrarian communities.

While the majority of Kongu Nadu farmers may still be Gounders, the majority of Gounders are no longer farmers.

While the majority of Kongu Nadu farmers may still be Gounders, the majority of Gounders are no longer farmers.

“The soil here is very saline with electrical conductivity value of 9. We can grow only chloride-loving crops like coconut and the MR-2 variety of mulberry.” That was Tamil Selvi, recently telling this correspondent about the 5.75-acre land farmed by her father Natarajan Gounder at Velayuthagoundanpudur, a small village around 25 km from Pollachi, famous for its cattle and jaggery markets, and 55 km from Tirupur, better known as India’s Knitwear Capital.

While Natarajan hasn’t studied beyond Class 4, Selvi is doing an MSc in agronomy from the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University in Coimbatore, and his younger daughter, Gomathy, is in the final year of her BSc in mathematics at Pollachi’s NGM College.

Selvi knows all about the 300 coconut trees on 3.5 acres, the silk cocoons spun by larvae fed on leaves from the mulberry plants on 1.5 acres, and the green fodder in the remaining land for the family’s six cows. She wouldn’t mind taking up her father’s occupation, but not immediately. “I am keeping my options open,” she said.

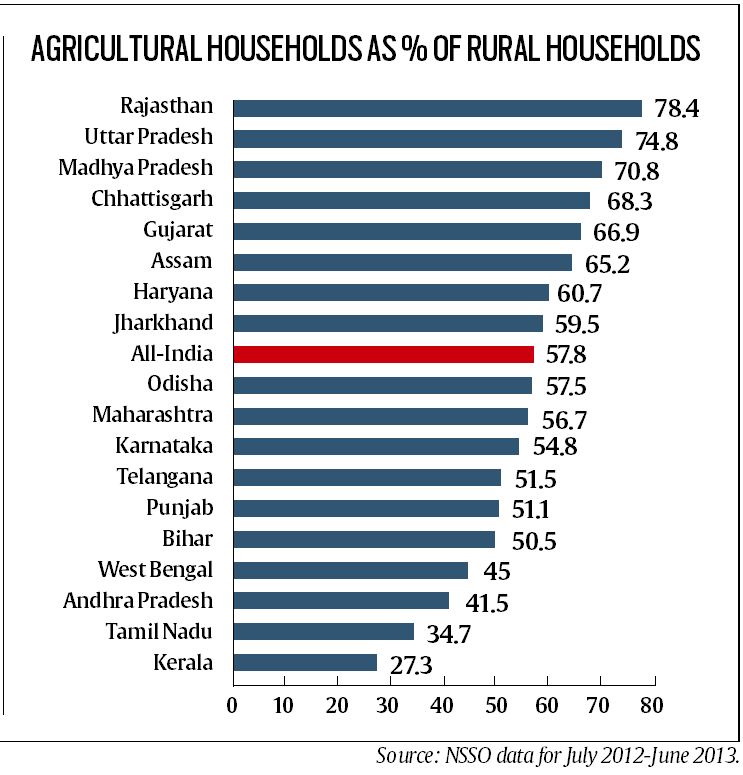

Keeping options open is something that agricultural communities like the Kongu Vellalars, or simply Gounders, of western Tamil Nadu (TN) have been able to exercise much better than their counterparts elsewhere — for whom farming is more a compulsion than choice. This has been made possible mainly by decentralised industrialisation. Gujarat, Maharashtra and TN are three states where manufacturing’s share in the GDP is higher than every other sector, including agriculture. The difference, however, is that manufacturing activity is much more spread out and decentralised in TN. This is reflected in National Sample Survey data, showing only 34.7% of rural households in TN to be engaged in agriculture, as against 56.7% in Maharashtra, 66.9% in Gujarat, and 57.8% for India as a whole.

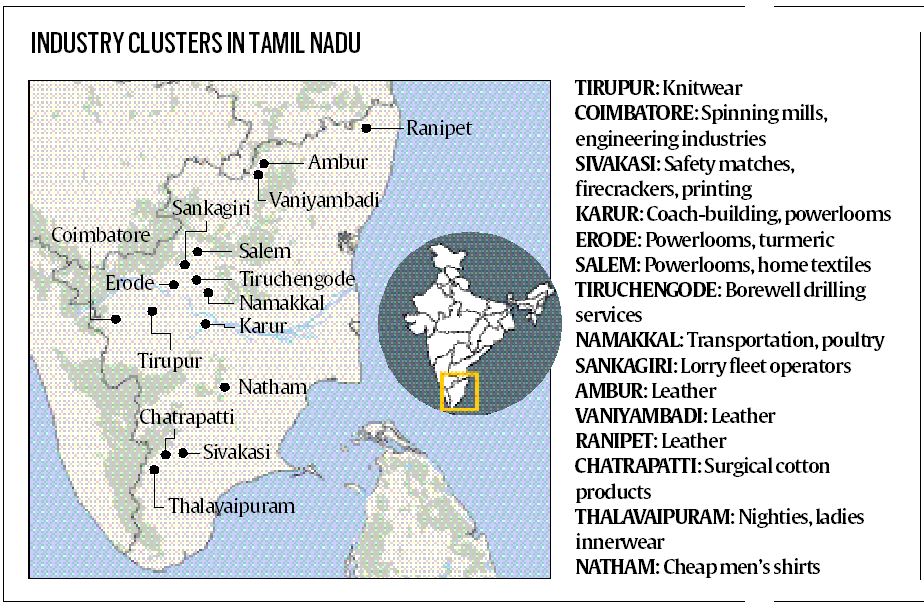

Decentralised industrialisation, in turn, has to do with the development of clusters. In TN, they have come up closer to rural areas, helping integrate the countryside with the town, and create real diversification options outside of agriculture for the likes of Tamil Selvi and Gomathy. Some of these clusters are familiar names: Sivakasi for safety matches, firecrackers and printing; Karur, Erode and Salem for powerlooms and home textiles; Tirupur for knitted garments. In many cases, they have been built by farming communities themselves via investment of agricultural surpluses.

The pioneers of Coimbatore’s spinning mills and engineering industry — spanning products from castings, textile machinery and auto components to pumpsets and wet grinders — were Kammavar Naidus. Tirupur’s knitwear units, which generated export revenues of over Rs 23,000 crore in 2015-16, are mostly owned by Gounders. Members of this peasant caste entered the sector from the late-1970s, investing in secondhand circular knitting machines and stitching power tables to supply hosiery products to Mumbai- or Kolkata-based exporters. Over time, they leveraged their control over the entire subcontracting network — wherein the finished garment makers down to the layers of job-workers were largely Gounders — to emerge as direct exporters. Many went on to promote spinning mills, mainly in districts adjoining Coimbatore — Dindigul, Tirupur and Erode.

Gounder penetration is not restricted to textiles. The bus body fabricators of Karur, borewell drilling services contactors of Tiruchengode (they take their truck-mounted rigs even to Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh) and lorry fleet/bulk cargo logistics operators of Namakkal and Sankagiri too are predominantly from this community. Some of these towns are clusters for more than one industry. Thus, Namakkal is a transportation as well as egg-laying poultry farm hub, Erode is a powerloom and “turmeric city”, and Karur has both powerlooms and coach-building concerns.

It would be a mistake, though, to assume that cluster-based rural industrialisation in TN is a phenomenon confined to the western ‘Gounder belt’, also referred to as Kongu Nadu. There is enough documentation of the leather clusters of Ambur, Vaniyambadi and Ranipet in the northern district of Vellore. Some of the less written-about clusters are closer to or even south of Madurai. We need mention just a few. Chatrapatti, near Rajapalayam, is a major manufacturing centre for surgical cotton products like bandages, gauze pads/rolls/swabs and other woven dressings. Thalavaipuram in Tirunelveli district has become a production hub for nighties and ladies innerwear. Natham, about 35 km from Madurai, is home to a number of garmenting units specialising in low-priced men’s formal shirts.

Three points are worth noting here. First, all the clusters conform to the concept of ‘industrial districts’, which the late-19th century economist Alfred Marshall described as “the concentration of specialised industries in particular localities”. Such agglomerations of small and medium-sized enterprises derive comparative advantage from people within the neighbourhood imbibing shared knowledge “as it were in the air”.

Second, these clusters have sprung up in small urban centres, providing employment avenues to people in surrounding villages who would otherwise have had to migrate to big cities for work

Third, the promoters of the clusters are small capitalists, typically from ordinary peasant stock and provincial mercantile castes such as the Nadars of Sivakasi and Virudhunagar, as opposed to big MNC or pan-Indian Bania-Marwari capital.

Such decentralised industrialisation and entrepreneurship from below has been relatively absent in the states that have witnessed unrest among agrarian communities: Jats in Haryana, Marathas in Maharashtra, Kapus in Andhra Pradesh and Vokkaligas in the Mysuru belt. The rural countryside in these parts has remained overwhelmingly agricultural. That may have been fine so long as farming was reasonably remunerative — which was the case in the post-Green Revolution phase until the 1980s, or even in the more recent 2004-13 period coinciding with a global agri-commodity price boom.

But the last two years or more have seen the perfect storm from subdivision and fragmentation of landholdings, coupled with back-to-back droughts and price crashes in most crops, hitting farming households badly. The effects have been particularly felt in regions where rural youth have few options outside of agriculture — and economic activity linked to industrialisation is concentrated in select pockets, be it Mumbai-Pune, Bengaluru-Hyderabad or Delhi-Gurgaon.

Not surprisingly, the spontaneous street protests now — peaceful or otherwise — have come from dominant castes tethered to the farm and unable to exploit the opportunities thrown up by globalisation and urbanisation. Their experience has been different from that of the Gounders: While the majority of Kongu Nadu farmers may still be Gounders, the majority of Gounders are no longer farmers.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05